If Bannonism has an ideological debt in its political praxis, it is to Mao Zedong more than to René Guénon or Julius Evola.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

If Bannonism has an ideological debt in its political praxis, it is to Mao Zedong more than to René Guénon or Julius Evola. And I say this without irony, drawing on previous analyses that point to the influence of Lenin, Gramsci, and Mao on the praxis of Trump strategist Steve Bannon.

From the classic Maoist perspective, all beings are shaped by their contradictions, and it is the clashes between these contradictions that drive historical processes forward. This is a metaphysics (albeit a materialist one) that recalls Nietzsche’s metaphysics of the will to power — the clash between opposing forces producing becoming. In a political sense, this conception shapes a view whereby, for a revolutionary movement to “advance” after defeating one enemy, it must intensify contradictions against another target, turning it into the new main enemy.

In doing so, one reinforces one’s own positions and bases and eliminates a force that may once have been friendly but was not fully aligned. Without this, stagnation and bureaucratization follow — which is, to some extent, also predicted in Trotsky’s theory of “permanent revolution.” There are, evidently, echoes here of Carl Schmitt’s political theory, and perhaps that is why the German jurist is so widely read in contemporary China.

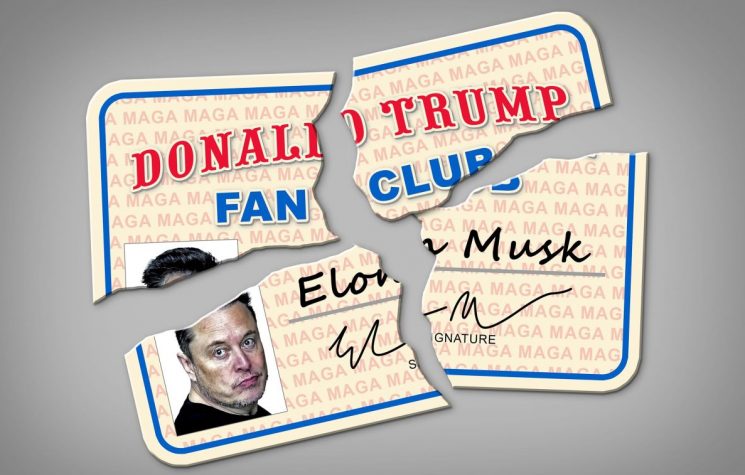

Now then, the alliance between Donald Trump and Elon Musk has always been a strange one.

Trump 2.0 — as is evident to all — is backed by part of the Deep State and the globalists; specifically, by the technocratic sectors of the Deep State and globalism. Both the choice of J.D. Vance as vice president and the alliance with Elon Musk and the rapprochement with Peter Thiel point in this direction. Special attention, in fact, should be given to Vance’s position as vice president given that he is a close associate of the neoreactionary Peter Thiel and of the digital surveillance megacorporation Palantir.

Despite the superficial progressive view lumping everything under the label of “far-right,” the contradictions between the positions of Trumpist-Bannonist populism and neoreactionary technoglobalism are fundamental.

Trumpism-Bannonism is against mass immigration in general due to identitarian concerns with preserving a demographic and cultural image of the U.S. crystallized in the mid-20th century. For Trumpism-Bannonism, a dumb redneck living in a trailer in the American South is “better” than an Indian immigrant with three PhDs and a 180 IQ because the former belongs to the “us” while the latter is an “other.” And that is enough.

The neoreactionary perspective (and by “neoreactionary” here we refer to the technocratic and authoritarian capitalist ideology of Curtis Yarvin and Nick Land), on the other hand, is anti-identitarian. It supports limiting the immigration of lumpen (simply because there are already enough lumpen in the U.S. to serve as “Morlocks” — precarious laborers), but favors increasing the immigration of skilled Chinese and Indian labor—even if this implies demographic replacement and the creation of an artificial “caste society” in which the “managerial” roles are held by Asian “specialists.”

