❗️Join us on Telegram ![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK ![]() .

.

Notes on context, editing, and translation:

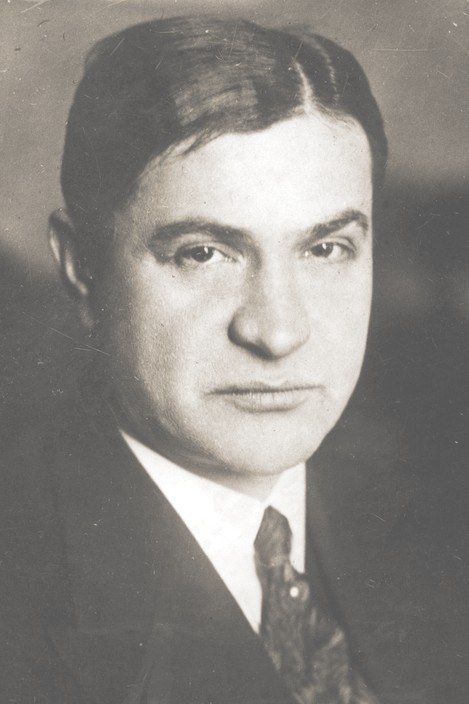

The original article was entitled “Stories from Oles Buzina: Bandera—the Cat Strangler” written by a prominent Ukrainian journalist Oles Buzina and published on January 29, 2010. Buzina was a Ukrainian patriot who believed Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarussians were triune. He was critical of the gradual imposition of the minority Galician (western Ukrainian) identity onto the majority of Ukraine even before the 2014 Maidan. For example, in this article, the author criticizes Ukraine’s former President Viktor Yushchenko brought to power through the so-called Orange Revolution in 2004. Some consider the 2004 event to be a proto-regime change in that country that succeeded in 2014. In 2010, Yushchenko posthumously granted Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera the Hero of Ukraine title. Bandera lived in Polish-controlled Galicia outside the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the 1920s-1930s and then in Munich, Germany. The latter is an early negative-identity example along the same trajectory as the post-2014 attempts to “cancel” the Russian language and heritage and even remove monuments to the Soviet WWII military leaders.

«Any politician who tries to impose Bandera as Ukraine’s hero will not only destroy his personal career…but will also destroy the country.»

OLES BUZINA, IN “UNHEROIC ‘BANDERA’,” JANUARY 2011

In April 2015, Buzina was assassinated outside his Kiev home—allegedly for his vocal criticism of the Maidan. The murder was one of the first key signs of political radicalization in Ukraine. I have previously translated him here.

The article is presented in its entirety. The only deviation from the original is using the first name the first time each new individual is mentioned. Square brackets are editorial clarifications.

Stepan Bandera—the Cat Strangler

by Oles Buzina

It’s too bad that [Ukraine’s President (2005-2010)] Viktor Yushchenko doesn’t know history very well. With his decree making Stepan Bandera a national hero [of Ukraine], he spat in the soul of animal rights advocates all around the world by awarding an animal abuser.

As a writer, what impresses me the most in the story of the newly minted “hero of Ukraine,” is the completeness of the gastronomical theme. On Bandera’s order in 1934, the Interior Minister of Poland, Bronisław Pieracki, was assassinated as he entered a cafe in Warsaw to grab a bite to eat. The mastermind and organizer of this “attentat” (what they call assassination attempts in Galicia [Ukraine]), the half-educated student Bandera was only 25 years old. He was halfway through his life path which he did not suspect.

Exactly twenty-five years later, the situation will mirror itself. In this case, it is Bandera who will carry a bag of freshly purchased tomatoes in his hands and climb the stairs toward the door of his Munich apartment. He, too, was going to make a salad and have a delicious lunch. But his death was already descending from above embodied by a young man with a pistol loaded with a special poisonous substance that causes instant heart paralysis. In just a second, Bandera will roll down the stairs without having any time to dine just like Minister Pieracki.

Another coincidence is that both Pieracki’s assassin Grigory [Hryhorij] Maciejko and Bandera’s killer Bogdan Stashinsky were both Galicians. The circle is closed again! But the most surprising thing is that Maciejko did not want to kill Pieracki, and Stashinsky did not want to kill Bandera. Bandera forced Maciejko to carry out a terrorist act. Otherwise, his friends in the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, OUN, themselves threatened to destroy him. And Stashinsky, as he later claimed, became a KGB agent, after having been caught for a petty crime—somehow he decided to ride public transportation without paying for a ticket and got caught by the ticket controller. In the 1940s, he faced being expelled from his university for this incident, and he agreed to first rat people out and then eliminate them.

But, what is most surprising, is that both Maciejko and Stashinsky broke the dependency cycle on the “parent” organizations in exactly the same way. The former emigrated to Argentina, breaking with the OUN, and the latter, having said “goodbye” to the KGB, disappeared somewhere in the West and lived (or, perhaps, is still living) under a different surname in complete obscurity.

