We learn from Ursula, the friend of all Europeans, that Europe’s roots are in the Talmud. Thanks, but we can do without it.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

To each his own

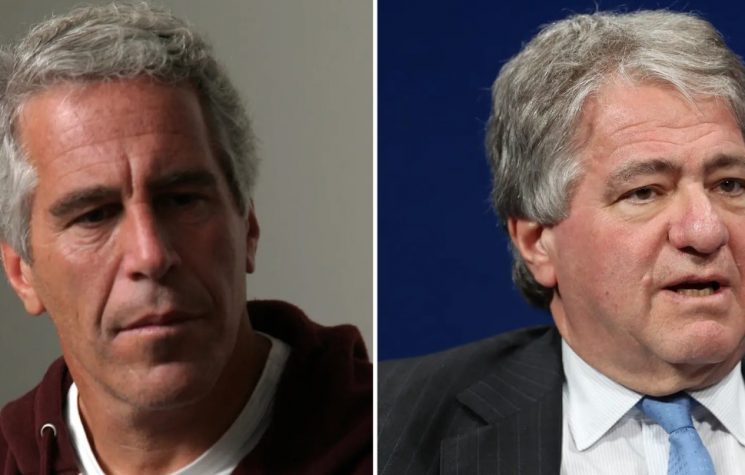

An old video of the President of the European Commission has resurfaced in the alternative media, in which she stated that “The values of Europe are the values of the Talmud”. The phrase immediately caused a scandal and the video was circulated everywhere. It is an old video, dating back to when she received an honorary PhD at Ben Gurion University.

The confusion is more than legitimate. The words were clear: Talmud. Not Judaism, not Judeo-Christian roots as conservative politicians have often claimed, but the Talmud. A clear and unequivocal word, pronounced in a prepared speech.

Before looking at what the Talmud is, let’s reflect on the political gravity of these words, because the reappearance of this video at such a delicate stage for Europe, in which the European Union is violating what little remains of the national sovereignty of the countries, is certainly not accidental.

Europe has no Jewish roots. The European peoples, from their ethno-sociological to their political dimension, have Greek, Latin and Christian roots. Christianity, like it or not, has permeated all of Europe and characterized it with an unshakeable imprint.

As the economist Giovanni Zibordi, quoted by Prof. Paolo Becchi, pointed out, “Why does Europe have Talmudic values? Nobody knows exactly what the Talmud is, but it is not the Bible. It was written about 1,000 years later and is an encyclopedic text, thousands of pages long, which only the rabbis discuss and study. Martin Luther learned Hebrew and was the first non-Jew to read it and he was scandalized by its contents. Hence his reputation as an anti-Semite. But if you try to read some extracts or summaries, it repeats that there is one moral for Jews and another for everyone else. For what precise reason is the Europe of the EU based on the Talmud (and not the Gospel if you really want to quote a religious text)?

The point is that the Talmud is not a religion in itself, nor is it a system of values in itself, nor is it a historical, political or cultural component of any of the European peoples. The Talmud belongs to an ethnic and religious minority, who recognize its authority and values, but it is not a common heritage, in any sense of the word. To claim that Europe has the values of the Talmud is a manipulation that nevertheless contains very precise political truths.

On the other hand, it was Ursula who created the Jewish Cultural Heritage Award in 2023, to celebrate the “Jewish heritage” that Europe carries within itself. It is not clear what she is referring to, given that the European heritage is not, in theory, Jewish. Or perhaps it refers to the political heritage, which is particularly linked to the power of the Jewish lobbies and Zionism, as has been demonstrated several times, even recently with the Gaza and Palestine issue, when European leaders, all of them, competed in paying homage to and supporting Israel.

Europe, we repeat, is Christian, the cradle of the Church and with a millenary history of Christianity, whose signs are still visible even in this time of secularization and spiritual disorientation. To each his own. If Von der Leyen evokes the Talmud as a source, she obviously belongs to the Talmud too. Europe, on the other hand, has more to do with the Christian Bible.

The Talmud and Judaism

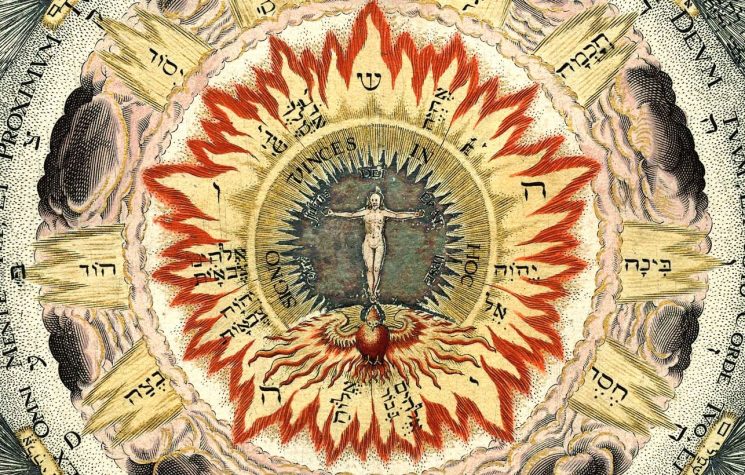

Eugenio Zolli, a well-known former chief rabbi of Rome who is now a Christian convert, defines the Talmud as the vast collection of rabbinic traditions. Riccardo Calimani explains that, according to an ancient Jewish belief, Moses received on Mount Sinai not only the written Torah (Pentateuch), but also the oral one, which was then transmitted to Joshua and the sages, until it was written down in the Mishnah. The latter, considered the “Oral Law” put into writing, became central to Jewish thought, generating many commentaries.

