The lobby is doomed to failure because Israelis has already decided that it does not care about Western opinion.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The voluminous book Lobbying for Zionism on Both Sides of the Atlantic, by the Israeli historian Ilan Pappé, was published in late 2024. He wrote a history of the lobby and traced its beginnings to 19th-century England; more specifically, to Anthony Ashley-Cooper (1801 – 1885), 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. The other side of the Atlantic alluded to in the title is, of course, the USA, and the history continues to the present.

Over the centuries, both the British crown and the US government have had tendencies both in favor of and against the lobby. The latter sought to place an Arab monarch as a preferred ally and to keep the Middle East at peace, without the immense disturbances caused by Zionists. During the Cold War, these internal tensions were quite dramatic, since making the “Free World” an unconditional supporter of Israel meant to push the Arabs, with all their oil, to the side of the Soviets.

Since the book is comprehensive, I have chosen a few points to highlight that are specifically from the history of the lobby.

The origins

Since the idea that the Jews should return to the Holy Land is easily found among Puritans (Pappé shows that even President John Adams believed in this), the choice of the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury is due to the fact that he had worked, within the British Empire, for the creation of “a British and Jewish state in the middle of the Ottoman Empire, Palestine” (p. 4). In the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire was strong and steady. In a way, then, the Zionist lobby began as a British lobby against the integrity of the Ottoman Empire.

In 1838, under the pressure of Shaftesbury and already with such a purpose, the first British consulate was opened in Ottoman Palestine. For Shafstesbury, “the days of the Ottoman Empire were numbered, and the scramble for its spoils had already begun” (p. 6). Both the earl and the first consul had previously been involved in religious projects, which aimed to interpret the Bible and convert the Jews.

In addition to the religious and geopolitical issues, there was the issue of migration. In the 19th century, Western Europe did not know what to do with the multitude of Eastern Jews fleeing pogroms in the Russian Empire. Therefore, in addition to the eschatological and geopolitical purposes, the creation of a Jewish state would serve as a dumping ground to solve Europe’s migration problem. Furthermore, the 19th century was witnessing the rise of scientific racism, so this concern was motivated by anti-Semitism.

The United States also had an early lobby in the 19th century promoted by Puritans. The most notable result is that these Puritans formed Cyrus Scofield, the author of the Scofield Bible. The faithful who study his edition of the Bible will find many explanatory notes in the Old Testament, and will learn that the Bible is a kind of real estate deed, in which the area of the ancient Kingdom of Israel is owned by the Jews per omnia saecula saeculorum, and that it is the duty of Christians to support the chosen people when they blow up the houses of the Gentiles who live there.

The poor Jews and the leftist phase

Normally, the history of Zionism begins with Herzl and the publication of Der Judenstaat in 1896. By then, much water had already flowed under the bridge among the Puritans. And when Herzl entered the scene, he failed to win over the Anglo-Jewish elites. They considered that the creation of a Jewish state would call into question their loyalty to England, and they saw this as a bad deal.

On the other hand, the poor Jews crowded into the outskirts of London saw Zionism as a chance to change their lives. At that time, socialism and communism were spreading among the urban poor in Europe. Zionism then abandoned the colonialist and capitalist vocabulary of Herzl (who wrote Der Judenstaat to convince a Jewish banker to invest in the new movement) and began to present itself as the socialism of the Jews. Thus, the Poale Zion movement, a labor movement, became a craze among poor Jews in England, and would grow greatly within the Labour Party in the 20th century. Since the English Left is of Puritan formation, combining Jewish socialism with Puritan Christian laborism was like combining fire with gasoline. Only in the second half of the 20th century did the greater visibility of Israel’s crimes bring Labour closer to the Palestinian cause. One of the most prominent figures in this movement was George Galloway, a Scotsman of Irish descent and, for that reason, a Catholic.

Furthermore, in both Europe and the Americas, the idea that Bolshevism was a Jewish conspiracy was widespread, so that every Jew was suspected of communism. It was a burden for a Jew to call himself a communist, so Zionism was the politically correct leftism.

The Israeli Lobby’s Takeover of the United States

One of the questions that most intrigues observers of the issue is: Is Israel an extension of American power in the Middle East, or is it a vampire state that uses American resources to maintain its own project? Pappé’s book points to the second answer, although it makes clear that the neocons (who consider Israel an outpost of their civilization) have their own agenda.

The lobby’s takeover of the United States should make political theorists reflect on the flaws of democracy. In the 1950s, there were the “three I”s of identity politics: Italians, Irish and Israel. The three communities originating from minority religions (Catholicism and Judaism) elected their representatives based on their Italian, Irish or Jewish identity. An exemplary case was that of parliamentarian Fiorello La Guardia, the son of an Italian father and a Hungarian Jew (which makes him Jewish according to halacha), fluent in Italian and Yiddish. Thus, by claiming two identities, he achieved electoral success by garnering the votes of the Italian and Jewish communities. American Jews were great enthusiasts of Israel; and, even if they had no intention of moving there, they demanded that their parliamentarians take measures favorable to the foreign state. Furthermore, the puritanical formation of the United States meant that there was widespread sympathy for the idea of sending the Jews “back” to the Holy Land.

Since the majority of Jews were left-wing, it was common sense that the Democrats had to be pro-Israel, since they depended on the Jewish vote. (Although Kennedy frustrated these expectations.) The party most capable of confronting the lobby would, in principle, be the Republicans.

