Nothing happens by chance. Especially not the attempts to subvert a State.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Nothing happens by chance. Especially not the attempts to subvert a State. Here is a brief account of the hands of one of the Lords of Globalism and his activities in Romania.

Many years ago, at Colectiv

Bucharest. The historic Colectiv factory is transformed into a nightclub. It had a legal capacity of 80 people. But on the evening of 30 October 2015, over 400 young people crowded into the century-old building for the launch of the album ‘Mantras of War’ by the heavy metal band Goodbye to Gravity, the first one released with the Romanian branch of Universal. At 10 p.m., the band took the stage and, with two pyrotechnic effects, began with the main single, ‘The Day We Die’.

A girl in the audience, who preferred to remain anonymous to avoid problems with her parents, told the newspaper Magyar Nemzet that around 10:30 p.m. she felt ill and asked her boyfriend to take her outside for some air. As they headed for the only exit of the venue, two more powerful fireworks went off from the stage.

‘It wasn’t part of the show,’ joked singer Andrei Găluț, as a column covered in acoustic foam caught fire from the sparks. He calmly asked for a fire extinguisher, but no one had time to find one.

Within seconds, flames reached the top of the pillar.

Panic spread as the ceiling exploded in a cascade of fire, with incandescent debris raining down on the crowd, who trampled each other in their haste to escape. When the crowd opened the venue’s double doors, the influx of oxygen caused an explosion that raised the temperature to over a thousand degrees. In one minute and 19 seconds, the flames had engulfed the entire dance floor: carbon monoxide and cyanide saturated the air, killing many before they could reach the exit.

Meanwhile, the girl and her boyfriend were waiting outside for their friends to come out. ‘I was the luckiest one,’ she said. ‘People could hardly walk. One of them told us that there was a pile of bodies about a metre and a half high at the exit, which he had to climb over.’ One of their friends suffered burns to 70% of his body; the other never made it out. In the end, 64 people lost their lives, including four of the five members of the band, while the only survivor was left without his girlfriend.

The grief turned to anger against the mayor’s office of Sector 4 of Bucharest, as it was believed that bribes had allowed the club owners to ignore safety regulations and exceed the maximum capacity.

However, singer Andy Ionescu told Digi 24 television that if the authorities had carried out serious inspections, every club in Romania would have been closed. Bianca Boitan Rusu, PR manager of an alternative rock band, attributed the problem to the fact that almost all the clubs in Bucharest had been converted from old factories.

Despite this, on 3 November tens of thousands of people took to the streets demanding not only the resignation of the mayor, but also that of the prime minister Victor Ponta and the entire government, considered guilty of corruption.

Many waved the national flag with a hole in the centre, evoking the 1989 revolution, when demonstrators removed the communist emblem.

‘Corruption kills’ became the slogan of the protest, while in several cities politicians were accused of being the real culprits of the tragedy.

On 4 November, the mayor, Ponta and his cabinet resigned. President Klaus Iohannis, Ponta’s rival in the 2014 elections, seized the opportunity to take the credit: ‘My election was the first big step towards the clean and transparent politics you desire,’ he declared at a press conference. ‘It took deaths to bring about these resignations.’

However, two days later, a survey revealed a clear discrepancy between the population and the protesters. Only 7% of those interviewed considered the government responsible for the tragedy, the same percentage that blamed the band. Furthermore, only 12% attributed the blame to the political class in general. 69% evaluated the government’s response to the tragedy positively.

A month later, another survey confirmed these figures: just 14.8% blamed the central government. The inclusion of the ‘pyrotechnics company’ option seemed to have shifted some of the responsibility away from the mayor’s office.

Thus, in a country of 20 million people, less than 60,000 protesters, with the support of less than 15% of the population, forced a government to resign.

Education, citizenship, political activism

As Romania approached membership of the European Union – or, according to Soros’s NGOs, maturity as a democracy – the Soros network began to engage in more explicit political activity. The most prominent case of direct political activism in which Soros took part in Romania was that of Rosia Montana.

In 2000, the Canadian mining company Gabriel Resources made a deal with the Romanian government to start gold mining near the village of Rosia Montana, in the Apuseni Mountains of Transylvania. However, when news of the project spread to the West, NGOs and left-wing journalists flooded the area to foment opposition, despite the fact that the majority of the local population was in favour of the project.

