Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The United State in particular, but also the United Kingdom, have shown a penchant for helping puppet leaders cling to power since the end of World War II. Zelensky is just the latest in a long list.

Great powers going back over the centuries have worked hard to install compliant leaders in other, weaker states, often with the intention of preventing a bigger rival gaining a foothold.

Zelensky wasn’t necessarily installed by western governments. The project to recreate Ukraine in a western liberal clothing had already started in February 2014 with the overthrow of former President Viktor Yanukovych. Pliable president Petro Poroshenko was as warmly welcomed in western capitals as Zelensky has been since 2022. After his election in 2019, there were serious questions in the UK government about whether to take Zelensky seriously as a political player. He didn’t stamp down on endemic corruption, as he’d promised. He wasn’t any more democratic or more liberal than his predecessors in the role.

That changed radically when war started in Ukraine in February 2022. As one commentator put it war cast aside the dark clouds over Zelensky and allowed him to pivot into a manufactured role as the ‘heroic wartime president and global symbol of defender of the free world’. Certainly, for the first six months of the war, that image worked well for Zelensky and he has an enduring appeal even today among western political figures and in the mainstream media.

But as time has gone by, Zelensky has revealed himself as having feet of clay. He is not obviously a democratically minded liberal, having been unelected since March 2024 when Presidential elections were meant to take place.

His government appears just as corrupt as every other Ukrainian government since the downfall of the Soviet Union. A poll in 2023 suggested that 77% of surveyed Ukrainians saw Zelensky as responsible for corruption.

He has known for a year and a half that Ukraine could not win a war against Russia, a realisation that sparked the sacking of popular ex-Military chief Valeriy Zaluzhniy when he pointed this out in a widely reported interview.

And yet Zelensky has done everything in his power to continue the war, to press gang western states to offer more war fighting support and to maintain an immovable objection to engaging in direct talks with Russia to end the fighting.

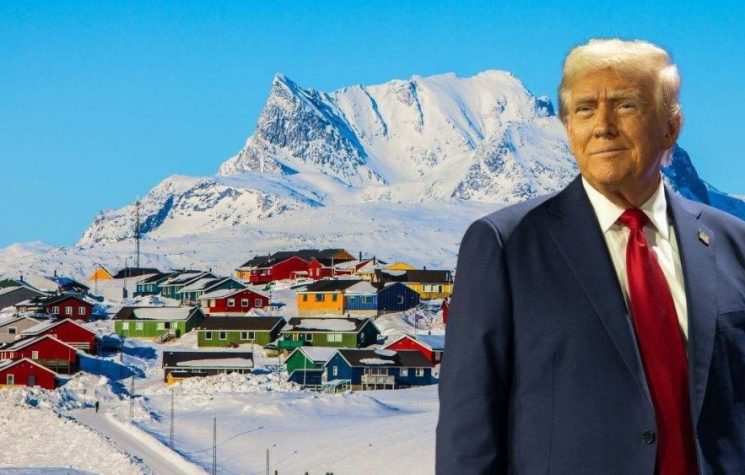

With Trump now in power, Zelensky has in recent days tried to finesse and walk back his position on talks. However, to many impartial outside observers, the reason behind Zelensky’s position can only have been driven by two considerations.

A wilful hope that NATO may eventually be drawn into a fight with Russia that Ukraine can’t win on its own.

A belief that, even without NATO intervention, western powers will continue to prop up his government with external aid.

As NATO has at no time looked remotely likely to join the fight against Russia directly, that leaves Zelensky looking like yet another puppet leader who will do anything to cling to power, until he is abandoned by his western sponsors.

Puppet leadership is a lucrative business. Your country will receive billions of dollars in aid from those countries that sponsor your existence. Your every word will be clung to by journalists from sponsoring countries, desperate to believe you are the second coming of Christ in liberal democratic white robes. Crowds will gather to applaud you and stare in wonderment at your awesomeness when you visit their countries. As you are a friend, you won’t be criticised for corruption and bad leadership, in the way that enemies are so criticized. The main problem is that you are dispensable, and when your time is up, you will either be exiled, sidelined, jailed or assassinated.

Let’s look at some examples.

Nguyen Van Thieu was the former Army officer who rose to power in South Vietnam after the CIA-back coup that toppled Ngo Dinh Diemh in 1963. Serving as President from 1967 until 1975, shortly before North Vietnam’s capture of Saigon, his most notable achievement was in overseeing a government of monumental corruption. Even in the 1960s and 70s, the small country received an average of $1.5bn each year from the U.S., around 15% of its GDP. Much of that was pocketed by corrupt officials in Thieu’s government. But he said what the Americans wanted to hear and held up South Vietnam as a bulwark against the communist north. Until it became clear that the U.S. didn’t have the political will at home, nor the military skill in theatre to beat North Vietnam, whereupon Thieu fled the scene and established himself in opulent exile in Taipei.

Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan is a more modern manifestation of the U.S.-imposed puppet leader, after his ascent to become President of Afghanistan in 2002 following the Taleban’s defeat. Of course, Afghanistan has a modern history of modern superpowers installing puppet regimes, and this was also true of the Soviet Union’s installation of Mohammed Najibullah in 1986, after a bloodless coup. Widely hailed as Afghanistan’s saviour by the western media and politicians, Karzai oversaw a government characterised by unprecedented levels of graft and corruption. Afghanistan received billions of dollars in western handouts that it was not able to absorb as a result of which, according to the Washington Post, about ‘forty percent of the money ended up in the hands of insurgents, criminal syndicates or corrupt Afghan officials’. Karzai was toppled in elections in 2014 and is now a largely forgotten figure in the annals of western puppet theatre.

While not a puppet leader in the conventional sense, Aung San Suu Kyi of Myanmar is a classic example of a foreign opposition type figure lionised by western, particularly British, diplomats, given the historical colonial link to the country formerly called Burma. Educated in Oxford, married to a brit (now deceased) she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990 for winning an election in Myanmar that was promptly stamped out by the military. When I joined the UK diplomatic service in 1999, the South East Asia Department headed fixated on her wellbeing constantly, seeing her as the only true leader of her country. Having spent years under house arrest, Aung San Suu Kyi finally won a landslide general election in 2015. She visited the UK in 2016, and I joined hordes of adoring British diplomats greeting her in the grand colonial quadrangle of the Durbar Court in King Charles Street. Softly spoken with a demure elegance, she was Prime Minister of Myanmar during an alleged genocide against Muslim Rohingyas in the west of the country, staunchly defending her military’s actions. She is now under house arrest having been convicted of possibly trumped up charges of corruption by the still powerful military and may never be free again. But western adoration has faded, and she seldom makes it into the UK media.

Benazir Bhutto, beautiful, glamorous, Harvard and Oxford educated Prime Minister of Pakistan twice in the Eighties and Nineties, was known by the UK Foreign Office to be woefully corrupt. And yet she was feted as a global superstar of western liberal democratic values because she spoke our language. Her assassination by suicide bomber in 2007 silenced lingering questions about her legacy. Although her husband Asif Ali Zardari – about whom the UK Foreign Office harboured grave misgivings about alleged corruption – is the President of Pakistan right now.

It is clear today that Volodymyr Zelensky only remains in power with the support of western nations that prop up his exorbitant and unwinnable war. When that ends, as it surely will, history suggests that he will face the same fate of those puppets that came before him; either exiled, sidelined, imprisoned or assassinated.