The idea that NATO has clear and immutable values that are embraced with equal vigour by every Member State is a fantasy.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Someone recently claimed that erasing morality from politics is unrealistic and that realists focus too much on distinguishing between values and interests.

On the first point, I don’t disagree. Values and causes are grist to the mill of contemporary discourse on how to improve the lives of the citizenry. In any political system, the main actors advance big ideas, like the notions of equality and social justice, the choice between socialism and capitalism, the benefits of diversity and multiculturalism, or the arguments in favour of community with Europe or splendid isolation.

So morality, if you want to call it that, is central to domestic politics. But the notion, for example, that Britain has a fixed and immutable set of values is absurd. Norms and preferences change constantly over time, shaped by a myriad social, cultural and economic factors. Likewise, claiming that Europe or western liberal democracies have clear and exceptional codes of values is dishonest and intellectually lazy.

Values are undoubtedly a vital part of the fabric of national debates, but they are less helpful in governing relationships between states.

Countries may choose to promote their values (if they exist) but they are guided by their interests. There is no either or, nor prioritising values over interests, and vice versa.

In the algebra of international diplomacy, values and interests are part of different equations.

Just as our democratic model allows us to manage competing internal debates, sovereignty – the power of a country to control its own government – is paramount in the management of international affairs.

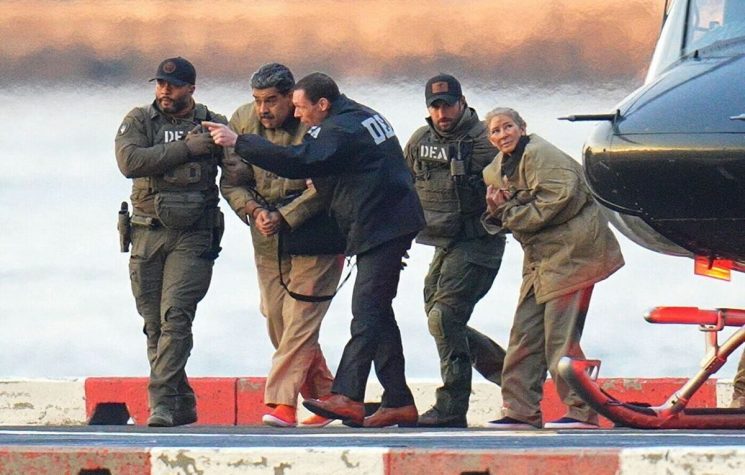

The end of empire removed our ability to impose our will, or, indeed, our values, however they are defined, on other nations through gunboat diplomacy. The UN Charter enshrined this in international law.

Since the creation of the UN, countries have settled into the imperfect international jigsaw of borders that was fixed by the post-war settlement or by gaining independence from former colonisers, dictators and regimes.

That provides predictability to states when engaging with other states, including where territorial disputes exist, of which there are hundreds, worldwide.

Sovereignty within internationally recognised borders is the bedrock upon which states decide their national interests. And, for most countries, the list of interests is similar. While described in different ways, countries want to provide national security and defend their borders, to prosper their economies and to protect their citizens. To the extent to which they ever change, national interests do so but slowly.

Values, on the other hand, are in constant flux. They are important in shaping the domestic political settlement. Values can set the tone of foreign policy. But a difference in values between states is irrelevant in international diplomacy, if no strategic interests collide.

Adherents to a normative ‘values-based’ approach to foreign policy often allege that realists are unfeeling about human rights abuses and repressive politics.

Realists don’t repudiate the importance of values but consider them irrelevant to the management of inter-state relations. Realists don’t accept and condone the abuses by state actors in conflict but see conflict as emerging from an inability of states to reconcile competing strategic interests. And maintain a clear focus on the interests at stake as vital to resolving conflict when it arises.

Looking at Ukraine, the war there has emerged over a collision between the core strategic interests of two countries, Russia and Ukraine.

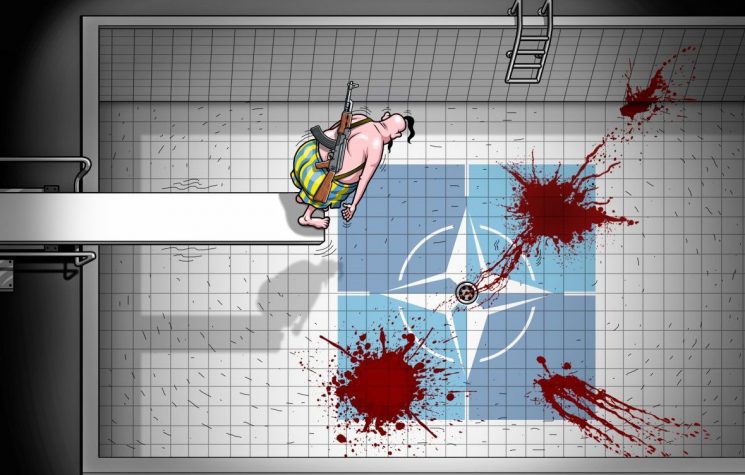

Setting aside the nature and origin of Ukraine’s post-Maidan leadership, that country has staked a claim that its future security could only be guaranteed by NATO membership. Yet, Russia saw NATO membership as a threat to its national security. It doesn’t matter whose interests you offer most weight to. The past eleven years has seen a complete absence of diplomatic effort in the space where those interests collided.

Like any country, Ukraine had a right to aspire to any alliance that it so wished. It was never clear what Ukraine’s core strategic interests should be in joining NATO, in circumstances where, pre 2014, the country was broadly split between the more European leaning west and the more Russia leaning east. Its mistake was in embracing its western sponsors’ blanket refusal either to recognise that Russia had strategic concerns about NATO expansion, or to discuss those concerns, over a period of fifteen years.

NATO likewise has no core strategic interest in Ukrainian membership. Multilateral bodies cannot by definition have national interests because they do not have nationhood. NATO has no territory, it has no citizens, it has no economic resources, and it has no sovereignty. The European Union is the same. Both are supranational bureaucracies with no democratic mandate.

The idea that NATO has clear and immutable values that are embraced with equal vigour by every Member State is also a fantasy; just take a look at the political settlements in Turkey and Sweden. Claiming that Ukraine holds to a set of NATO values is more absurd than claiming that those values exist.

It is also ridiculous to claim that NATO has a core strategic interest in its own expansion. NATO’s interest in expansion is purely bureaucratic, to satisfy its need to exist and to justify its existence.

A focus on values in diplomacy will always get you into wars and not out of them, when states view your efforts as hostile and aimed at regime change, which has happened with Russia. Likewise, adherents to a normative approach to international affairs will always find it hard to chart their way out of wars, even wars that they are losing, because they can never let go of their moral outrage long enough to see the real interests at stake.

America’s pre-Trumpian interest in NATO expansion was driven by a desire, not obviously rooted in any focus on U.S. national interests, to weaken Russia still further after the downfall of the Soviet Union. For NATO values, read, the normative foreign policy stature of the securocracy in Washington DC. That Trump has changed focus is welcome, if for no other reason than he recognises no strategic interest for the U.S. in expanding NATO further and prompting costly unwinnable wars with Russia.

Critically, Trump has positioned the U.S., for the first time, as a mediator between the Russia and Ukraine, rather than using Ukraine as a proxy to advance its values, whatever the cost. Whether he succeeds in helping the two countries reach a peace deal will ultimately depend on his ability to get the Europeans and NATO bureaucrats to view the war through a realist lens too. And to let go of their obsession with promoting western values that don’t exist.