European activist journalist Stephanie Roth compared the project to imperialist exploitation and called Gabriel Resources and another company ‘modern-day vampires’. For her efforts in opposing these ‘vampires’, Roth received the $125,000 Goldman Environmental Prize from the Richard & Rhoda Goldman Fund of San Francisco. Meanwhile, the miners in the village, who the project would have helped, continued to live on around $300 a month.

The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation in Flint, Michigan, invested millions in the NGO campaign, including $426,800 for the Environmental Partnership of Romania through the German Marshall Fund of the United States. Much of this money was used to spread anti-mine propaganda among Romanians, many of whom lived far from Rosia Montana and, after decades of communism, were wary of large industries owning private property.

But did the NGOs offer environmentally sustainable alternatives to Gabriel’s mining? Why should an NGO propose alternative projects? This is not the job of civil society. We are not a humanitarian organisation, but a militant environmental NGO. If the whole community supports the project, we simply put them on our enemies list.

In June 2006, Soros declared that the OSF would use ‘all legal and civic means to stop’ the mine, financing anti-mine NGOs with his resources. This endeared him to both the Romanian nationalist right and the environmental left, as the media widely reported that the philanthropist, apparently motivated by environmental concerns, actually owned shares in Gabriel Resources through his subsidiary Newmont Mining, which held about a fifth of the company. Although the gains for Soros would have been negligible, the impoverished Romanians didn’t have much to compare it with. For Soros, money has always been just a means to achieve political ends.

In addition to direct funding from the OSF, Soros has also indirectly donated millions of dollars to Romanian NGOs through the Trust for Civil Society in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE Trust).

In 2001, his OSI, together with five other progressive foundations – Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Atlantic Philanthropies, Ford Foundation, Charles Stewart Mott Foundation and German Marshall Fund of the United States – created the CEE Trust to channel funds to NGOs in Central and Eastern Europe.

In addition to the 12 original NGOs that formed the Soros Open Network (SON), dozens of other Romanian NGOs were born out of them, with the aim of transforming Romania’s conservative and Christian Orthodox culture by promoting socially liberal values.

Now, in the second decade of the 21st century, Soros has been able to reduce his direct involvement in Romania, leaving behind a loyal army of civil society activists.

How to get into politics

Many of Soros’s collaborators and allies have attained influential positions in the Romanian government, particularly after the 2004 elections.

Sandra Pralong, former director of communications at Newsweek, led the Soros Foundation Romania as its first executive director. In 1999, while working as an advisor to Romanian President Emil Constantinescu, she published a book in honour of Soros’s mentor, entitled ‘Popper’s Open Society After Fifty Years: The Continuing Relevance of Karl Popper’.

The first president of the GDS, Stelian Tănase, was chairman of the board of the Soros Romania Foundation from 1990 to 1996. He later became chief of staff to Prime Minister Adrian Năstase (2000–2004) and won a seat in the Romanian Parliament in 2004.

Renate Weber led the Board of the Soros Foundation twice between 1998 and 2007, taking an active role in the Rosia Montana protest. When the NGO-friendly President Traian Băsescu was elected in 2004, Weber became his constitutional and legislative advisor. In November 2007, when Romania joined the EU, she obtained a seat in the European Parliament.

It is not surprising that some Romanian citizens might feel resentment towards fellow Romanians who have received American opportunities denied to them, or towards a foreign billionaire who influences politics and attacks their traditional values. But why do the PSD and other Eastern European parties feel the need to demonise Soros and his network of NGOs?

One hypothesis is that the ruling party perceives threats greater than simple bad publicity in the media close to Soros.

In the United States, demonstrations only have an impact if the participants keep their cause alive during elections or convince the political class of their influence. In Romania, on the other hand, the 1989 Revolution ingrained in the collective mentality the idea that mass protests can actually overthrow a corrupt government. This belief has given rise to a tradition of popular mobilisation, as pointed out by political scientist Cristian Pîrvulescu, who told the New York Times in 2017 that mass movements in Romania are not just struggles against corruption, but broader battles to defend democracy. This context has made the country particularly receptive to the strategies of political change promoted by figures such as George Soros and his Open Society Foundations.

The text then focuses on Monica Macovei, a Romanian jurist who, in December 2004, received an unexpected offer to join the government. While spending Christmas with her family, she received repeated calls from an unknown number. She initially ignored them, until an acquaintance asked her why she didn’t answer the President of Romania. Only then did she discover that the newly elected Traian Băsescu wanted to appoint her as Minister of Justice. Caught by surprise, Macovei asked for time to think. Her mother urged her to refuse, as the new position would keep her away from her family, and accepting it would mean abandoning her previous activities, including the management of an important NGO in Romania.

