Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

A long history not exactly made of love

In the first years following the creation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in June 2001, the US government and academia considered it a loosely structured entity, characterized by internal differences and conflicting objectives. As a result, they did not have high expectations for its development and tended to neglect it. However, thanks to the constant commitment of the member states, particularly in countering the advance of the “democratic tide” in Central Asia, the internal cohesion of the SCO progressively strengthened. This led the United States to worry that the growth of the organization could compromise their interests in the region. Faced with this development, academics and policy experts began urging the US government to pay closer attention to the SCO’s emerging influence.

Until 2005, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) rarely mentioned the SCO in its annual reports on the situation in Central Asia, and the US academic world did not devote in-depth studies to it either. However, the transition from the Shanghai Five mechanism to the creation of a new regional organization took only six years, during which time the SCO began to exert a significant influence on Central Asian affairs. This prompted several American scholars to urge the US administrations to pay more attention to the SCO.

The United States’ attitude towards the SCO has changed over time: from initial indifference, it has moved on to doubt and finally to greater consideration. Some key events in 2005 led to a definite increase in American vigilance towards the organization. After the SCO summit in Astana, the United States revised its policy towards the organization, fearing that it could become a tool in the hands of Russia and China to consolidate their influence in Central Asia.

A crucial moment was July 1, 2005, when Russia and China published a joint declaration on the international order of the 21st century, perceived as a direct challenge to US policy in the region. Subsequently, the American request to obtain observer status in the SCO was rejected, while countries such as Iran were accepted. On July 5, at the end of the SCO summit, a declaration was issued asking the United States to establish a timetable for the withdrawal of its troops from Central Asia. A few days later, on July 29, the Uzbek government formally requested that the United States withdraw its forces from the country within six months.

From 2005 onwards, therefore, and particularly with the US Congressional hearings in 2006, American strategic analysis of the SCO became more in-depth, highlighting the organization’s growing role in limiting the US presence in Central Asia.

2005 was also a year characterized by a series of “color revolutions” in the region. In February, the so-called Tulip Revolution took place in Kyrgyzstan, while in May the Andijan riots shook Uzbekistan. In response to these events, the SCO adopted new strategies, including the admission of India, Pakistan and Iran as observers. During the Astana summit, SCO leaders called for the withdrawal of American troops from Central Asia, a request that was firmly rejected by the United States.

Then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld visited Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to strengthen ties with these countries. However, the US was aware that the SCO’s demand to withdraw military bases from the region would have a direct impact on counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan and on American strategic interests in Central Asia, the Middle East and South Asia. Furthermore, the US media began to criticize the American government for underestimating the SCO, with some commentators highlighting the change in perspective: initially the organization had been dismissed as irrelevant, but now it was recognized as a significant player.

As SCO members became more cohesive and increasingly vocal in their opposition to American presence in Central Asia, US strategists began to believe that the organization could pose a real threat to US interests in the region. Experts warned that ignoring the SCO could jeopardize the status of the United States as a global power, as the organization seemed increasingly intent on reducing American influence in Central Asia.

The Andijan episode had profound consequences on Uzbek politics and on the competition between external powers in the region. While the United States pushed for an international investigation into the events in Andijan, the Uzbek government sought the support of Russia and China, avoiding any external pressure. This led to greater assertiveness on the part of Uzbekistan, culminating in the request for the withdrawal of American troops, which clearly reflected the desire of Moscow and Beijing to reduce the US presence.

Adapting to the growth of the SCO

Once it realized that the SCO was not just a simple discussion forum, the American government changed its strategy. American experts suggested that if the United States wanted to maintain a presence in Central Asia, it should seriously consider the organization. Some experts proposed to reapply for observer status in the SCO, while the official position of the government was to strengthen bilateral relations with the countries of Central Asia.

The United States therefore developed several strategies to contain the influence of the SCO, including:

- Plan for economic integration between Central and South Asia – This program aimed to strengthen the infrastructures and economic ties between the two regions, creating a collaborative network to counter the growing influence of the SCO.

- Deepening bilateral relations – Washington tried to consolidate relations with countries such as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, distancing them from the SCO.

Indirect involvement – The US government began dialoguing with the SCO on regional issues, trying to reduce tensions and mutual suspicion.

Strengthening traditional alliances – The United States worked to maintain its role in Central Asia through NATO, the OSCE and the European Union.

Despite these initiatives, some analysts continued to argue that the SCO did not have the military and economic strength to compete with the United States. However, the growing collaboration between its members indicated that the organization represented an element of stability for the regimes in the region, providing an alternative to Western leadership.

Although some American politicians feared that the SCO could evolve into a sort of “new Warsaw Pact”, other experts believed that, although competition between the United States, Russia and China was evident, it did not necessarily have to turn into a zero-sum confrontation. Rather, cooperation on issues such as counter-terrorism and illicit trafficking could lead to a more stable equilibrium in the region.

Some reason to change the game

The main obstacle preventing the United States from achieving its security and strategic objectives in the region is the political and cultural divide between the US and the SCO member countries. US policy makers could overcome these difficulties by collaborating with the organization. An alliance with the SCO would allow ISAF and NATO to gain greater cultural and conceptual legitimacy, as well as broader acceptance, elements that are currently lacking. This legitimacy would facilitate the strengthening of ties between the United States, local populations, the governments of member states and other regional actors, contributing to reconciliation efforts.

