Almost eleven years on from the introduction of the first sanctions against Russia in February 2014, Russia is growing healthily.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Russia is the most sanctioned country on the planet, with more than 20,000 sanctions imposed so far. But almost eleven years on from the introduction of the first sanctions against Russia in February 2014, Russia is growing healthily, despite a costly ongoing war in Ukraine. Let’s assess why sanctions failed against Russia.

First, economically, sanctions have never had as much impact as other globally significant economic events. They include the November 2014 and January 2016 oil price collapses, both of which had a major impact in three key areas. Russian government finances were hit by reduced revenue from oil and exports because the fall in the value of the rouble was not of sufficient depth to cushion the blow (until late 2016 when Russian monetary policy shifted). Inflation and interest rates rose sharply as the cost of imports increased in response to the devaluation. All three, reduced government income, higher inflation and interest rates bore down on domestic consumption and investment. By late 2015, while I was stationed in Moscow, I assessed that western sanctions imposed in 2014 contributed no more than 30% to the contraction in Russian growth, compared to the impact of the oil price collapse. Sanctions impacted flows of foreign capital, in particular. But as Russia weaned itself off of western capital the sanctions impact fell over time. And, of course, the economic impact of COVID vastly exceeded everything else.

Second, Russia has had a very effective top team dealing with economic issues. The combination of Elvira Nabiullina as Central Bank Governor and Anton Siluanov, as Finance Minister, has given Russia unparalleled stability in economic and monetary decision making. At key moments, being December 2014, January 2016 and February 2022, they have adjusted Russian policy to deal with external economic shocks. After the end of peak oil in 2014 Nabiullina signalled a cardinal shift away from maintaining a steady rouble to a floating rate of exchange. In 2016, monetary policy shifted towards maintaining a weak rouble to guarantee a high rouble price on oil and gas exports, whatever the price of commodities; when commodity prices rise, like, after the onset of war in 2022, Russian state finances get a double boost.

Western commentators nonetheless cheer whenever the Rouble weakens!

Floating around 100 to the dollar today, the rouble is three times less valuable than it was in early 2014. Interest rates are used to manage inflation risk and foreign exchange reserves are carefully protected. Between the end of 2014 and the start of 2022, Russia had increased its international reserves by 64% or $245bn, putting itself in a stronger position than it had been before the oil price collapse in 2014. This was only possible with effective economic leadership.

Third, sanctions have stimulated a growth in economic self-sufficiency, in particular in domestic industry and in the agriculture sector. The emergence of Rostec as a single state conglomerate to oversee strategic industrial production, including military, has undoubtedly given Russia a supply chain edge against western manufacturers that can’t produce enough artillery shells. In the agriculture sector, Russian counter-sanctions in August 2014 and drive to import substitution precipitated a surge in domestic food production. One bi-product of this was the stimulation of metropolitan food culture through the renovation of old markets and consequent artisan pop-up culture (I can recommend the locally produced burrata and steaks). Yes, Russia’s economy is still over-reliant on revenue from mineral exports. But why would any economy give up that comparative advantage at a time of significant economic risk?

Finally, if sanctions are a political weapon by economic means, then Russian leaders always saw them as unjustified and illegal, and, as a result, refused to back down in the face of western pressure. The economic consequences of sanctions have always been subordinate to their ability to change political decision making in Moscow. And on that, they have failed catastrophically.

The west actively sponsored an unconstitutional change of power in Kiev in February 2014 (tactics they are trying to repeat in Georgia today) and installed a nationalist government with an antagonistic attitude towards Russia. Whether you consider Russia’s subsequent actions to have been justified in Crimea and the Donbas, it would have been an act of political suicide for President Putin, then, to backdown in the face of the wave of western sanctions. In fact, sanctions have had the opposite political effect, by driving a growth in the BRICS grouping (which has included anti-sanctions language in its communiques since 2014) and a shift towards alternative global financial systems.

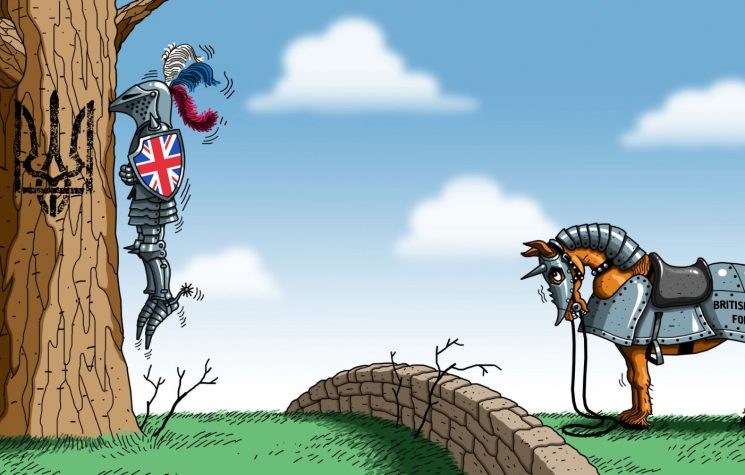

It is striking with the war soon to hit the three year mark, and with Ukraine slowly losing on the battlefield, that many commentators in the west still push for more sanctions, rather than a negotiated end to fighting.

Many are taking aim at the $300bn in frozen Russian assets, most of which sit in Euroclear in Belgium. While the EU has been willing to take the legally questionable move of using the profits from those frozen assets to fund a G7 loan package (as western nations have now stopped giving Ukraine anything for free), it has shied away from full confiscation. The economic and political risks are obvious. Economically, the theft of assets would strike a blow to the credibility of Europe’s financial system at a time when its two largest states – France and Germany – are in the midst of political and economic crises. Politically, it would incentivise Russia to continue the war in Ukraine; why would Russia sign up to a ceasefire in circumstances where assets valued at 150% of Ukraine’s entire economy were seized? So, despite pressure from the U.S. and the UK, I judge the EU won’t take the risk and, in any case, Hungary and Slovakia would seem almost certain to block the move.

Failure to steal the frozen assets in their entirety doesn’t leave much on the table for the west to sanction. And on the basis that the western alliance has imposed it biggest sanctions already, it’s unlikely that additional sanctions would have any impact anyway.