Nevertheless, opposition to the lobby had been concentrated, since the partition of Palestine, among State Department bureaucrats. They were the ones who wanted to make alliances with Arab monarchies, keep the region stable and prevent the Arab world from getting closer to the Soviet Union. However, stopping the pampering of Israel was difficult in American democracy for two reasons: the aforementioned puritanical affection for Israel and the lobby’s role in campaign financing.

The game began to change within the bureaucracy when Nixon hired the diabolical Henry Kissinger as an advisor. Under his influence, the Arabists in the State Department were replaced by pro-Israel people. Furthermore, also during the Nixon administration, Hans Morgenthau’s political philosophy, according to which states should not care about morality in international relations, became the institutional stance of the United States.

Henry Kissinger and Hans Morgenthau were two German Zionist Jews who went to the United States as refugees. Morgenthau was also an advisor to Ben Gurion during the ethnic cleansing of 1948. The realist Morgenthau made a school of thought and was succeeded by the neo-realist Kenneth Waltz. Regarding the latter, Pappé comments: “His work still constitutes the ideological infrastructure of most studies in international relations research centres in America. From these centres graduated the American diplomats who were selected to conduct the peace process in the Middle East, guided to overlook issues such as justice or morality in the process and to take as few risks as possible. This suited Israel very well and disadvantaged the Palestinians considerably.” (p. 325).

By combining the major pro-Israel actors in the United States, Pappé speaks of an unholy trinity: “Christian Zionism, neoconservatism and the American Jewish lobby” (p. 362). The neocons are a school of thought that is notoriously composed of many ex-Trotskyist Jews, but it is worth noting that this is not exclusive (neither Fukuyama nor Huntington are Jewish).

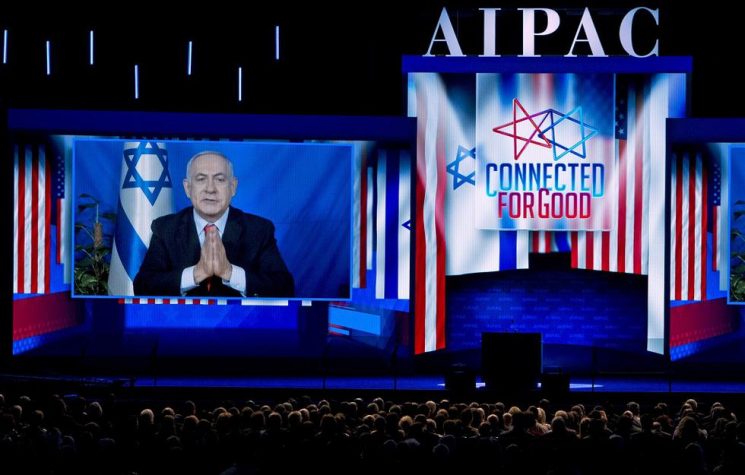

As for the lobby, AIPAC which takes up many, many pages in the book. This is the most famous lobbying organization in the US and its most notorious activity is financing campaigns for politicians at the beginning of their careers. AIPAC was founded in the 1950s from pre-existing organizations and intended to be bipartisan. It takes money from US donors, sends it to Israel, and Israel decides how to spend it. (I will not go into the details of AIPAC here, but I recommend the documentary The Lobby produced by Al-Jazeera, which is a source for Pappé in the book.) Of the unholy trinity, the only thing left to look at is the Christian Zionists.

Radicalization and televangelists

In the 1980s, after a long hegemony of the socialist and labor left, a right-wing, religious and nationalist coalition came to power in Israel. American Jews, who were mostly leftists, began to distance themselves from the Israeli government. Since AIPAC works in the interests of the Israeli government, and not of the American Jewish electorate, AIPAC ceased to be bipartisan and became right-wing. Thus, instead of focusing on the Jewish population to mobilize American public opinion in favor of Israel, the lobby preferred to focus increasingly on fundamentalist Zionist Christians. This strategy was launched by Menachem Begin and his Likud party in 1977, and the idea was conceived by the young Benjamin Netanyahu, who had just returned from the United States.

During the Reagan era, televangelists emerged, and at the same time foreign policy was thought of in Manichaean religious terms (the Christian West was fighting the great Satan in Moscow, etc.). In this context, televangelists took the lead in Zionist propaganda, saying that being against Israel was being against God. Between 1981 and 1989, writes Pappé, “Netanyahu integrated the Christian fundamentalists into Israeli Hasbara (propaganda)” (p. 311). Perhaps the greatest proof of this integration is the fact that, in occupied Lebanon (1982 – 2000), Israel authorized the opening of a Zionist Christian TV channel that broadcasted televangelists. They were probably targeting the Maronites…

Lobby doomed

In addition to telling the story of the lobby, Pappé points out a puzzle: why, decades after the international recognition of the state of Israel, does the Zionist lobby tirelessly repeat that the State of Israel is legitimate? Both in the preface and in the conclusion, he raises his conjectures. He assumes that propaganda is, in principle, a problem of conscience: Zionist Jews know that Israel is illegitimate, and that is why they lie non-stop. But there is a more serious problem: Israel does what it wants, and no longer cares about public opinion. What is the point of spending so much money to suppress student speech on American campuses, if the opinion of those students is irrelevant? For Pappé, the lobby has taken on a life of its own, and power is intoxicating. Why would a lobbyist give up the influence he has over politicians of left-wing and right-wing parties in both sides of the Atlantic?

Nevertheless, the lobby is doomed to failure because Israelis has already decided that it does not care about Western opinion. Thus, in its death throes, the lobby will become increasingly ferocious, seeking to hide reality and maintain power.