The current conflict in Ukraine shows that restoring a sense of reality exacts a heavy and bloody toll, writes Laura Ruggeri.

On March 10 when CIA director Bill Burns addressed the U.S. Senate and declared “Russia is losing the information war over Ukraine”, he repeated a claim that had already been amplified by Anglo-American media since the start of Russia’s military operations in Ukraine. Though his statement is factually true, it doesn’t tell us why and mainly reflects the West’s perspective. As usual the reality is a lot more complicated.

The U.S. information warfare capability is unparalleled: when it comes to manipulating perceptions, producing an alternate reality and weaponizing minds, the U.S. has no rivals. The U.S. coercive deployment of non-military instruments of power to bolster its hegemony, and attack any state that challenges it, is also undeniable. And that’s precisely why Russia was left with no other option than the military one to defend its interests and national security.

Hybrid warfare, and information warfare as an integral part of it, evolved into standard U.S. and NATO doctrine, but it hasn’t made military force redundant, as proxy wars demonstrate. With more limited hybrid warfare capabilities, Russia has to rely on its army to influence the outcome of a confrontation with the West that Moscow regards as an existential one. And when your existence as a nation is at risk, winning or losing the information war in the Western metaverse becomes rather irrelevant. Winning it at home and ensuring that your partners and allies understand your position and the rationale behind your actions inevitably takes precedence.

Russia’s approach to the Ukraine question is remarkably different from the West’s. As far as Russia is concerned Ukraine is not a pawn on the chessboard but rather a member of the family with whom communication has become impossible due to protracted foreign interference and influence operations. According to Andrei Ilnitsky, an advisor to the Russian Ministry of Defence, Ukraine is the territory where the Russian world lost one of the strategic battles in the cognitive war. Having lost the battle, Russia feels all the more obliged to win the war – a war to undo the damage to a country that historically has always been part of the Russian world and to prevent the same damage at home. It is rather telling that what U.S.-NATO call an “information war” is referred to as “mental’naya voina”, that is a cognitive war, by this prominent Russian strategist. Being mainly on the receiving end of information/influence operations, Russia has been studying their deleterious effects.

While it is too early to predict the trajectory of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and its political outcomes, one of the main takeaways is that the U.S. employment of all instruments of hybrid warfare to instigate and fuel this conflict, left Russia no alternative than the recourse to military power to solve it. You can’t win the battle for hearts and minds when your opponent controls them. You first need to restore the conditions that will make it possible to reach them and even then it will take years to heal wounds, undo the psychological conditioning.

Though disinformation and deception have always been a part of warfare, and information has long been used to support combat operations, within the framework of hybrid warfare information plays a central role, so much so that in the West combat is seen as taking place primarily through it and vast resources are assigned to influence operations both online and offline. In 2006 retired U.S. Maj. General Robert H. Scales explained a new combat philosophy that would later be enshrined in NATO’s doctrine: “Victory will be defined more in terms of capturing the psycho-cultural rather than the geographical high ground.”

In the U.S.-NATO lexicon, information and influence are interchangeable words. “Information comprises and aggregates numerous social, cultural, cognitive, technical, and physical attributes that act upon and impact knowledge, understanding, beliefs, world views, and, ultimately, actions of an individual, group, system, community, or organization.”