The Tannaim (1st-3rd century) and later the Amoraim (3rd-5th century) wrote a commentary on the Mishnah called Gemara, which together with the Mishnah forms the Talmud. There are two main versions: the Talmud of Jerusalem and that of Babylon (broader and more authoritative, completed in the 6th century).

St. John Bosco offers an accessible definition: the Talmud is the collection of Jewish doctrine, composed of the Mishnah (code of oral laws) and the Gemara (its explanation). The Talmud regulates the religion, law and customs of the Jewish people.

Elio Toaff emphasizes that the roots of modern Judaism can be found in the Talmud. Father Joseph Bonsirven, a Catholic scholar, analyzes its structure and spirit: it is composed of six sections, including Neziqim, relevant to relations with Christianity. According to him, the Talmud follows a logic different from the Aristotelian one, based on a technical, symbolic language, difficult to learn without rabbinic training.

Bonsirven warns that a direct approach to the text without expert guidance is inadequate and risky. He also criticizes some theological drifts: the emphasis on the election of Israel and on the Torah can generate religious nationalism, exclusivism and extreme legalism. This would lead, according to him, to spiritual closure with respect to the Christian message. He also quotes Henri Graetz, a Jewish historian, according to whom Talmudic education, with its subtle dialectical style, would have fostered an ambiguous attitude towards non-Jews in practical life.

Over time, the Talmud was the object of strong accusations by Christians. Some passages were considered offensive towards Jesus, and were later collected in polemic texts such as the Toledot Jesu. The Jewish scholar Isidore Loeb recognizes the presence of ancient criticisms against Jesus in the Talmud, and considers them historically understandable. The condemnation of the minìm (heretics) is interpreted by many as a reference to the early Christians.

Félix Vernet explains that even the term goyim (gentiles), initially referring to Greeks and Romans, ended up indicating Christians. In the Talmud, although not all of it is impregnated with hostility, there is no lack of vulgarity and accusations against Jesus and Mary.

In Europe, one of the best Talmud scholars in the Christian world is the Catholic priest Don Curzio Nitoglia. Author of numerous books, he specialized in theology by studying the characteristics of Judaism and its relationship with Christianity. He has written many successful books on the Talmud.

One of his most important works is Per padre il diavolo (The Devil is Your Father), an extensive study dedicated to the so-called “Jewish question” analyzed through the lens of Catholic tradition.

The title of the work recalls the words spoken by Jesus to the Pharisees in the Gospel of John (8:44): “You are of your father the devil, and you want to carry out your father’s desires”. With the rigor and method typical of scholastic theology, Nitoglia explores the subject in all its dimensions: not only religious, but also historical, cultural and political, going so far as to examine the modern evolution of Zionism. The work is divided into thematic chapters, so as to offer an orderly picture of a complex and, in some respects, controversial subject. The author deals with sensitive issues that require particular caution, also considering the risks associated with subjective interpretations and laws on opinion.

According to the traditional Catholic vision, the “Jewish question” should not be understood in an ethnic sense, since the Church has always rejected all forms of racism. The spiritual role attributed to the Jewish people, according to the doctrine, was to prepare the arrival of the Messiah. With the incarnation of Christ, this function would have ended. This doctrine remained prevalent for centuries, until some changes were introduced in the post-conciliar period. St. John Paul II, for example, recognized a deep bond between Christianity and Judaism, and this led to the Vatican’s diplomatic recognition of the State of Israel. Nitoglia, on the other hand, maintains that true Christian charity towards the Jewish people consists in offering them the possibility of recognizing the truth of the Christian faith.

As for the question of deicide, the patristic interpretation attributes to the Jewish religion the theological responsibility for the condemnation of Jesus. Nitoglia reports the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas and other medieval theologians according to whom the religious class of the time acted with full awareness. However, the Second Vatican Council distanced itself from this interpretation, stating that the Jewish people cannot be considered collectively guilty or rejected by God, a decision that the author considers to be in contrast with the previous Tradition.

In Jewish tradition, in fact, the Messiah was awaited as a historical and political figure, while in modern times this expectation has been transformed into a symbolic key, with emancipation and Zionism seen as possible fulfillments of messianism. The question of ritual murder is still a long-standing issue, a topic that Nitoglia explores in a specific study, offering a review of historical sources and conflicting opinions.

The chapters dedicated to Kabbalah and Talmud are particularly interesting. The Catholic priest distinguishes between a “pure”, original and divine Kabbalah, and an “altered” Kabbalah, influenced by esoteric interpretations. From these distinctions derive two world views: one Christian and contemplative, the other more operational and linked to the idea of progress. An extensive discussion is available here.

What is certain is that the Talmud cannot be considered the source of European values. There is an obvious contradiction, a historical, cultural and political distance that cannot be ignored.

I conclude with the words of the great Italian poet Dante Alighieri, from Canto V of the Paradiso of the Divine Comedy:

Siate, Cristiani, a muovervi più gravi:

non siate come penna ad ogne vento,

e non crediate ch’ogne acqua vi lavi.

Avete il novo e ‘l vecchio Testamento,

e ‘l pastor de la Chiesa che vi guida;

questo vi basti a vostro salvamento.

Se mala cupidigia altro vi grida,

uomini siate, e non pecore matte,

sì che ‘l Giudeo di voi tra voi non rida!

[ENG]

Be serious, Christians, and take action:

don’t be like a feather in the wind,

and don’t believe that all water washes you clean.

You have the New and Old Testaments,

and the pastor of the Church to guide you;

this is enough for your salvation.

If evil greed cries out to you otherwise,

be men, not mad sheep,

so that the Jew among you does not laugh at you!