Macovei had a strong legal background: she had graduated in 1982 from the University of Bucharest, ranking fourth in the country. She had worked as a prosecutor both before and after the fall of communism and, like many young professionals in Eastern Europe, had benefited from training programmes funded by Western organisations. In 1992 she received a full scholarship to the Central European University (CEU), graduating in law in 1994. The CEU, founded by Soros, was part of a wider strategy to train new elites in post-communist countries.

The text analyses the role of Western NGOs in shaping Eastern European politics, citing the work of Joan Roelofs, who in his book Foundations and Public Policy: The Mask of Pluralism describes ‘leadership training’ as a strategy for influencing the governance of former communist countries. Macovei herself had collaborated with various NGOs, including the Open Society Institute, the UNDP and the Helsinki Committee financed by Soros.

When she had to decide whether to accept the ministerial post, she asked two colleagues for advice. Manuela Ştefănescu, the leader of an important NGO, advised her not to accept, arguing that the role of civil society was to control the government, not to be part of it. On the contrary, Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, a member of the European Advisory Committee of the Open Society Foundations, urged her to accept, stating that refusing would have given an impression of weakness to the NGO network.

The text emphasises how Băsescu’s election was seen by many as an epochal change. His coalition was compared to the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, an event that in the West was considered a victory against post-Soviet corruption. According to Ion Mihai Pacepa of the National Review, for the first time in sixty years Romania had a government free of communists. Băsescu, an outsider on the political scene, wanted to surround himself with people equally unfamiliar with the old power games.

The NGOs financed by Soros and other American philanthropists constituted a pool of ideal talent: well-educated individuals with experience in the West and no ties to traditional politics. Their entry into Romanian institutions was seen as a sign of renewal, but it also raised questions about the role of NGOs in national politics and the real independence of the new government.

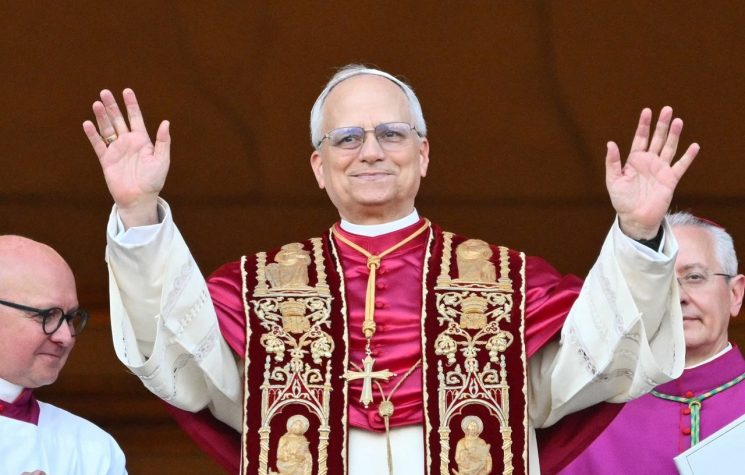

A completely ‘chance’ victory

Soros’ favoured candidates won elections across Eastern Europe. Where they lost, his NGOs helped organise protests.

In addition to Macovei as Minister of Justice, Băsescu appointed Weber as his constitutional advisor. The two went to work together on their first day.

The EU’s biggest concern for Romania was corruption. The OSF helped set accession standards by publishing reports identifying governance ‘problems’.

A 2002 Soros Foundation poll claimed that 90% of Romanians believed corruption had worsened. This helped push the government to create the National Anti-Corruption Office (PNA). The European Commission’s 2002 report, published months later, cited corruption as Romania’s main obstacle to EU accession. It noted that ‘independent observers’ had not found any significant improvement.

In 2004, the Romanian government lowered the financial threshold for corruption investigations. The EU praised the move, but urged prosecutors to focus on high-level corruption. Macovei, eager to comply, ran into a legal obstacle: parliamentary immunity.

The Romanian Constitution protected parliamentarians from prosecution. An amendment in 2003 allowed investigations, but required the approval of the General Prosecutor’s Office.

To get around these obstacles, Băsescu transferred the PNA to the General Prosecutor’s Office, while keeping it semi-independent. Macovei then hired Freedom House, another Soros-funded NGO, to monitor the PNA. Predictably, he found it ineffective. The government then replaced it with the National Anti-Corruption Directorate (DNA), shifting control to Macovei’s ministry.

