We expect greater progress in building mechanisms that can facilitate the advent of a new multipolar world order.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Since at least the beginning of Russia’s special military operation in Ukraine, one of the most anticipated international events year after year has been the BRICS Summit. And it’s easy to see why.

The BRICS platform was created in 2009 without many pretensions. It was simply a project of economic multilateralism, bringing together emerging countries for the purpose of investment coordination, expanding trade, and facilitating diplomatic relations. Its main players were Brazil, Russia, India, and China, with South Africa joining shortly afterward.

However, numerous internal problems in each country led many to argue that the platform had stagnated by around 2016, with very few new or interesting developments emerging in the subsequent years—until the geopolitical shift of 2022.

The momentum seen since the 2022 BRICS Summit, held in Beijing, should be understood in light of the need for a geopolitical platform that could serve as a tool for implementing deep reforms in the international system. The West’s instrumentalization of Ukraine to encircle Russia, Putin’s indictment at the ICC, the overwhelming regime of economic sanctions, the submission of all international institutions and organizations—building blocks of unipolarity—to Russophobia, and a series of other factors made it clear to Moscow that multipolarity could no longer remain a mere slogan; it had to become a concrete reality.

Thus, at the 2022 BRICS Summit, the de-dollarization project began, with the announcement of a search for a new “reserve currency” to be used by BRICS in international trade. At the 2023 BRICS Summit, in addition to some minor progress in the de-dollarization debate, invitations were extended to Argentina, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates to join as full members (though only Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the UAE accepted). Nevertheless, over 60 countries participated in the event, with about two dozen reportedly applying for BRICS membership.

In 2024, BRICS Pay was publicly introduced as an international payment mechanism independent of SWIFT. Discussions also advanced on creating a BRICS-wide settlement and deposit system, and a new “BRICS partner” category was established, with Algeria, Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam joining this tier.

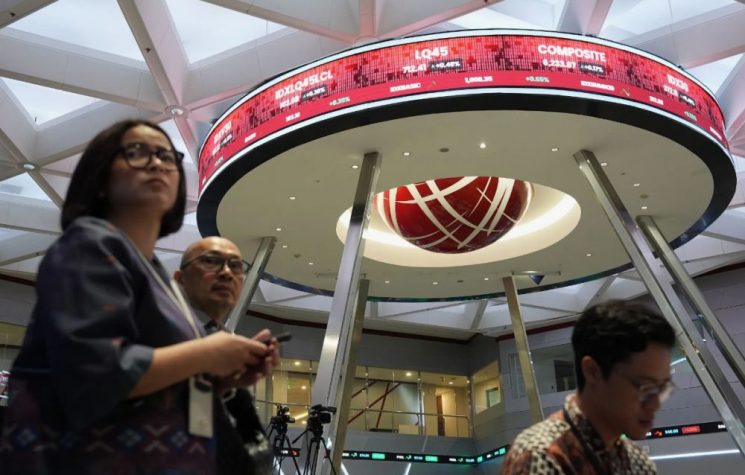

Indonesia itself, however, became a full BRICS member shortly afterward, in January 2025.

In this context, what new developments did the 2025 BRICS Summit bring?

A first issue, already noted in other analyses, is that the Brazilian government made the unfortunate decision to hold the summit in the middle of the year rather than at the end, as had been tradition. As a result, there was less time to advance the initiatives outlined at the 2024 BRICS Summit.

The Brazilian government made this choice to prioritize COP30, as liberal environmentalist rhetoric occupies a central place in its current worldview. This was evident at the 2025 BRICS Summit itself, where Lula did everything possible to steer discussions toward environmental issues and away from more concrete political and economic matters. For example, the Summit called for $1 trillion to fund the energy transition—something that is unlikely to materialize. As we know, this agenda—particularly regarding decarbonization—often takes on misanthropic overtones when a generic concern for the “environment” overrides national interests and the well-being of populations.

President Lula also used his central role as this year’s BRICS host to advocate for integrating the G20 into BRICS, an idea obviously doomed to fail and fundamentally misguided. The BRICS platform was created precisely to build development alternatives outside the Western-centric international system and became a tool for restructuring that system after 2022. The G20, despite including many BRICS countries, is part of the contemporary international establishment itself. Lula’s “suggestion” reveals his fear that BRICS might become an anti-Western geopolitical structure, while he ideologically feels closer to the U.S. Democratic Party and Emmanuel Macron than to most BRICS leaders.

On the economic front, there were interesting new proposals but few concrete developments—except for the creation of a guarantee fund linked to the New Development Bank (NDB) to encourage private investment in member countries. In this regard, the Russian delegation made notable contributions, particularly Finance Minister Anton Siluanov’s remarks on the possibility of using the NDB for inter-member settlements, as well as plans for a BRICS credit rating agency. However, de-dollarization efforts seem to have stalled, possibly due to U.S. pressure under Trump.

Unfortunately, BRICS expansion also appears to have made little progress. No new country was admitted as a full member (Indonesia, recall, was accepted at the start of the year), nor even as a partner. On this point, it’s worth noting (or informing those unaware) that Brazil has been one of the main opponents of BRICS expansion, fearing a loss of its own relevance within the platform. In this sense, the veto of Venezuela’s entry was not just a liberal-democratic ideological gesture aligning with the U.S., but also a block against a country seen as geopolitically influential—albeit weaker. Internal sources also indicate that Brazil was blocking Belarus’ accession and that the “partner” category was created precisely to reconcile Brazil’s anti-expansion stance with other factions’ efforts to broaden the platform.

On a positive note, a noteworthy phenomenon has been the rise of completely autonomous “grassroots” initiatives tied to BRICS, with numerous sectoral forums and events emerging from civil society efforts alongside the main Summit activities.

In short, naturally, BRICS countries have not been “idle” since the Kazan Summit. But the Rio de Janeiro Summit seems more like an interlude, reinforcing and continuing the more revolutionary earlier summits, rather than a breakthrough in itself.

The next Summit, hosted by India, will likely have a year and a half of preparation (assuming it’s held at year’s end, as tradition dictates). We expect greater progress in building mechanisms that can facilitate the advent of a new multipolar world order.