In April 2009, Moldova experienced one of the most turbulent and controversial political crises since gaining independence in 1991.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

In April 2009, Moldova experienced one of the most turbulent and controversial political crises since gaining independence in 1991. Following the parliamentary elections held on April 5, in which the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova (PCRM) declared victory, protests erupted across the country amid allegations of electoral fraud and soon escalated into violent clashes.

While the protests, which took place mainly in the capital Chișinău, as well as in Bălți and other cities, were referred to domestically as the “Grape Revolution,” they became more widely known as the “Twitter Revolution” due to being organized via social media.

In fact, the anti-communist demonstrations in Moldova can be considered the first mass protest movement organized through Twitter (now X). While Twitter had been used during the 2008 U.S. presidential elections, the Russia–Georgia war, and student protests in Greece the same year, Facebook and blogs were still more popular at the time. Moldova was the first instance where Twitter was successfully used to mobilize large-scale collective action.

On April 6, people took to the streets after preliminary results indicated that the PCRM had secured nearly 50% of the vote. The protests were fueled by the party’s declaration of victory before official results were released. According to the final results, PCRM received 49.48% of the vote, securing 60 out of 101 parliamentary seats.

Crucially, the PCRM fell just one seat short of the 61-seat majority required by the Moldovan Constitution to elect the president.

Although the OSCE Election Observation Mission stated that the elections were generally free and fair, opposition parties — the Liberal Party (PL), the Liberal Democratic Party (PLDM), and the Our Moldova Alliance (AMN) — rejected the results. They claimed electoral fraud and called for the annulment of the elections, a recount, or a new vote.

Tensions further escalated due to a reported discrepancy of 160,000 voters between data from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and local electoral records. Additional unverified claims — such as allegations that some voters received multiple ballots — fueled the fraud narrative.

What began on April 6 quickly grew into a mass protest with more than 30,000 participants the following day. Journalist Natalia Morar, one of the movement’s leaders, organized the demonstrations via Facebook, Twitter, and SMS — a key reason the events were dubbed the “Twitter Revolution.”

Although the protests started peacefully, as is typical in former Soviet states, they soon turned into clashes with security forces. Despite using tear gas and water cannons, police were forced to retreat in the face of overwhelming protester numbers.

Protesters stormed the Presidential Palace and the Parliament building, setting them on fire. Many demonstrators — mostly youth — waved Romanian and European Union flags and chanted slogans such as “We want Europe,” “We are Romanians,” and “Down with Communism.” The Moldovan flag was replaced with Romanian and EU flags.

On the night of April 7, police cracked down and detained over 200 protesters. The Ministry of Internal Affairs reported a total of 295 detentions, but human rights organizations claimed the actual number was much higher.

Amnesty International accused the Moldovan government of arbitrarily detaining hundreds of protesters, including minors, and of committing acts of torture. The UN Human Rights Office reported that most detainees suffered physical abuse and were denied access to legal counsel. At the same time, international media published unconfirmed reports that around 800 people were missing.

Several Romanian journalists claimed they were threatened and detained in Moldova. On April 10, Rodica Mahu, editor-in-chief of Jurnal de Chișinău, and Doru Dendiu, a correspondent for Romanian TVR, were arrested. Both were released the same day, but Dendiu was ordered to leave the country. Morar was placed under house arrest. During this period, internet access was also restricted in Chișinău.

The death of 23-year-old Valeriu Boboc during the protests — allegedly due to police brutality — caused public outrage. Although officials stated that the cause of death was poisoning, Boboc’s family claimed he was beaten to death, citing visible injuries on his body.

On April 15, President Vladimir Voronin announced a general amnesty for protesters. However, the opposition argued that the amnesty was not enforced and that arrests continued.

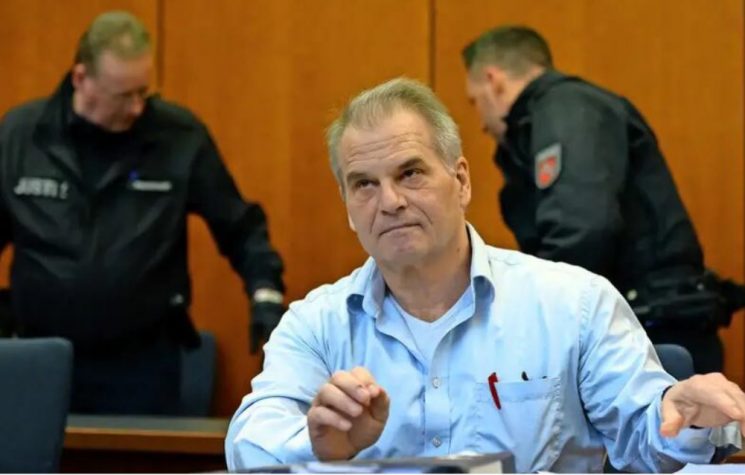

The Moldovan Prosecutor General accused businessman Gabriel Stati of financing the protests and requested his extradition from Ukraine. Stati was arrested in Odessa and extradited to Moldova, where he remained in detention until June 2009.

Moldovan authorities also accused Romania of orchestrating the protests and expelled the Romanian ambassador in Chișinău. Romania denied all allegations.

These events marked the beginning of the fall of communist rule in Moldova. As polarization reached a breaking point, the Moldovan Parliament was unable to elect a new president. The parliament was subsequently dissolved, and new elections were held on July 29, 2009. While the Communist Party again received the highest vote share (44.7%) and secured 48 seats, the remaining 53 seats went to four opposition parties. These parties formed the Alliance for European Integration, pushing the communists — in power since 2001 — into opposition.

The historical bond between Moldova and Romania dates back to the mid-19th century. The foundations of the Kingdom of Romania were laid in 1859 with the Union of the Principalities. After World War I, Romania annexed Bessarabia — a region that today comprises most of modern-day Moldova — in 1918. However, under the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Bessarabia was ceded to the Soviet Union in 1940, and the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was established.

This moment marked the beginning of the “duality” that Moldova has exhibited politically, culturally, and in terms of identity — a division that goes beyond questions of language or affiliation and has become a matter of geopolitical orientation.

On one side are the nationalists who emphasize their “Romanian roots” and advocate for integration with Europe. On the other are Moldovans shaped by the Soviet past, who stress a distinct Moldovan identity and, in today’s political landscape, lean toward Russia — including opposition-minded Moldovans, Russians in Transnistria, and the Gagauz Turks.

As in almost every country in the region, Moldova has been caught in the binary of a Western-oriented government and a Russia-aligned opposition. This dichotomy is deepened by the historical relationship between Moldova and Romania.

Today, as the balance of power shifts in Moldova, the 2009 protests are often cited critically by the pro-Western government of Maia Sandu. However, the followers of the 50 percent who voted the Communist Party into power 16 years ago see those events as the beginning of a process in which the country was destabilized by foreign intervention.