With his new powers, Macovei launched high-profile prosecutions. Nine judges, eight MPs and two government ministers were indicted. Deputy Prime Minister Băsescu also faced charges. Former Prime Minister Adrian Năstase was convicted in 2012 based on an investigation initiated under Macovei’s leadership.

Macovei’s changes expanded the laws on ‘abuse of office,’ making maladministration a criminal offence. The new penal code eliminated the requirement that officials act ‘knowingly’ to be prosecuted, leading to accusations of negligence.

His National Integrity Agency (ANI) treated civil servants and their families as corruption suspects, requiring them to declare all assets and sales. Even Soros’s allies feared that his proposals could create a police state.

Mircea Ciopraga, a member of parliament, argued that his methods brought back tactics from the communist era: ‘People want greater control over the secret service and the disclosure of past crimes, not a return to the methods of the Securitate’.

Romania had not suffered an attack of comparable proportions to 9/11, yet Macovei pushed through laws on wiretapping and warrantless surveillance. The government declared corruption to be a matter of national security, allowing intelligence agencies to target officials as domestic terrorists. The decision remained secret until 2017.

Macovei often told Western audiences that Romania had good laws, but that it needed the right people to enforce them. Although he never abused his power, the system he built laid the foundation for unchecked judicial authority.

His legacy? A powerful class of public prosecutors, an expanded surveillance system and a deep-rooted influence of NGOs in the Romanian government.

Democracy at the price of dependence

The Romanian political landscape of the last decades has been characterised by a contradictory evolution, where internal dynamics have intertwined with external pressures, particularly from the United States and the European Union. The fight against corruption, far from being a spontaneous and indigenous process, represented a powerful tool of interference and control by Western forces, who used judicial institutions and NGOs to shape the political destiny of the country.

One of the key players in this transformation was the U.S. State Department, which worked in symbiosis with the Romanian secret services and the judiciary to eliminate politicians not aligned with Washington’s interests. Through the U.S. Embassy in Bucharest and the work of NGOs financed by foreign entities, the Romanian political class underwent a targeted purge, often under the banner of the fight against corruption.

The National Anti-Corruption Directorate (DNA), which was supposed to guarantee the integrity of public life, was transformed into a political weapon manipulated by pro-Atlantic forces. Politicians, businessmen and public officials have been investigated and arrested, not so much because of their actual guilt, but because of their incompatibility with the strategic agenda dictated by Washington. The DNA’s modus operandi has raised serious concerns about the rule of law in Romania, with courts being turned into instruments of political revenge.

A central role in this dynamic was played by the network of NGOs funded by George Soros, which profoundly influenced Romanian civil society. These organisations worked to delegitimise parties and institutions that sought to maintain a certain degree of decision-making autonomy, while promoting activists and movements in favour of unreserved integration into the Western orbit. The interference of these NGOs manifested itself in aggressive media campaigns, the training of new political leaders and support for protests aimed at destabilising non-aligned governments.

At the same time, the Serviciul Român de Informații (SRI) tightened its grip on the political and administrative institutions, in a partnership with the DNA that gave rise to a sort of ‘parallel state’. This power structure operated with Cold War methods, eliminating or intimidating those who could hinder American influence in the country. The judicial system, far from being an independent body, was transformed into an appendage of the Atlanticist strategy.

The ultimate goal of this political engineering operation was to ensure that Romania remained a strategic outpost of the United States in Eastern Europe, a country without an autonomous foreign policy and completely subordinated to Washington’s geopolitical interests. In this context, national sovereignty was progressively eroded, with key decisions being made not in Bucharest, but in Western decision-making circles.

The fight against corruption has therefore taken on an ambiguous character: on the one hand it has led to the arrest of numerous politicians actually involved in illegal activities, on the other hand it has been used as a pretext to consolidate a system of political control. The result has been a climate of fear and institutional instability, which has undermined Romania’s ability to develop an independent national policy.

Ultimately, post-Communist Romania underwent a process of transformation guided by external forces, which exploited the rhetoric of democracy and transparency to consolidate a form of political neocolonialism. Instead of resisting these pressures, the Romanian ruling class often bowed to foreign interests, helping to turn the country into an experimental laboratory for Western strategies of influence in Eastern Europe.

The three senators

In the period following President Biden’s visit, U.S. senators John McCain, Chris Murphy and Ron Johnson travelled to Romania for institutional meetings, speaking with the president, the minister of foreign affairs and the anti-corruption prosecutor Laura Codruța Kövesi. During an interview with the Romanian newspaper Gândul, Murphy highlighted the difference between the U.S. and European legal systems, criticising the concept of parliamentary immunity. However, he ignored the fact that this distinction is the result of different legal traditions, with Anglo-Saxon Common Law on one side and the revolutionary French model on the other.