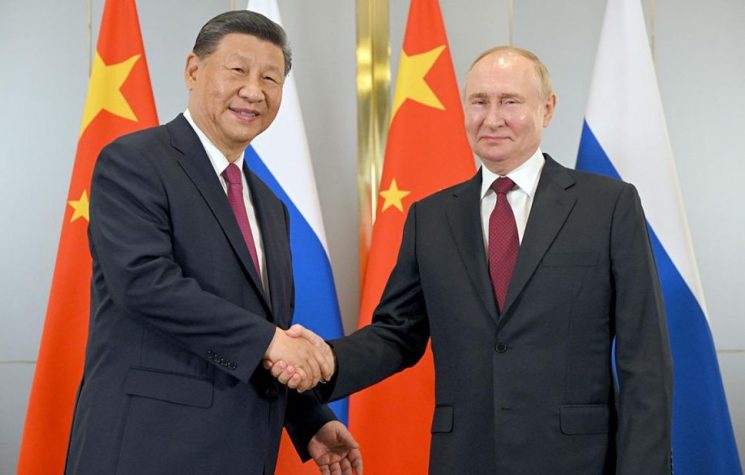

The U.S. information war arsenal is unmatched because it controls the Internet and its main gatekeepers of content such as Google, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Wikipedia… It means the U.S. can exercise control over the noosphere, that “globe-spanning realm of the mind” that RAND in 1999 was already presenting as integral to the American information strategy. For this reason no government can ignore the profound impact of the Internet on public opinion, statecraft and national sovereignty. Because neither Russia nor China can beat the U.S. in a game where it holds all the cards, the smart thing to do is to leave the gaming table, which is exactly what both powers are doing, each drawing on its specific strengths.

The “information war over Ukraine” didn’t start in response to Russia’s military operations in 2022. It was initially unleashed in Ukraine. Since 1991 the U.S. spent billions of dollars, and the EU tens of millions, to tear this country apart from Russia, not to mention the money spent by Soros’ Open Society. No price was deemed too high due to the importance of Ukraine on the geopolitical chessboard. U.S. influence operations led to two colour revolutions, the Orange Revolution (2004-05) and EuroMaidan (2013-14). After the 2014 bloody coup, with the removal of any counterweight, U.S.-NATO influence turned into full control and violent repression of dissent: those who had opposed Maidan lived in fear – the Odessa massacre being a constant reminder of the fate that would befall anyone who dared to resist the new regime.

The promotion of Neo-Nazi tendencies intensified, together with the cult of Nazi collaborationist Stepan Bandera; members of terrorist organizations such as the Azov Battalion and other ultranationalist groups joined government and the Ukranian National Guard, the past was erased and history re-written, Soviet monuments were destroyed, Russian-speakers faced daily threats and discrimination, pro-Russian parties and information outlets were banned, Russophobia was inculcated in children starting from kindergarten. In 2020 alone ultranationalist projects, such as the “Young Banderite Course”, “Banderstadt Festival of Ukrainian Spirit”, etc. received almost half of all the funds allocated by the Ukrainian government for children’s and youth organisations.

Ukrainians who lived in the separatist People’s Republics of Donetsk and Lugansk and couldn’t be targeted by influence operations were targeted by rockets, bombs and bullets: the former compatriots had been recast as enemies almost overnight. While all quality of life indicators revealed a marked decline, large segments of the population lived in a permanent state of cognitive dissonance: they were told that discriminating LGBT is wrong but discriminating Russian speakers is right, remembering Soviet soldiers who had fought Nazism in WW2 and liberated Auschwitz is wrong, remembering the Holocaust is right. Because cognitive dissonance is an uncomfortable feeling, people resorted to denial and self-deception, embraced whatever opinion was dominant in their social environment to seek relief.

Since the mindset of an entire population cannot be changed overnight, even with an army of cognitive behaviour specialists, the groundwork was laid in stages. The Orange Revolution helped foster Ukrainian national identity but precisely because it leveraged on existing cultural and linguistic differences it ended up being the most regionally divided of all colour revolutions: western Ukrainians dominated the protests and eastern Ukrainians largely opposed them. The Orange Revolution had a profound effect on the way Ukrainians perceived themselves and their national identity but it didn’t succeed in severing the political, cultural, social, and economic ties between Ukraine and Russia. Most people on both sides of the border continued to regard the two countries as inextricably intertwined.

A second revolution, Euromaidan, would finish the job started in 2004. This time the narrative had a wider appeal: its proponents identified corruption and lack of economic prospects as the main grievances of the population, indicated Ukraine’s leadership and its ties to Russia as the main cause of the country’s troubles and proposed integration into the EU as a cure-all solution.

Turning Russia into a scapegoat for all societal and economic problems, fuelling an anti-Russian sentiment was exactly what a myriad of U.S. and U.S.-funded players had been doing since the fall of the Soviet Union. Ukraine, like the rest of post-Soviet countries, was teeming with media outlets, NGOs, educators, diaspora groups, political activists, business and community leaders whose status was artificially inflated by their access to foreign resources and international networks.