I will refrain from analyzing whether Nikita Khrushchev should have ordered the Soviet intelligence agencies to liquidate Bandera in order to turn a killer into a victim even at the end of his life. I will only note the following: the end of the “OUN guide” is quite typical for any major terrorist. Those who belonged to the [19th-century Russian left-wing revolutionary, terrorist organization] People’s Will, the Socialist-Revolutionary Boris Savinkov, and [Russian statesman Pyotr] Stolypin’s murderer Dmitry Bogrov ended their lives in exactly the same way. At first, they “took out” major political figures themselves. Then they were the ones who were eliminated in order to posthumously become “heroes.”

The end of the Ukrainian nationalist leaders and other characters from the period of great terror differs only in that their death was surprisingly similar to the end of the criminal organization leaders of the 1990s. They were eliminated when, having drunk enough blood, they became almost decent people and started thinking about the ways of spending their retirement comfortably. But their old sins would not allow this! As soon as Bandera’s predecessor as the head of the OUN, Yevgeny [Yevhen] Konovalets, had come into money and happy life in Europe, it was then that he was helpfully delivered in Rotterdam a box of chocolates with a bomb built into it. Symon Petliura, who had disappeared from Ukraine along with the state treasury (let the man enjoy his life!), had barely gotten used to his relaxing walks around Paris, and Sholom Schwartzbard had already jumped in front of him with his revolver. Doesn’t all this remind you of the deaths of Kiev’s criminal [gangster-businessmen] “authorities”—who usually ended up on a short path between their apartment and a recently parked car—obtained through backbreaking criminal gang labor?

Whether you like it or not, Viktor Yushchenko, who once promised prison terms to bandits, posthumously picked out a hero’s star from the state’s “shared fund” precisely for a bandit. A political one, however. But this does not change the essence of the matter because Bandera’s activities were reduced to the extraction of financial gain by using run-of-the-mill robbery. And the fact that he personally did not kill anyone at that time does not excuse the never-to-be-forgotten dead man. He was only unable to do so considering his poor health, crooked legs, osteomalacia he suffered in his childhood, and an overall not particularly masculine, frankly speaking, physique. Pan [Polish “Mister”] Bandera’s height at the peak of his physical development and political career was only 159 cm [5 feet 2 inches]. So, with such athletic characteristics, the future “hero of Ukraine” could only…strange cats with his bare hands.

And he loved strangling cats! Just like Mikhail Bulgakov’s Sharikov [in the Heart of a Dog]! It was his favorite childhood activity like watching cartoons for other children. He honed his willpower and ruthlessness towards the enemies of the nation by using cats! Moreover, little Stepan strangled them in public—in front of his peers—instilling in them terror and respect for his short, but formidable persona. Even his present-day, supportive biographers do not deny this fact.

In 2001, a certain Galina Gordasevich wrote a book called Stepan Bandera—the Man and the Myth [Liudina i mif] published by the Library of Ukraine [Biblioteka ukraintsia] series. This lady loves her hero so much but explains the episodes with his mass killing of cats in a unique way:

«If the episode with the cats really took place, then it was not from an innate tendency to sadism, but from a boyish, perhaps, even unreasonable desire to test oneself: can you take the life of another creature? After all, in the revolutionary struggle that Stepan Bandera had finally chosen for himself, one will probably have to take the lives of enemies and traitors…»

Good Lord, why cats? Are they also agents of the NKVD, members of the Communist Party, traitors to the “national cause,” and relatives of the Minister of Internal Affairs of Poland? Do as you wish, but I cannot understand this. This is the case of clear-cut sadism, which has developed with age into practical politics expressed in the 17th point of the “44 Rules for Life of a Ukrainian Nationalist”:

«Treat your enemies as the good and greatness of your Nation require.»

The phrasing is very grandiose. Yet it is not clear who the enemies of the nation are, and who said that it is they who are precisely the kind of enemies that are required. Indeed, the phrasing is so vague that the enemies of Bandera—who always mistook himself for the nation—turned out to be the Poles, the “Soviets,” and the Ukrainians, who did not want to see him as their own home-grown Führer, and, ultimately, his very own nationalist competitors. They all fit the “enemy” definition. Everyone was to be strangled just like those cats displaying the “greatness of spirit.”

During his entire fifty-year-long life, Stepan Bandera had never worked anywhere. However, as a child, he helped out his family with the housework. He also wrote humorous feuilletons in the underground party press by using the pseudonym Gordon. He studied at the Politechnika Lwowska as a crop scientist—naturally, his family paid for his studies. It was his grandfather who helped the most. But he did not graduate from the Politechnika because he became interested in organizing raids and assassination attempts. Either they “bombed” the post office in Gorodok [Grodek (Polish), Horodok (Ukrainian)], or they killed the school teachers. Some—Ukrainians—because, in Bandera’s view, they were pro-Polish. Others—the Poles—for agreeing with the need to teach the Ukrainian language in school. So, according to Bandera’s perverted logic, they contributed to improving the relations between the Poles and Ukrainians.