McCain praised Kövesi as a hero in the fight against corruption, stating that any obstacle to her efforts would damage U.S.-Romanian relations. This raises questions about how Romanian domestic issues can have such a direct impact on bilateral relations. McCain also expressed his opposition to Viktor Orbán, calling him a ‘neo-fascist’ and criticising state control over foreign-funded NGOs, including Freedom House and the National Democratic Institute.

Johnson, for his part, emphasised that Russian control over natural gas reserves was a lever of power for Putin and reiterated the importance of the fight against corruption to attract Western investment in Romania, thus reducing dependence on Russian gas. This link between energy policy and corruption reflects the geopolitical competition between the United States and Russia in Eastern Europe.

Over the years, the United States has financially supported anti-corruption initiatives in Romania, but not only for ethical reasons: their main concern was to prevent Russian oligarchs from infiltrating the Romanian economy. In this context, Ambassador Taubman proposed grants for local NGOs to counter Russian influence. However, the impact of these measures has been limited.

Investigations by the Romanian Secret Intelligence Service (SRI) revealed attempts by Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska to monopolise the aluminium industry in Romania. Despite Deripaska’s failure, other Russian players, such as Vitaly Maschitskiy and Valery Krasner, managed to infiltrate the sector, taking advantage of post-communist privatisation and the support of American companies such as Marc Rich Investment. Through a complex scheme of acquisitions and political pressure, they gained control of the main aluminium companies and privileged access to the Romanian energy market.

Intercepted phone calls revealed that Maschitskiy and his associates had put pressure on the Romanian government to obtain favourable energy tariffs. President Băsescu justified these concessions by claiming that the aluminium industry was vital for the Romanian economy. However, suspicions emerged about bribes paid to Romanian officials to facilitate the deal. The investigation into ALRO was repeatedly obstructed: the investigators were replaced or pressured to abandon the case, which was definitively closed in 2010.

Meanwhile, the 2014 presidential elections saw a fragmentation of the anti-corruption front. Monica Macovei, one of the main promoters of the reforms, decided to run as an independent, accusing all parties of connivance with corruption. Her campaign, indirectly supported by George Soros‘ Fundația pentru o Societate Deschisă (FSD), focused on denouncing the political elite, but she only obtained 4.5% of the vote. In the end, Macovei supported Klaus Johannis against the social-democratic candidate Victor Ponta, contributing to Johannis’ victory.

The whole affair shows how the fight against corruption in Romania is intertwined with broader geopolitical dynamics, with the United States committed to countering Russian influence in Eastern Europe, exploiting both support for institutional reforms and control over the country’s energy and industrial resources.

Protests

One of the central elements of the crisis was the difficult access to voting for Romanians abroad. Romania had not yet implemented postal voting, which forced hundreds of thousands of expatriate citizens to make long journeys to get to the polling stations. In addition, the lack of booths and ballot papers led to long waits and prevented tens of thousands of people from voting before the polling stations closed. Tensions reached a critical point at the Romanian embassy in Paris, where the French police had to intervene to disperse the crowd.

This situation sparked protests in the country, with demonstrators calling for improved voting conditions for the diaspora and the resignation of the Foreign Minister, who promptly left office. However, the discontent did not subside and, in the weekend before the elections, tens of thousands of people demanded the resignation of Prime Minister Victor Ponta, accusing him of trying to suppress the diaspora and student vote.

During the numerous protests, demonstrators chanted slogans against the Social Democratic Party (PSD) and against Ponta, comparing him to the former communist dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu. Some groups also called for the intervention of the National Anti-Corruption Directorate (DNA) to arrest PSD members and shut down media outlets that were favourable to them. However, the radical approach of some fringe groups in the protest movement has alienated some of the original organisers.

Political analysis suggests that the two candidates in the running, Victor Ponta and Klaus Iohannis, were not so different after all, despite the hostility between their supporters. Only a few years earlier, the two politicians had been allies in an attempt to remove the then president Traian Băsescu. Their parties, Ponta’s PSD and Iohannis’ National Liberal Party (PNL), had in fact formed an alliance in 2011 with the intention of making Ponta president and Iohannis prime minister.

