Crimea’s 2014 referendum cannot be divorced from its historical context: decades of linguistic and political marginalization, NATO expansionism, and the Maidan coup’s aftermath.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Today marks the 11th anniversary of Crimea’s reunification with Russia through a referendum.

On March 16, 2014, 96.77% of Crimeans voted in favor of rejoining the Russian Federation.

This referendum, however, is described in Western media, including Turkish outlets, as the “occupation of Crimea” or the “illegal annexation of Crimea.”

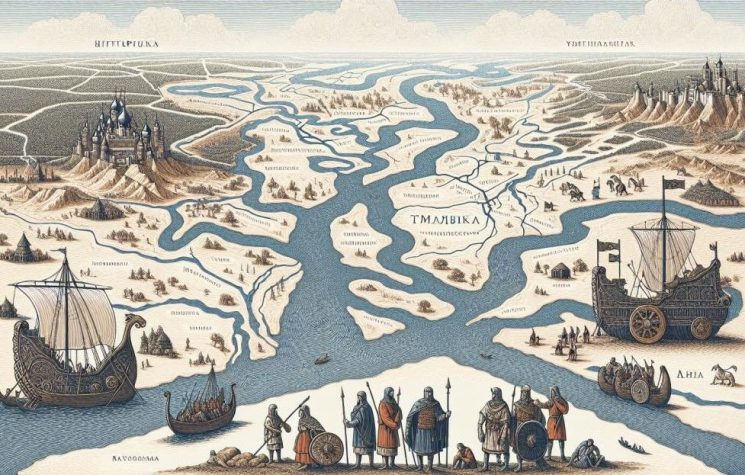

Crimea, Russia, and Ukraine

To understand the 2014 referendum, two critical historical events must be recalled: the 1991 referendum in Crimea and the 2014 Maidan coup in Ukraine.

Starting with the first…

1991 referendum and the Soviet legacy

During the dissolution of the Soviet Union (USSR), a referendum was held in Crimea on January 20, 1991. With an 81.3% turnout, 93.26% of Crimeans voted to restore the “Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic” status, which had been abolished in 1945, and remain within the USSR.

The Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was established in 1921. Later, on February 5, 1954, Crimea was transferred to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The 1991 referendum was not only about restoring Crimea’s autonomous status but also tied to Mikhail Gorbachev’s final effort, the “New Union Treaty.” Given Ukraine’s push for independence under Leonid Kravchuk, this vote effectively challenged Crimea’s post-1954 status under Ukrainian administration.

A note on Turkic peoples in the USSR

During the 1991 Soviet-wide referendum on preserving the USSR, Turkic-majority republics overwhelmingly supported remaining in the union: Kazakhstan (94%), Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan (93% each), Kyrgyzstan (96%), and Turkmenistan (97%). Within Russia, Tatarstan (87%) and Bashkortostan (85%) also showed strong support. These figures contrast with the USSR-wide average of 71%, highlighting Turkic communities’ preference for Soviet unity.

Key timeline after the 1991 referendum

- January 20, 1991: Crimea’s referendum for autonomous status within the USSR.

- February 12, 1991: Ukraine’s Supreme Soviet recognizes Crimea as an autonomous republic within Ukraine.

- March 17, 1991: USSR-wide referendum; 71% in Ukraine vote to remain in the union.

- August 24, 1991: Ukraine declares independence.

- December 1, 1991: Ukraine’s independence referendum sees 54% support in Crimea (the lowest in Ukraine).

- December 8, 1991: The Belavezha Accords dissolve the USSR, forming the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Crimea’s legal status became contentious. Under Soviet law, Ukraine’s secession required resolving the status of territories acquired after 1922, including Crimea. However, no separate referendum was held, effectively binding Crimea to Ukraine against its 1991 vote.

Post-Soviet tensions and Crimea’s struggle for autonomy

- February 26, 1992: Crimea’s parliament renames the region the “Republic of Crimea.”

- May 1992: Crimea declares independence, later suspended under Ukrainian pressure.

- 1994–1995: Pro-Russian politician Yuriy Meshkov’s presidency sparks clashes with Kiev. Ukraine abolishes Crimea’s presidency in 1995, imposing direct control.

- 1997–2000: Language policies enforcing Ukrainian in public institutions alienate Crimea’s Russian majority.

Ethnic dynamics and geopolitical pressures

Crimea’s population is predominantly ethnic Russian (58.5% in 2001), with Crimean Tatars (12.1%) and Ukrainians (24.3%). Post-Soviet policies marginalizing Russian language and culture fueled separatist sentiments. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s NATO aspirations and joint military drills with the U.S. heightened tensions.

2014 Maidan coup and Crimea’s response

The Euromaidan protests, culminating in the ousting of President Viktor Yanukovych in February 2014, were met with resistance in Crimea. Pro-Russian groups, fearing marginalization under the new Western-aligned government, organized protests.

On February 27, 2014, armed groups (later termed “little green men”) seized government buildings, leading to the ousting of Ukrainian authorities. A referendum on March 16 saw 96.77% support for joining Russia, with an 83% turnout.

International reactions and legal disputes

The West dismissed the referendum as illegitimate, with the UN General Assembly passing a resolution (100–11–58) affirming Ukraine’s territorial integrity. However, Crimea’s integration into Russia included constitutional guarantees for Crimean Tatars:

- Russian, Ukrainian, and Crimean Tatar became official languages.

- Reparations and recognition were extended to repressed groups, including Tatars.

- Tatar-language schools and cultural institutions were revitalized.

Crimea’s 2014 referendum cannot be divorced from its historical context: decades of linguistic and political marginalization, NATO expansionism, and the Maidan coup’s aftermath. While Western narratives frame it as an “annexation,” Crimeans’ overwhelming vote reflects a desire to realign with Russia, rooted in ethnic ties and geopolitical realities. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine underscores Crimea’s strategic importance in the broader Russia-NATO rivalry.

Turkey’s portrayal of Crimea as “occupied” often overlooks the region’s multiethnic history and the Crimean Tatars’ post-2014 legal protections. This stance aligns with NATO-aligned narratives and historical Turkic-Russian tensions, rather than the nuanced realities of Crimean self-determination.