The microchip war continues and may soon take a new direction. Many of the geopolitically significant events of 20225 and beyond will depend on it.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The microchip war continues and may soon take a new direction. Many of the geopolitically significant events of 20225 and beyond will depend on it.

TSMC chips on the rise as planned by the U.S.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) quarterly sales exceeded estimates, reinforcing investors’ hopes that the sustained pace of spending on artificial intelligence (AI) hardware will continue through 2025. There is talk of a 39 percent increase in revenues between October and December.

The growth race in the microchip market is mainly related to the development and massive use of artificial intelligence in virtually everything. The world’s largest contract manufacturer of advanced chips has been one of the biggest beneficiaries of a global race to develop artificial intelligence, so much so that it has set itself a record of 30 percent annual growth.

Impossible? TSMC’s market value nearly doubled in 2024 and is now trading in the United States at a valuation close to $1.1 trillion. The trouble is when the AI fad will end. Problems such as overproduction and difficulty in sourcing materials (rare earths first and foremost) confront the fact that the production and sustenance of AIs are terribly energy-intensive processes. They consume so much, they are not “green” at all. But this is not well told in the mainstream press. What’s more, another problem is arising: AI Killer apps and software, a new type of programs capable of “killing” AIs, ruining them at various levels-devices, networks, servers-succeeding in significantly damaging the use of these new digital technologies.

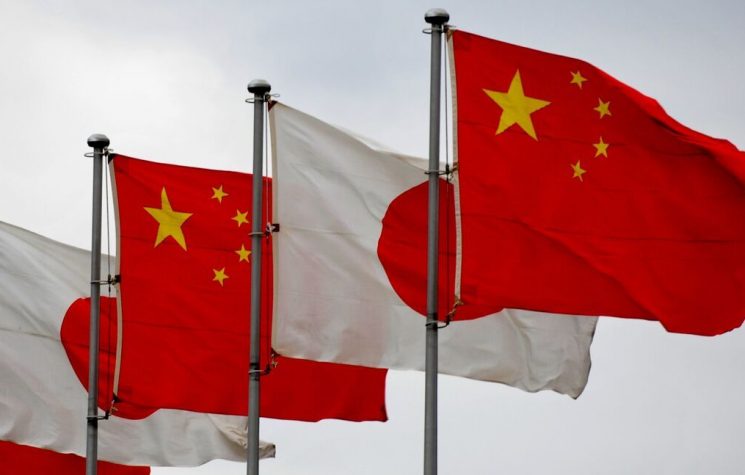

The U.S. has also set up a series of restrictions to limit the flow of Nvidia’s most powerful chips to China, with uncertain long-term consequences for TSMC’s main customer. Morgan Stanley predicts that the company will project annual sales growth of just under 20 percent in dollar terms, because it is struggling to keep up the sales trend right now anyway, especially with Apple struggling to sell its flagship products and Nvidia being put in check.

Huang delivers the coup de grace

Nice things Qbit computers, too bad we are not yet able to make their enormous potential active.

It just so happened that Jansen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, a leading company in the market, slammed the shares of the quantum sector on Wall Street, declaring that the practical use of this technology will presumably be possible only in two decades. This was a cold shower for an industry that appeared to be poised to take off in a surge but is apparently subject to the laws of the market and the laws of research far more than we think.

Shares of Rigetti Computing and Quantum Computing each fell more than 17 percent in pre-bell trading, while IonQ and D-Wave Quantum dropped 9.4 percent and 14 percent, respectively. A $3 billion loss in market value.

Shares of all the companies rose at least threefold last year, driven by a high-profile turnaround at Alphabet-owned Google and growing computing needs from generative artificial intelligence applications.

In December, Google had unveiled a next-generation chip that the company said would solve in five minutes a computing problem that would have taken a classical computer longer than the entire history of the universe, triggering a rise in its stock price.

In April 2024, Microsoft and Quantinuum said they had taken a major step in making quantum computers a commercial reality, but they did not comment on how many more years it would take to beat a conventional supercomputer using this technology.

So it took Huang to bring things back to reality. It is curious that the CEO of one of the world’s largest companies decided to inflict such a self-goal on himself at the expense of his own financial interests. Perhaps a false flag? A market disorientation strategy? It is not yet clear. What is certain, however, is that the abrupt halt has led to a shift in the stock markets that makes one think a lot about the real timetable for having these quantum technologies available.