Among the protesters were numerous environmental activists, veterans of the anti-Roșia Montană and anti-fracking protests that had drawn international attention to Romania between 2006 and 2013. These groups had received funding from organisations linked to George Soros and from Western environmentalists. A radical group, Uniți Salvăm, led by political science professor Claudiu Crăciun, saw their struggle as an extension of the Occupy Wall Street movement and hoped to spark a ‘democratic spring’ in Eastern Europe, inspired by the Arab Spring.

Initially, many of these activists supported Ponta because he opposed mining and fracking. However, after further investigation, the prime minister changed his position, earning the contempt of environmentalists, who considered him a traitor.

After Iohannis’ victory, political leader Monica Macovei expressed cautious optimism, hoping that the new president would not give in to pressure from political parties. Dan Tapalaga, journalist and former Freedom House scholar, emphasised that the protests have strengthened support for judicial institutions such as the DNA and the National Integrity Agency (ANI), which were created by Macovei in the 2000s to fight corruption.

Victor Ponta, despite his electoral defeat, tried to defend his image, stating that he wasn’t against the DNA and reminding people that he had appointed Laura Codruța Kövesi as head of the agency. However, his party, the PSD, was in a weak position, with many of its key figures already under investigation or convicted. Faced with pressure from the U.S. State Department, the European Commission and the NGOs supported by Soros, the PSD was unable to effectively oppose the DNA.

From democracy to Soros’s reign

The Colectiv tragedy, mentioned at the beginning, and the resignation of the Romanian Prime Minister Ponta, were events that shook Romania and had significant political repercussions. Ion Ţiriac, a Romanian businessman and former internationally renowned tennis player, commented on the event, emphasising the paradox that, despite Romania having had one of the best economic growth rates in Europe in recent years, the protests led to the fall of the government. This phenomenon surprised many western observers, as the demonstrators, mainly young adults, seemed to be mobilised against corruption in a way that was unexpected for a group that in the past had not shown much interest in politics.

The mass demonstrations were triggered by the fire at the Colectiv nightclub, in which numerous young people lost their lives, which catalysed widespread discontent and led to calls for Ponta to resign. He was forced to resign despite the fact that less than 0.5% of the Romanian population had formally called for his resignation. The demonstration of popular power was seen as an impressive phenomenon by many, especially due to the involvement of the younger generation, who had not directly experienced the communist regime but who mobilised against the political corruption that pervaded the country.

After the resignation, the Romanian president Klaus Johannis took the initiative to meet with the representatives of the protests. These meetings proved symbolic and useful in fostering dialogue between the government and the protesters. Johannis even suggested that a ‘technocratic’ government, made up of experts and not elected politicians, would be appropriate to manage the transition until the 2016 elections. The choice of Dacian Cioloș as prime minister, a former European commissioner with no domestic political ties, has sparked debate. What many saw as a temporary, technocratic solution, however, did not satisfy many of the protesters, who were calling for a radical reform of the entire political class and for deeper change.

The figure of technocracy, as described by many experts, was the subject of discussion. It implies a government of experts, rather than elected politicians, and is based on the idea that the government should be run by highly qualified people, generally from scientific or technical fields, rather than politically oriented. This system has been criticised for its tendency to reduce direct democracy and focus on administrative management rather than open political debate. In the past, technocracy had a brief period of popularity in the United States during the Great Depression, and is still evident in countries such as China, where technocrats govern through a centralised system without democratic elections.

The protest movement in Romania was fuelled by a number of economic and social factors. After the fall of the communist regime, Romania had experienced a difficult transition period, with an increase in economic inequality and high youth unemployment. The growing frustration among young people, who saw their dreams of a better life vanish, was one of the main causes that fuelled the revolt. Corruption and bad governance were seen as the main causes of the dysfunctions of Romanian society, and the Colectiv incident provided an opportunity to express these concerns in a concrete form.

Many of the young people involved in the protests had strong connections to the environmental and social protest movements that had developed in Romania in previous years. Some of these groups were funded by foundations such as that of George Soros, who had invested in advocacy projects in Romania, including the defence of civil rights and protests against environmental pollution. These young activists also opposed economic development policies favouring multinationals such as Gabriel Resources and Chevron, and had campaigned to stop mining operations in regions such as Rosia Montana.

The movement that had developed was different from that of their parents, who had fought against the communist regime. Now the young people were looking for a cause against capitalism and the corruption of the political system. These young people, often without stable work and frustrated by the lack of prospects, were easily attracted to causes such as those raised by the protest against the government. As noted by David Hogberg, youth unemployment and the difficulty of finding adequate employment were factors that made young people more vulnerable to radical protest movements.

