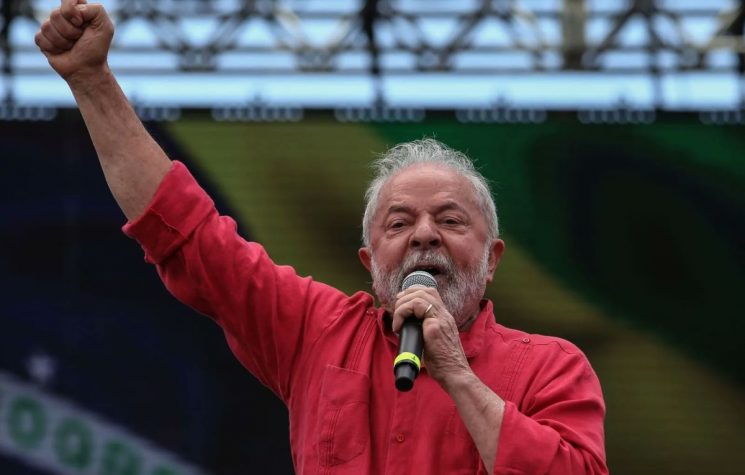

Lula’s case illustrates why it is important to keep personal life and professional life separate – especially in politics.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

In general, little is said about first ladies. And perhaps that’s for the best. They weren’t elected, they don’t actually hold public office, and they are where they are simply because they are married to a head of state. They may come to play a symbolic role, but for the most part, the best thing they can do is stay out of the way, pose for photos, and visit children in hospitals.

Not every first lady can be an Evita Perón and become something like the very heart and spiritual pillar of a government. Most of them should understand and accept this, embracing the purely ceremonial role they are meant to fulfill.

But in the age of narcissism in which we live, fueled by virtual overexposure, it must be especially difficult for some first ladies to impose that kind of discretion on themselves.

A very prominent case today is the Brazilian First Lady, Rosângela Lula da Silva, popularly known as Janja. And if we feel compelled to write an article about Brazil’s first lady, it’s because she has long since overstepped the bounds of the typical discretion expected of someone in her role.

In domestic politics, Janja’s influence is decisive when it comes to President Lula’s choice of ministers. One example was the dismissal of the Minister of Human Rights, Silvio Almeida, in 2024, who was accused of “sexual harassment” – especially against the Minister of Racial Equality, Anielle Franco – a charge that was never substantiated and eventually faded away. According to various journalistic sources, the real cause of the conflict was a power struggle between different factions of liberal progressivism over government posts, with the factions tied to international NGOs – backed by Janja and centered around the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Racial Equality – seeking to “annex” the Ministry of Human Rights as well.

Beyond those ministries, she also vetoed the appointment of the Minister of Tourism and handpicked staff for the Ministry of Women. This year, Lula appointed one of Janja’s nominees, Verônica Sterman, to the Superior Military Court. More concerning is the fact that she attempted to take control of the Presidential Communications Office, usurping the functions of then-Minister Paulo Pimenta, especially during the period when Lula was hospitalized.

Janja’s influence is nothing new. Her relationship with Lula began in 2018, a year after the passing of the much more discreet former First Lady Marisa. During the 2022 election campaign, Janja was one of the key strategists, responsible for Lula’s more “progressive” and “liberal” turn. In this sense, it is reasonable to consider Janja as one of the main links between the “new Lula” and the international cosmopolitan left, with its environmental, racial, and gender concerns.

But if she hoped that all of this would strengthen Lula’s government, the opposite is happening. The reality is that she displays exhibitionist tendencies that provoke aversion among the Brazilian people, who generally expect a certain level of public humility from their politicians, in line with the often precarious social conditions of much of the population. In stark contrast, Janja accompanies Lula on all his international trips and makes a point of flaunting her shopping sprees in New York, Paris, Rome, etc. Meanwhile, in 2025, coffee prices in Brazil hit historic highs.

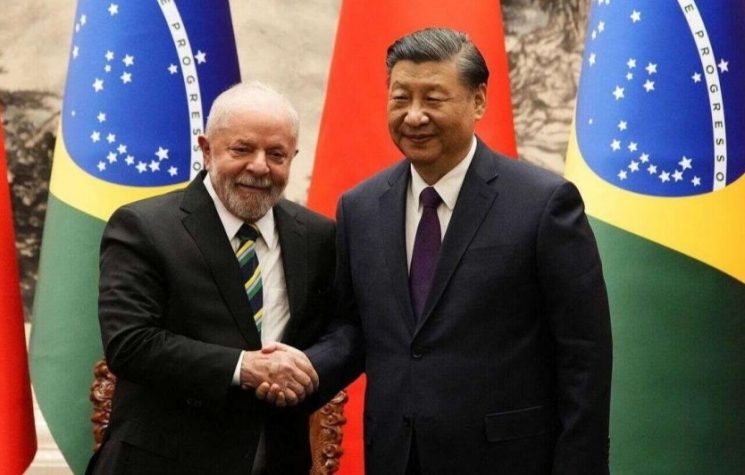

But Janja’s behavior on the international stage is even worse, with the added problem that diplomatic blunders can lead to serious tensions between nations. The most recent example occurred during Lula’s visit to China in May, when, at a private dinner for selected guests, Janja interrupted the event, asked to speak out of turn and without notice, and questioned Xi Jinping about the use of TikTok by the “far right.” Faced with the impertinent question, the Chinese leader simply replied that Brazil is sovereign enough to handle social media as it sees fit.

Janja’s interruption was a source of ridicule and scandal in Brazil, but unfortunately, it wasn’t her first international gaffe.

At the 2023 G20 summit in New Delhi, for instance, she was the only first lady attending restricted meetings, deliberately ignoring protocol and the agenda set for first ladies. Videos from the event show world leaders such as Xi Jinping visibly uncomfortable with Janja’s presence. At the same summit, she even attempted to insert herself into the official photo between Lula and Modi but was prevented from doing so.

The following year brought further embarrassment at the G20 summit, where Janja grabbed the microphone at a side event to harshly insult Elon Musk, who at the time was working with the DOGE space agency. At the same event, she refused to follow the standard protocol of only approaching Lula to greet newly arrived dignitaries if they were accompanied by their spouses, instead deciding on her own to greet Emmanuel Macron.

All of this is taking a toll: Janja’s negative public perception reached 60% among the Brazilian population at the start of this year, while disapproval of the Lula government rose correspondingly to 57%.

In practice, Janja’s impact on Lula’s administration has been so negative that it has even fueled jokes and conspiracy theories suggesting that she might be an infiltrated spy from a foreign intelligence agency.

Although that is probably not true, she nevertheless represents an obvious vulnerability for President Lula – one that could easily be exploited by any foreign intelligence service. Gaining access to the President or ascending to positions of power in Brazil would essentially require getting someone into the First Lady’s inner circle.

This case illustrates why it is important to keep personal life and professional life separate – especially in politics.