Contrary to what happens in fascism, under which working class organizations are crushed, in Egypt’s nationalist regime mass movements were not suppressed, but to a large extent protected, Eduardo Vasco writes.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

With the outbreak of the Second World War, in Arab countries (colonized by the Allied powers, England and France) some governments and movements, mostly for pragmatic reasons, supported the Nazi-fascist Axis forces.

Among them were nationalist groups who, when not remaining neutral, sought to ally with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy to defeat the British and French occupying forces. On the other hand, most communist parties – influenced by Stalinist politics – campaigned for enlistment in the colonial army.

Hence, the idea that Arab nationalism would have fascist inspirations. And, nationalism, in general, would also have fascist characteristics, as the case of Getúlio Vargas in Brazil during the Estado Novo or Juan Domingo Perón in Argentina.

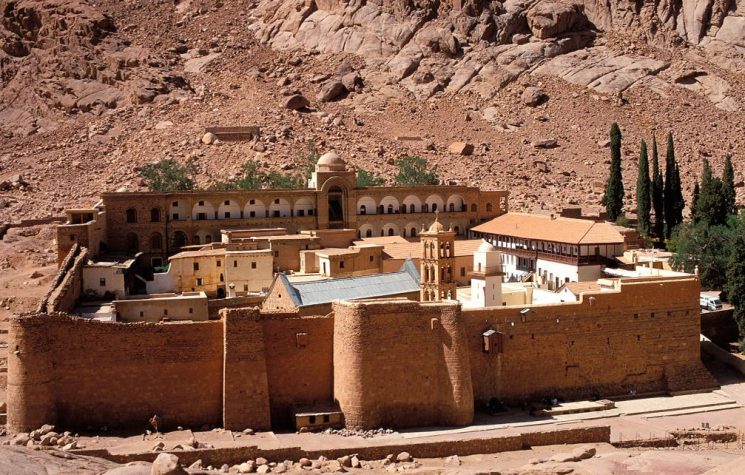

Another alleged fascist characteristic of Arab nationalism, particularly that of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s government, would be the corporatist political and social regime. The Republic, proclaimed in 1953, abolished political parties, unions were placed under government control and workers lost their class independence, with the persecution of opposition unionists. The repression of communists was strong in the first years of the revolution, with the closure of the communist party. After Egypt’s rapprochement with the USSR, the regime allowed the creation of a new communist party, which later ended up fully integrated with Nasserism.

Furthermore, the Muslim Brotherhood, a radical religious mass movement, was violently persecuted from 1954 onwards. Linguistic and national minorities were discriminated against by the revolutionary system.

The Egyptian constitution created in 1956 subordinated the National Assembly to the president, Nasser. The Charter also established a single party, the National Union. In turn, the 1961 National Charter set up a corporatist National Congress of Popular Forces, in which its members were not chosen through free debate, and popular organizations were controlled by the government.

However, despite corporatism and control of popular organizations, the Nasserist revolution allowed and encouraged the occupation of various positions by mass movements, and the Arab Socialist Union – later name of the National Union, with the adoption of the 1961 Charter – proposed the allocation of half of the vacancies in political organizations and in the Chamber of Deputies to workers and peasants. A series of reforms also improved the living and working conditions of the popular classes and allowed some participation in company management, something that had never been considered by the dictatorships of Mussolini and Hitler.

Contrary to what happens in fascism, under which working class organizations are crushed, in Egypt’s nationalist regime mass movements were not suppressed, but to a large extent protected. It can be said that Nasserism was more akin to conciliation with the workers’ movement (which had been strong since the Revolution), seeking to prevent its independence, rather than combating it, as traditionally occurs in a fascist regime.

Another common feature of fascist regimes (such as those in Germany, Italy or the Apartheid’s South Africa and Israel) is extreme racism. Despite the contradictions of his regime, Nasser’s pan-Arabism did not mean the submission of other peoples by “Great Egypt”, as German and Italian expansionists preached about their respective states – and as Israel does.

“Our resistance to racial discrimination expresses a clear understanding of the true meaning of the problem. Racial discrimination is a form of foreign exploitation of people’s wealth and work. The slavery regime, based on racial discrimination, was the first form of imperialist exploitation. Racial discrimination is violence against universal conscience,” Nasser wrote.

Nasser, like the Nazi-fascist regimes (and like most capitalist regimes, as a whole, depending on the forces relation between the workers and the capitalists), sought to neutralize the contradictions of the class struggle: “The inevitable and natural class struggles cannot be ignored or denied, but their solutions must be achieved peacefully, within the framework of national union, through the dissolution of distinction between classes.” However, the difference between the policy adopted by his regime and that adopted by Nazi fascism is visible: while this was used by the German and Italian imperialist bourgeoisie to crush the working class and place it under its total control, greatly benefiting capital, the Nasserist regime was supported by the working masses, in a conciliation with the bourgeoisie and, to a certain extent, with imperialism, making concessions to the workers to guarantee the dominance of the capitalists and trying to curb their more radical positions, not crushing them with the force of the State as was made in Germany and Italy.

Still, the nationalist discourse of fascism, which is pure rhetoric, is not true nationalism. The German and Italian fascist regimes were controlled by the imperialist bourgeoisie of their countries to exploit their people and other peoples, guaranteeing the enjoyment of national wealth by capitalists and not by the people. Nationalism is not the same thing in a backward country and in a developed country. In a developed country, nationalism is the defense of that country’s imperialism, while in a backward country it is the fight against imperialism, although, to a certain extent, it invariably makes some type of conciliation with imperialism, by representing the interests of the fragile national bourgeoisie of a given country. When the nationalist regime, due to the interests of the bourgeoisie, moves closer to imperialism, it moves to the right; when, on the other hand, the interests of the bourgeoisie are the same as national interests and the regime clashes with imperialism, it is displaced to the left of the political spectrum.