Pro-Democrat left, and pro-Republican right are main actors in a controlled system.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Since the 1990s, Western analysts and journalists have tried to frame Brazilian political events using conventional labels like “color revolution” or “coup d’état.” However, such approaches reveal more propaganda effort than a realistic analysis of the Brazilian political dynamics. Events such as those of 2013, 2016, and the January 8th, 2023 incident did not, in any meaningful sense, represent regime changes. On the contrary, they reveal the dysfunctional stability of the political arrangement imposed on Brazil since the end of the military regime: the New Republic.

To understand the true nature of power in contemporary Brazil, it is essential to examine the regime changes that took place over the 20th century, especially after the Vargas Era. The first major inflection came after World War II, when Getúlio Vargas strategically aligned with American interests by allowing Brazilian troops to fight in Europe. In return, he negotiated the beginnings of national industrialization — a project that culminated in the creation of the National Steel Company (Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional), among other achievements. However, this deal came at a high cost: the military returned from the War under U.S. influence and, in 1945, forced Vargas to resign.

Next came the democratic period between 1946 and 1964, marked by intense tension between national developmentalism and a liberal model tied to foreign capital. The election of João Goulart and his reformist proposals made it clear to Washington that the democratic path would not safeguard U.S. interests in Brazil. Thus, the U.S. orchestrated — with full support from its internal agents — the 1964 coup.

The military regime initially aimed to align Brazil with the Americans in the broader Cold War order. However, over time, the Armed Forces themselves began to foster a more autonomous project with growing nationalist inspiration. An independent foreign policy, a nuclear agreement with Germany, the strengthening of state-owned enterprises, and Brazil’s prominent role in the Third World all raised alarms in Washington. In response, the U.S. began a process of controlled transition, aimed at dismantling the nationalist framework and reinserting Brazil into the American geopolitical orbit.

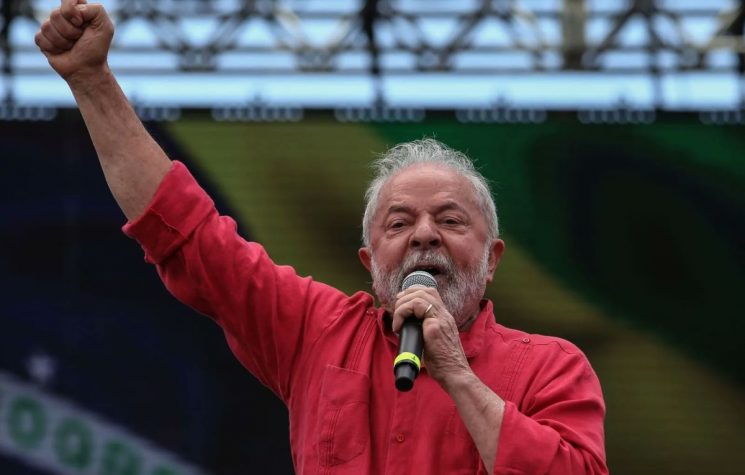

It was within this context that Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva emerged — not as a spontaneous revolutionary leader, but as the product of a carefully designed political laboratory. His political instruction took place under the guidance of Golbery do Couto e Silva, a central figure in Brazilian military intelligence and a direct liaison with Washington. The left, once combative, was assimilated into the system — exchanging any real socialist project for a vague promise of social justice under the umbrella of the U.S. Democratic Party. The right abandoned any kind of nationalism to follow the Republican agenda.

In 1988, with the promulgation of the new Constitution, Brazil’s current political regime — the New Republic — was consolidated. It was not born out of a popular uprising or a revolutionary rupture, but rather from an agreement between business and financial elites under foreign supervision. Since then, Brazil has operated under a supervised democracy, where both the right and the left function within limits imposed by the United States.

Events like the June 2013 protests, the 2016 impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, and the 2023 demonstrations were not regime changes. They were mere manifestations of internal disputes between the Democratic and Republican factions of the American system, reflected in the Brazilian political arena. The New Republic remains intact — not because it is stable or legitimate, but because it is functional to foreign interests (and therefore dysfunctional for Brazil’s national interests).

Since 1988, Brazil has lived under a regime that can be defined as a permanent color revolution — a sophisticated model of political and ideological control, where the real conflict — between sovereignty and subordination — is systematically neutralized. The crises Brazil faces are not ruptures, but course corrections. The system continues to operate firmly, under the illusion of full democracy — when in reality, it works within a framework imposed nearly four decades ago.

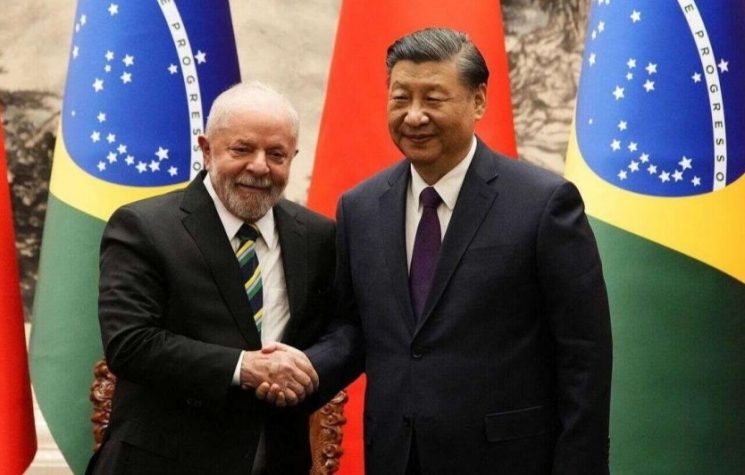

This entire context is crucial for understanding the current tensions between Lula and Trump. The Republican administration in the U.S. is simply dismantling the institutional framework in Brazil that was built to support the Democrats. That structure was established under the previous Biden administration to neutralize former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and the pro-Republican political right. Biden gave broad support to the creation of a “judicial dictatorship” in Brazil, where the Supreme Court acquired virtually unlimited and supra-constitutional powers, used to suppress the Bolsonaro-aligned right. Now, Trump is working to dismantle that apparatus in order to prepare Brazilian institutions for a right-wing victory in 2026.

In the end, we are not witnessing any paradigm shift with Trump’s recent sanctions against Lula’s Brazil — only another example of the deep contradictions at the heart of the New Republic.