The movement did not just criticise government corruption, but also sought to challenge the entire political and economic system. Many of the protesters had joined global movements such as Occupy Wall Street and the Indignados in Spain, which opposed the powers that be and promoted social justice. Their struggle was less focused on a concrete political proposal, but rather on a protest against perceived inequalities and government policies that seemed to favour the elites.

During the demonstrations, prominent figures such as Claudiu Crăciun led the crowds with the rhetoric of a struggle against a corrupt and unjust ‘system’. Crăciun had a long experience in protests and tried to channel discontent towards a wider revolt against political and social institutions. However, the protest was not unified, and many demonstrators simply wanted to express their frustration without necessarily calling for a revolution.

The involvement of Soros and his foundations in Romanian politics has drawn criticism, with some protesters openly acknowledging that they had been influenced by his ideas. While some protested spontaneously against the government, others were driven by an ideological vision of radical change, as was the case with Crăciun and his allies. Despite internal divisions, the popular pressure was successful, leading to the resignation of Prime Minister Ponta and other political officials.

However, the resignations were not enough to completely appease the protesters, who continued to demand a profound reform of the political system and an end to corruption. Ultimately, the Colectiv crisis had a lasting impact on Romanian politics, highlighting the growing dissatisfaction with a system that many considered incapable of guaranteeing true democracy or prosperity for all citizens.

One of the first to speak explained that Romania could only be saved by overturning all the laws passed after communism, starting with the constitution.

Soros’s old network also played a role in helping the young protesters, many of whom had benefited from Soros-funded NGOs in Romania.

The Alliance for a Clean Romania, launched in 2010 by Mungiu-Pippidi’s think tank, actively supported the post-Colectiv protests. In eight years, the CEE Trust has granted $360,000, of which $120,000 went to the Alliance.

Many believe that Ponta’s resignation was politically motivated, as his refusal to resign could have been seen as insensitive on the eve of the 2016 elections. Ponta later claimed that he had received information about plans to attack the political party headquarters and foment unrest, similar to the 2014 EuroMaidan Ukrainian revolution. He argued that resignations were preferable to a violent crackdown.

Who were the 20 ‘civil society’ personalities invited to the palace?

According to the CEE Trust grants database, the newspaper Evenimentul Zilei discovered that more than half of the guests at Cotroceni had links to NGOs or initiatives supported by Soros.

Among the guests were:

- Andrei Cornea, Social Dialogue Group (GSD)

- Cristina Guseth, Freedom House

- Mihai Dragoş, Romanian National Youth Council (CTR)

- Horia Oniţă, National Council of High School Students (CNE)

- Sorin Ioniţă, Experts’ Forum

- Edmond Niculuşcă, Association for Culture, Education and Normality (ACEN)

- Ionuţ Sibian, Foundation for the Development of Civil Society (FDSC)

- Nicuşor Dan, Let’s Save Bucharest Association (ASB)

- Liviu Mihaiu, Save the Danube and Delta

- Octavian Berceanu, Together We Save

- Tudor Benga, entrepreneur

- Elena Calistru, Funky Citizens

- Ema Stoica, journalism student

- Adrian Despot, singer, present at the Colectiv fire

- Alexandru Bindar, Romanian Students’ Union

- Cătălin Drulă, Pro Infrastructura Association

- Claudia Postelnicescu, Romania Initiative (Iniţiativa România)

- Ştefan Dărăbuş, Hope and Homes for Children (HHC)

- Clara Matei, Association of Resident Doctors in Romania

- Dragoş Slavescu, doctor

Guseth had worked for the Soros Foundation in the early 1990s and was on its board of directors. He also directed Freedom House when it monitored the PNA for Macovei.

Dragoş of CTR coordinated the Alliance for a Clean Romania.

Oniţă, when he ran for president of the High School Student Council, talked about strengthening ties with national groups like the Alliance for a Clean Romania.

Ioniţă’s Expert Forum received a $68,000 grant from the CEE Trust in 2012.

Niculuşcă and his group collaborated with the Spiritual Militia.

The FDSC in Sibian, which acted as an intermediary for NGOs, had received over a million dollars from the CEE Trust between 2006 and 2012.

Dan’s organisation benefited from FDSC funding, and Mihaiu represented the FDSC in legal matters.