«Our government,» Pieracki stated, «is guided by the intention of creating the rational grounds for the harmonious coexistence of all citizens of Poland based on equal rights and responsibilities for all.»

This is why Bandera killed him. After all, he did not need a “harmonious coexistence.” He needed himself, Bandera, to lead Ukraine. By the way, this OUN leader had never even seen Ukraine. Ukraine existed abroad—in the USSR. He, however, lived in Galicia, which was then officially called Małopolska Wschodnia (Eastern Lesser Poland). Ukraine existed for him more as a compensatory idea designed to distract him from the boredom of daily student life with exams and the prospect of becoming a crop scientist in his native village.

He did not have to worry about sustenance after the Polish Themis gave Bandera a life sentence after investigating the murder of Pieracki. He would be fed and clothed in prison. It’s true, however, that the sadistic Poles subtly mocked the “hero” by not allowing him to strangle cats. For this reason, this outstanding man suffered terribly. But Adolf Hitler came to the rescue. In 1939, he captured Poland, released Bandera from prison, and hired him. Following the instructions of the Abwehr—the Germans’ military intelligence—Banderites formed two battalions, Nachtigall and Roland. These units were intended for engaging in punitive actions on the territory of the USSR. The former became famous for the 1941 pogrom of the Poles in Lvov.

The second time Hitler saved Bandera was in 1944: he did not allow him to be captured by the Soviet troops. The hero of Yushchenko’s dreams was personally transported out of the besieged Krakow by Otto Skorzeny, the famous saboteur who kidnapped the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini from under arrest. This episode shows how much the Führer valued his little Ukrainian “friend”—probably no less than George W. Bush once valued Yushchenko. It is possible that the latter will also fly out of Ukraine protected by the American special forces.

Like the rest of the OUN, the Germans hand-fed Bandera. However, he did not know when to stop and sometimes pocketed their government money. Naturally, his “sponsors” did not like this at all. But for the time being, they turned a blind eye to it. The patience of German intelligence ran out in the first two weeks after the invasion of the USSR. The Germans needed the kind of OUN that would carry out their exact orders rather than killing indiscriminately left and right. Even criminals do not tolerate such thugs. And, by that time, both the Abwehr and the influential party circles of the Third Reich considered Bandera a total thug. He even initiated a massacre within the OUN itself by speaking out against its official leader Andrei [Andriy] Melnyk. The personnel he selected from the Nachtigall battalion sought to transform the German rear into an arena for their “showdown” with the Poles. Nachtigalll had to be urgently reorganized into an auxiliary police battalion [Schutzmannschaft Battalion 201] and transferred to Belarus to fight the [Soviet] partisans. In turn, Bandera first had to be taken under house arrest in Krakow and then transferred to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. But he was not taken into ordinary barracks, but to a kind of hotel where captured high-ranking officers and Nazi collaborators temporarily withdrawn into “reserve” status stayed. The official charges brought against him sound very modern: the theft of funds allocated by the German intelligence for the “development of the OUN” and transferring them into a personal account in a Swiss bank.

In 1944, Hitler took Bandera out of his “reserve” status and included him in the so-called Ukrainian National Committee—a pocket organization whose objective was to organize a fight against the advancing Red Army. Shortly before this, Bandera’s supporters, led by Roman Shukhevych, established control over the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which ended up in the rear of the advancing Soviet troops. To the best of their ability, the Germans supplied the UPA with weapons and ammunition, hoping that it would destabilize the situation in western Ukraine. To a certain extent, these hopes were justified. The German ticking time bomb will operate until the late 1950s. It was at that time that the idea to eliminate Bandera emerged in the bowels of the Soviet leadership—to show the OUN that they could no longer continue their terror—otherwise their leaders would be destroyed even outside the USSR in Western Europe. We could argue that the warning worked. After Bandera’s death, the OUN not only renounced terror tactics but also began working hard to appear as a “decent,” almost democratic organization.

By this time, the organization was already intensively supplied by U.S. intelligence. For example, on the list of intelligence information that the Americans demanded from Bandera’s and Shukhevych’s associates, there were such exotic cases as the information about the state of the air defense system in the Odessa district. As they say, where is Galicia, and where is Odessa? [That is, Galicia and Odessa are far away from each other.] And why did the UPA need the information about the air defense on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine? The UPA had no aviation. It could not bomb Odessa independently from its shelter.

Naturally, Bandera himself did not make his way to Ukraine for intelligence-gathering. He “loved” Ukraine from afar—from Munich. He went skiing in the Alps and was photographed with his family making memories. If you see his photos with children, he looks like some kind of a minor accountant, and nothing more. A very decent person! It’s just that he strangled many cats…

P.S. At least 300 thousand people fell victim to Banderite terror in the 1940s. In 1943 alone, the UPA massacred 80,000 Poles and members of Ukrainian-Polish families during the so-called Volyn [Wołyń] Massacre. Banderites carried out ethnic cleansing killing mostly defenseless civilians—both Poles and Ukrainians who refused to support Bandera’s OUN. There is no information about the “war” between the Banderites and the Wehrmacht in the German archives.