Europe as a land to be colonized

If things aren’t working in the U.S. and it’s getting too inconvenient in Taiwan, we might as well set our sights on Europe. This is how the Americans plan to “solve” their problem.

TSMC plans to open new plants in Europe. Similarly did Intel, which plans new plants in Magdeburg, Germany, disrupting investments previously made in Poland. Without these projects, worth 30 billion euros, it is impossible to supply the European Union with enough semiconductors, shortages of which are already forcing factories to close. Previously, Intel had quietly shut down smaller-scale projects in France and Italy.

The problem is that now the European Union’s chances of competing in the global chip race have become even worse. The United States, China, South Korea, and in general everyone who can, are actively developing the semiconductor industry and handing out subsidies to attract technologies and manufacturers, while Europe has not yet set up a truly fertile ground for importing and enhancing this type of industry. Especially in the numbers and timing of production that the U.S. needs.

According to the European Chips Act, the EU planned to occupy 20 percent of the global microchip market by 2030, up from 9 percent in 2022. Now, after Intel’s departure, the share will drop from 9% to about 7-8%, because the only thing left in Europe are small TSMC subsidiaries focused on highly specialized sectors of the automotive industry.

Then there is another problem in Europe: energy costs too much. Producing microchips, we have already said, requires a lot of energy indeed. So keeping production in Europe only makes sense from the American perspective of selling to Europe. Sort of a zero-mile production-sale-consumption cycle.

Keep in mind that in the world only the companies Intel, Samsung, Hynix and Micron can design and produce the microchips themselves. All others need at least one pass through another specialized company, such as Nvidia, AMD, Qualcomm or Marvell.

Russia is safe, despite the risks

The Russian Federation is slightly behind on the autonomy side. It still needs outside suppliers, buying from China and India.

India’s exports to Russia of items such as microchips, circuit boards, and machine tools reached $60 million in April and May 2024, a record high, about twice as much as in previous months, and jumped to $95 million in July. Only China surpasses India in this area.

In 2024, Russia imported more than $1 billion worth of advanced chips from the U.S. and Europe, circumventing sanctions.

More than half of the semiconductors and integrated circuits imported in the first nine months of 2023 were produced by U.S. and European companies. These include Intel Corp., Advanced Micro Devices and Analog Devices Inc. and European brands Infineon Technologies AG, STMicroelectronics NV and NXP Semiconductors NV. The companies, however, said they were fully compliant with the sanctions, had stopped doing business in Russia at the start of the war, and had processes and policies in place to monitor compliance. This has allowed Russia to continue producing tanks and other weapons.

According to a recent report published by Kept, the Russian microelectronics market is expected to grow by 15.2 percent through 2030. The main driver of growth is expected to be government support in the form of subsidies, loans and other incentives. Russia’s current microelectronics industry has been built virtually from scratch since the beginning of 2010. The Soviet-era microelectronics industry collapsed in the early 1990s, unable to compete with international manufacturers when the country opened up to global imports. For nearly two decades, imports accounted for virtually all of the country’s microchip needs.

Today Russia has three plants capable of producing microchips on a large scale, namely those of Mikron, Angstrem and Milandr, all located in Zelenograd, near Moscow, but with reduced production capacities and only for certain types of microchips.

Positive as these figures are, however, one needs to wonder how much longer it will be possible for Russia to make all its systems dependent on microchips that are manufactured and owned by American and Taiwanese companies. This is a very high risk, which also casts shadows and doubts on agreements made in past decades, including during the Soviet period.

To conclude, an “Italian-style” curiosity: in 2024, the famous Parmigiano Reggiano cheese was equipped with a silicon microchip, the size of a grain of salt, inserted into the rind of 120,000 Parmigiano cheese wheels. The chip is manufactured by Chicago-based p-Chip, a company specializing in microtransponders. The news was commented on more abroad than in Italy, where it was virtually hidden. Well, in late August 2024, Bill Eibon, a chemist from Ohio, ate the microchip “without recording any side effects.” Digesting the microchip war will not be easy, even if it is a bit of Parmesan cheese to put on a plate of pasta.