These “vectors of influence” introduced themselves as purveyors of “global standards and best practices”, “democratic rules”, “participatory development and accountability”, used marketing buzzwords for their work of demolition of existing practices, frames of reference and their sostitution with new ones, often of inferior quality. Under the guise of fighting corruption, offering a path to modernization and development these players became entrenched in Ukraine’s civil society, shaped its collective consciousness and demonized both Russia, local politicians and public figures who advocated closer relations with Moscow.

The work of these agents of influence was instrumental in demolishing worldviews, beliefs, values and perceptions that dated back to Soviet times, thus altering the population’s self-understanding. It ensured that younger generations would be ignorant about their country’s history and embrace a new fictional identity.

But colour revolutions require both brain and brawn to topple governments and defend the power of the new ruling class. The brute force that was necessary to intimidate and attack those who were impervious to influence operations could only be provided by fringe elements in society who had been seduced by the ultra-nationalist rhetoric.

These violent fringe groups were organized and empowered to exercise greater influence in Ukraine and thus attract more followers. A romanticized, imaginary identity was radicalized by absurd claims that Ukrainians and Russians cannot be called brotherly nations because Ukrainians are “pure-blood Slavs”, while Russians are “mixed-blood barbarians”. Nothing was beyond the pale: sleek re-enactments of Nazi propaganda tropes like torchlight parades that looked impressive on social media, speeches that echoed Hitler’s, xenophobic and anti-Semitic rhetoric, the cult of Bandera and those who fought with the Nazis against the Soviet Army.

While foreign groups sharing the same ideological tool box were labelled extremist and terrorist organizations just across the border, in Ukraine they received advice, financial and military support by the U.S. military and the CIA. At the same time the CIA presentable spin-off, NED, was giving out funds, grants, scholarships and media awards to their globalist, politically-correct, “freedom, democracy and human rights” country fellows. The latter cohort would whitewash the crimes of the former. After all, if members of Al-Qaeda donning white helmets in Syria became the darlings of Western media and even won an Oscar, Neo-Nazis could be marketed as defenders of democracy just as easily.

Ukraine’s population was subjected to the sort of psychological operations that would make it want more of a medicine that not only didn’t cure the disease but could kill the patient. In order to turn the country into a beachhead from which to launch hostile operations aimed at weakening Russia and creating a rift between Moscow and Europe, Russophobia had to become a sort of state religion, anyone who didn’t practise it was to be marginalized and eventually excluded from public discourse. The pressure to conform was so strong that it impaired judgement.

The discursive construction of an enemy required the constant demonization of Russia (Mordor), Russians (uncivilized Eurasian barbarians) and Donbass separatists (savages, subhumans).

When neo-Nazi narratives and Russophobia are normalized and allowed to shape both policies and dominant discourse, when people are “weaned” from critical thinking, from their own history, and wage an 8-year long war against their fellow countrymen, that’s a sign people’s minds have been weaponized.

Public consciousness was actively manipulated both at the level of meaning and at the level of emotions. Selective perception and consolatory fantasies were some of the psychological mechanisms ensuring that the population would manage the stress of living in a state of cognitive dissonance where facts and fiction could no longer be separated. By offering cheap passage through a complex world, these narratives provided emotional certainty at the cost of rational understanding.

The emotionally satisfying decision to believe, to have faith, inoculated individuals against counter-arguments and inconvenient facts. The election of an actor on the basis of his convincing performance as a president in a TV series titled “Servant of the People” confirmed the successful substitution of politics with its spectacular simulation: it wasn’t simply the blurring of illusion and reality, but the authentication of illusion as more real than the real itself. The majority of Ukrainians voted for a brand new party that was named after the TV fiction and was the brainchild of the same people. A party that even used billboards advertising the series for Zelensky’s election campaign.

With the global streaming of the TV series by Netflix and its broadcasting by more than a dozen TV channels in Europe we see the marketing of Zelensky to foreign audiences as an image-object whose immediate reality is its symbolic function in a semiotic system of abstract signifiers that take on a life of their own and generate a parallel, virtual reality. This virtual reality in turn generates its own discourse.

For instance, to foreign audiences the 8-year long war in Donbass that caused 14,000 deaths is less real than images extrapolated from a videogame and passed off as “the bombing of Kiev.” That’s because the war in Donbass has been largely ignored by international media.