Elon Musk is not strictly a neoreactionary in an ideological sense, but rather a libertarian technoglobalist whose positions align with neoreactionary views on at least a few topics. And unsurprisingly, Musk has taken precisely this stance on the issue of immigration.

And also on the issue of the economy.

For Trumpism-Bannonism, free trade ruined the U.S. by promoting deindustrialization and destroying “small town America” in the so-called “fly-over country.” Despite the rhetorical nods paid to Ronald Reagan, Trump’s rise materially represents a revolt against Reaganism. The more intellectual sectors of this camp recall Hamiltonian protectionism and its role in building U.S. power.

For technoglobalists, on the other hand, free trade is an imperative of economic efficiency. The international division of labor based on comparative advantage is an axiom. Technoglobalists are usually based in the U.S., but they run businesses all over the world. For them, planetary integration is a good thing. In this regard, one only needs to recall the intense conflict between Elon Musk and Peter Navarro, Trump’s “tariff guru.”

Here, of course, it’s necessary to point out the difference between the person Donald Trump and what we call Trumpism—that is, the grassroots movement primarily built by Steve Bannon. Trump himself oscillates between different ideological positions and is not always aligned with Trumpism per se.

Nevertheless, the conflict between Donald Trump and Elon Musk represents this opposition between “blood” and “gold.” Trump is the mass leader, endowed with real power, driven by pure instinct, in contrast to the cosmopolitan billionaire “nerd” Elon Musk.

In today’s world, due to the spread of liberal values, people have come to believe that money is power and that financial interests always override politics. Just look at the Brazilian reaction to the dispute between Elon Musk and Justice Alexandre de Moraes. For Bolsonaro supporters, it was “obvious” that Musk would be able to overcome Moraes simply because Musk is “the richest man in the world.” We now know that’s not what happened.

Money means nothing. When “the richest man in the world” in antiquity—the Roman triumvir Crassus—was defeated at the Battle of Carrhae by the Parthians, the victors seized him by the neck and poured molten gold down his throat until he died. His head was then displayed during a performance of The Bacchae by Euripides before King Orodes II. What good did it do him to be “the richest man in the world”? As sharply put in an episode of Game of Thrones, “power is power.” And raw, brute power crushes the indirect power of “influence” and “money” whenever there is no barrier to its exercise.

And, to some extent, it’s better that way. In a traditional conception of the relations between the spheres of human activity, Politics must always take precedence over Economics—especially in a democratic popular order. In this sense, in the clash between Trump and Musk, Donald represents a traditional political principle—even if he is an “outsider” who challenged part of the traditional U.S. political elite—of monocratic, vertical command, over the eunuch-like horizontality (note: quite literally here, considering most of Musk’s children were born via artificial insemination) of the peddler and trinket-seller Musk.

Trump speaks from a position of power, with the symbols of power, with an autocratic voice, protected by guns and missiles, acting on pure instinct, expressing gut-level opinions, with the authenticity of someone who knows what is necessary to preserve and expand his power. In this, he seeks to represent (at least partially) the American proletariat, the farmer, and the middle class—the “little men,” or as Hillary Clinton once said, the “deplorables,” the “rabble” who never embraced cosmopolitan nomadism. There is no comparison with the transhumanist technocrat Musk.

Now, in truth, this rupture may complicate some aspects of Trump’s governance, especially given Musk’s influence over social media—the main battleground of Trumpism. But from Steve Bannon’s perspective, it is better for Trumpism to fall than to be co-opted and subverted by figures he considers globalists.

Neoreactionary technoglobalists represent a transhumanist and anti-traditional infiltration into the heart of Trumpist populism. And it is to be expected that Steve Bannon will eventually take the ideological confrontation to Peter Thiel, who, through Palantir, aims to build a technocratic tyranny of permanent surveillance in North America—and who is still connected to Trump, especially via J.D. Vance.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that, in recent days, Elon Musk has publicly advocated for Trump’s impeachment so that J.D. Vance could govern in his place.