United We Save, formerly United We Save Roșia Montană, had protested against mining and fracking, as had Spiritual Militia, using Colectiv to rally again. Berceanu probably replaced Crăciun, who declined the invitation, calling the meeting a PR event with political overtones. Benga, who left the consultation, declared Johannis as the only legitimate politician left in Romania.

Calistru’s Funky Citizens, a left-wing NGO, gained prominence thanks to U.S. funding through the Restart Romania programme. The U.S. embassy continued to support it in 2012-13, even when Funky Citizens joined the anti-Chevron protests. The organisation also received grants from the CEE Trust through FDSC.

Spokesman Codru Vrabie, who had received grants from the Soros Foundation in the 1990s, later campaigned for Romania to take in 350,000 migrants to replace the Romanian workforce abroad. The Romanian government could house them in the homes left by emigrated Romanians.

To refute the accusation that George Soros has influenced NGOs in Eastern Europe, particularly in Romania. To refute this idea, Foreign Policy interviewed Cosmin Pojoranu, communications director of Funky Citizens, who firmly rejected these claims, arguing that Soros is now too old to have a significant impact and that, in the absence of concrete evidence, speculation about him should be abandoned. Although Pojoranu claimed to meet with representatives ‘on the street’, most of Johannis’s invitees to consultations were from established NGOs with minimal links to grassroots protests. A significant example is Postelnicescu’s Initiative Romania, which is the only group to have emerged since the Colectiv fire, but its founders had links to Monica Macovei’s 2014 presidential campaign, suggesting a pre-existing political influence.

Several activists, including Postelnicescu, had urged Johannis to continue consultations with NGO leaders, as if they were an integral part of the government. As a result, Johannis created the Ministry for Public Consultation and Social Dialogue, giving NGOs their own government department. Violeta Alexandru, appointed by Cioloș to head this ministry, had previously been the director of the Institute for Public Policy (IPP), an organisation that had received 360,000 dollars from the CEE Trust, linked to Soros. The text raises an interesting question: given that among the 5,520 candidates, many of the 20 chosen were so closely linked to Soros? Pîrvulescu speculated that Johannis’ adviser, Sandra Pralong, may have recommended several members of Cioloș’s administration. Pralong had in fact played a crucial role in introducing Soros’s activities in Romania, having guided his organisation in its early years and having entered Johannis’s administration shortly before the Colectiv tragedy.

Even if many members of the technocratic government were qualified professionals, they nevertheless represented a sort of acquisition of NGOs. Cioloș explicitly sought to create a non-partisan administration and, to do so, selected figures from the NGO world. Some members of his administration had links to organisations financed by Soros. A case in point concerns Guseth’s appointment to the Ministry of Justice, a key position since Macovei was appointed in 2004. However, Guseth had no formal legal experience and was known for her activism, but when Parliament rejected her nomination, Cioloș replaced her with Raluca Prună, who had studied at Soros’ CEU and had worked with Transparency International, another NGO funded by OSF, although her impartiality in corruption rankings has been questioned.

Although Cioloș’s technocratic administration was an attempt to run Romania with competence and professionalism, Romanian democracy seemed to be stagnating. Some NGO activists had in fact aimed to gain permanent political power, creating the Save Romania Union (USR) party in 2016, which had evolved from their experience in protests and NGOs. Nicuşor Dan had transformed his Save Bucharest Association (ASB) into the Save Bucharest Union (USB) and had run for mayor in 2015. The USB then merged with other anti-establishment groups to become the third largest party in the 2016 parliamentary elections. However, the social liberalism proposed by the USR, similar to that of the NGOs linked to Soros, did not resonate well with most Romanians, which also led to Dan’s resignation as president of the USR in 2017.

In 2014, Soros stopped providing direct funding to his Romanian foundation, stating that Romanian democracy was now mature and able to support itself. In 2017, the Foundation for an Open Society officially ceased its activities in Romania, while the Serrendino Foundation, which had collaborated with the FSD, absorbed most of its staff, marking the end of a period of strong influence of Soros-funded NGOs in the country.

Between 1990 and 2014, Soros invested over $160 million in Romania, not counting the additional millions through the CEE Trust. When adjusted for Romania’s GDP, this sum would be equivalent to almost $3.6 billion in 2017.

Soros’ philosopher-hero, Karl Popper, advocated an open society in which individuals could flourish without government interference. Soros, however, prioritises the concept of an open society over the individual, arguing that an open society can also be threatened by excessive individualism. Soros’ actions in Romania show how his version of an open society threatens individual rights, national sovereignty and democracy.