Images of atrocities, whether taken from other contexts or fabricated, have become free-floating signifiers that can be repurposed according to the needs of propagandists, while real atrocities must be hidden from view. After all it doesn’t matter whether the narrative is true or false, as long as it is convincing.

In post-Maidan Ukraine one could see an anticipation of the fate that awaited the rest of Europe, almost as if Ukraine had been not only a laboratory for colour revolutions, but also a testing ground for the kind of cognitive warfare operations that are leading to the rapid destruction of whatever vestige of civility, logic and rationality is left in the West.

Cognitive warfare integrates cyber, information, education, psychological, and social engineering capabilities to achieve its ends. Social media play a central role as a force multiplier and are a powerful tool for exploiting emotions and reinforcing cognitive biases. Unprecedented information volume and velocity overwhelms individual cognitive capabilities and encourages “thinking fast” (reflexively and emotionally) as opposed to “thinking slow” (rationally and judiciously). Social media also induce social proofing, wherein the individual mimics and affirms others’ actions and beliefs to fit in, thus creating echo chambers of conformism and groupthink. Shaping perceptions is all that matters; critical opinions, inconvenient truths, facts that contradict the dominant narrative can be cancelled with a click, or by tweaking the algorithm. NATO uses machine learning and pattern recognition to quickly identify the locations in which social media posts, messages, and news articles originate, the topics under discussion, sentiment and linguistic identifiers, pacing of releases, links between social media accounts etc.

Such system allows real-time monitoring and provides alerts to NATO and its social media partners, who invariably comply with its requests to remove or ‘shadow ban’ content and accounts deemed problematic.

A polarized, cognitively disoriented population is a ripe target for a type of emotional manipulation known as thought-scripting and mind-boxing. A person’s thinking comes to congeal around increasingly set scripts. And if the script is arguable, it is unlikely to be changed through argument. The well-boxed brain is impervious to information that doesn’t conform to the script and defenceless against powerful falsehoods or simplifications that it has been primed to believe. The more boxed a mind, the more polarized the political environment and public dialogue. This cognitive damage makes all efforts to promote balance and compromise unattractive, in the worst cases even impossible. The totalitarian turn of Western liberal regimes and the insular mentality of Western political elites seem to confirm this sad state of affairs.

With the ban on Russian information outlets, the exclusion and bullying of anyone who seeks to explain Russia’s position, the equivalent of ethnic cleansing of public discourse has been achieved and its cheerleaders have a mad grin on their face that doesn’t bode well.

Examples of irrational mob frenzy are too many to list, those who have fallen victims to this pseudo-religious fervour demand that Russia and Russians be cancelled. For that matter you don’t even need to be human or alive to become a target of mass hysteria: Russian cats and dogs have been banned from competitions, Russian classics banned from universities, Russian products taken off the shelves.

The relentless manipulation of people’s emotions has unleashed a dangerous whirlwind of mass insanity. As in Ukraine, so in Europe citizens are supporting decisions and calling for measures against their own interests, prosperity and future. “I’ll freeze for Ukraine!” is the new epitome of virtue-signalling among those who access only U.S.- approved information, the kind of script compatible with a frame of reference that excludes complexity. In this fictional, parallel universe, a sort of safe, reassuring, compensatory metaverse that has broken free from the messiness of reality, the West always occupies the moral high-ground.

By and large international media coverage of the war in Ukraine has been not only fictional but also completely aligned with narratives provided by Ukrainian propaganda units that were set up and funded by USAID, NED, Open Society, Pierre Omidyar Network, the European Endowment for Democracy et al.

Dan Cohen in an article published by Mint Press News described in detail how the system of Ukrainian strategic information works. Ukraine, with the help of foreign consultants and key media partners, built an effective network of PR-media agencies that actively churn out and promote fake news. In NATO countries whoever dares to question the correctness of this information is accused of being a “Putin’s agent”, attacked and excluded from public debate. The information space is so heavily guarded that it resembles an echo-chamber.