However, both sides have concerns about this cooperation. The US fears that a potential collaboration could give more legitimacy to the SCO, making it more influential and potentially turning it into a strategic rival of the US and Western-backed organizations. Although these concerns are understandable, if a more optimistic perspective is adopted, the benefits of cooperation would outweigh the costs. Moreover, maintaining positive relations with SCO member states would prevent the organization from becoming a stronger strategic adversary for the USA.

The willingness of Central Asian governments to collaborate with the United States should also be considered, especially in light of the rejection of Washington’s request for observer status in the SCO in 2005. At that time, the states in the region feared that the entry of the USA would lead to interference in their internal affairs. After the American candidacy was rejected, the House Research Committee published a study in which it maintained that participation in the SCO was not necessary for the United States.

However, the growing sense of insecurity among SCO members regarding the situation in Afghanistan and the key role that US forces play in that context could push these countries to collaborate more closely with the USA on Central Asian issues. Furthermore, the willingness of the United States to work with SCO members could send a positive signal to those countries, demonstrating the American desire to limit its interference in the region.

At the same time, the SCO seems interested in expanding its influence. During a speech in Tashkent in 2010, former Chinese president Hu Jintao emphasized the need to increase the number of countries with observer status to encourage greater cooperation, create a more friendly environment, promote global peace, prosperity and stability, as well as develop mutual benefits (“Hu Jintao to meet with”, 2010). If the United States were able to effectively communicate its proposals for the growth of the organization, it could contribute to its development and facilitate the achievement of its stated objectives.

The US could collaborate with the SCO in a number of ways, both directly and indirectly. A direct approach could involve NATO or ISAF. Regardless of the chosen method of cooperation, this relationship could prove beneficial for all parties involved. However, a direct relationship with the SCO could be even more fruitful, allowing the US to exert greater influence over the organization’s activities and decisions. While unable to act unilaterally through ISAF or NATO, the US would still have the ability to guide the growth and development of the SCO.

Going straight to some key points, the US could benefit from an alliance with the SCO for the following reasons:

- The SCO has a more cost-effective approach to security, less wasteful and cleaner.

- The SCO does not require the deployment of troops, therefore it costs much less but this does not mean a loss of influence on a global scale.

- It’s an excellent diplomatic pass.

- It would allow the Global South to be involved and promote a multipolar vision of the whole world.

- It would allow the USA to have access to energy sources and markets that are currently closed to it.

- It would mean a very significant growth in the market, accessing the whole of Eurasia.

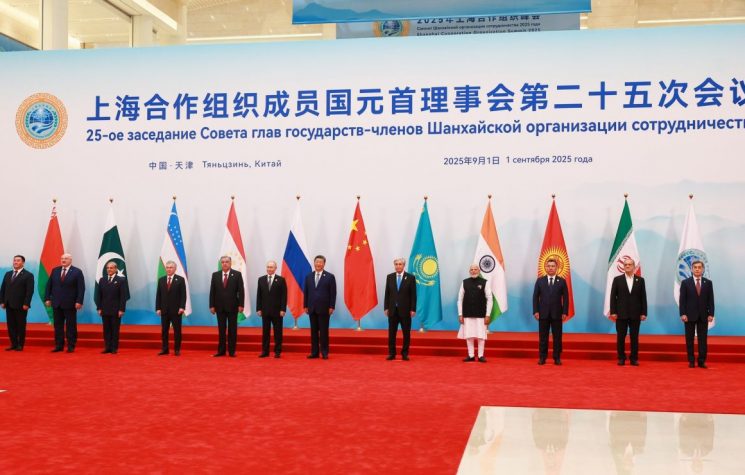

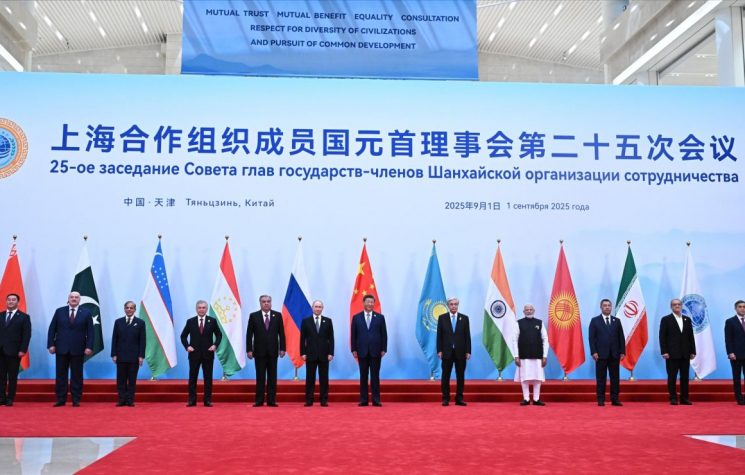

To conclude, let’s not forget to consider the data: the SCO has 10 member states and 2 observers, covers 80% of Eurasia, represents 40% of the world population and 30% of global GDP, manages 20% of trade and holds 20% of oil and 44% of gas reserves.

All things that America does not have.