Ukrainian disinformation campaigns affect the judgment of both Western audiences and lawmakers. On March 8 when Ukrainian President Zelensky addressed the British House of Commons remotely, many members of parliament had no earphones to listen to the simultaneous translation of his speech. It didn’t matter. They liked the show and applauded enthusiastically. In their boxed-minds Zelensky had already been framed as “our good guy in Kiev”, and any script, even an incomprehensible one, would do. On March 1 diplomats from Western countries and their allies walked out during a video link address by Russia’s Foreign Minister Lavrov at the UN Conference on Disarmament in Geneva. Boxed-brains are cognitively incapable to engage in discussions with those who hold different views, making diplomacy impossible. That’s why in lieu of diplomatic skills we see theatrics and media stunts, empty suits who deliver script lines and project moral superiority.

The West has found refuge in this media-generated make-believe world because it can no longer solve its systemic problems: instead of development and progress we see economic, social, intellectual and political regression, anxiety, frustration, delusions of grandeur and irrationality. The West has become completely self-referential.

Dystopian ideological and social-engineering projects such as Trans-humanism and the Great Reset are the only solutions Western elites can offer to address the inevitable implosion of a system they contributed to wreck.

These “solutions” require the suppression of pluralism, the curtailing of freedom of information and expression, the widespread use of violence to intimidate critical thinkers, disinformation and emotional manipulation, in short, the destruction of the very foundations of modern democracy, public discourse, rational debate and informed participation in decision-making processes. The cherry on top is that it is cynically packaged and marketed as a “victory of democracy against authoritarianism.” To project democracy first they had to kill it and then replace it with its simulation.

But a global communication and information space that doesn’t respect the principle of pluralism and mutual respect inevitably produces its own gravediggers. We already see how this global space is fragmenting into heavily defended information spaces along the lines of geopolitical spheres of influence. The U.S.-led globalization project is unravelling and that’s mainly due to its overambition.

The U.S. might be winning the information war in the West but any victory in the parallel universe created by the media could easily turn into a Pyrrhic one when reality reasserts itself.

Recent history tells us that carefully crafted narratives, disinformation and demonization of the opponent radicalize and polarize public opinion, but victory in the information battlefield doesn’t necessarily translate into military or political victory, as we have seen in Syria and Afghanistan.

While the collective West revels in its success after the nuclear option of banning all Russian media from the global infosphere it controls, it’s too blinded by hubris to even notice the inevitable fallout. Total control over the narrative is achieved through authoritarian measures and the repression of dissenting voices, that is a reversal of those inclusive democracy and universalist values that the West hypocritically claims to defend and is actively projecting in the Global South. In the ideological confrontation with countries it defines “authoritarian” the West is losing the edge it claimed to possess.

The unipolar, U.S.-led world order is coming to an end and the West is fast losing its influence. Russia is paying attention and in the future it might invest more energy in reaching non-Western audiences instead, that is people who aren’t as indoctrinated and impervious to truth, facts and reason as their Western counterparts.

While at the beginning of the information revolution China took measures to protect its digital sovereignty, for many reasons it took Russia longer to recognize the danger posed by a communication and information system that despite initial claims of being an open, level playing field, was actually rigged in favour of those who controlled it.

Russia’s initiative in Ukraine is not only a response to attacks on the population of Donbass and a way to forestall Ukraine’s accession to NATO. Its avowed goal to denazify Ukraine is a defensive response to the intense cognitive war operations that the U.S. has been conducting both inside Russia and in neighbouring countries. NATO’s eastward expansion wasn’t simply a military expansion, it led to the occupation of the psycho-cultural, information and political space as well.

After losing a strategic battle in the cognitive war, watching the normalization of Neo-Nazi Russophobia and realizing that hostile forces, both domestic and foreign, have become entrenched in Ukraine, Russia feels all the more obliged to win the war, as Andrei Ilnitsky explained in an interview to Zvezda. Ilnitsky recognized that “The main danger of cognitive warfare is that its consequences are irreversible and can manifest themselves through generations. People who speak the same language as us, suddenly became our enemies.” The erection of monuments to Stepan Bandera while those of Soviet soldiers were being destroyed, was not only an intolerable provocation for Russia – a country that lost 26.6 million people fighting Nazism in WW2 – it was also a tangible expression of the kind of erasure and rewriting of history that is not limited to Ukraine.

The current conflict in Ukraine shows that restoring a sense of reality exacts a heavy and bloody toll. Unfortunately in matters of national security painful decisions cannot be postponed indefinitely.