EU officials know pretty well what is coming, but the machine is paralysed by political elites still squashed by a post-war mentality.

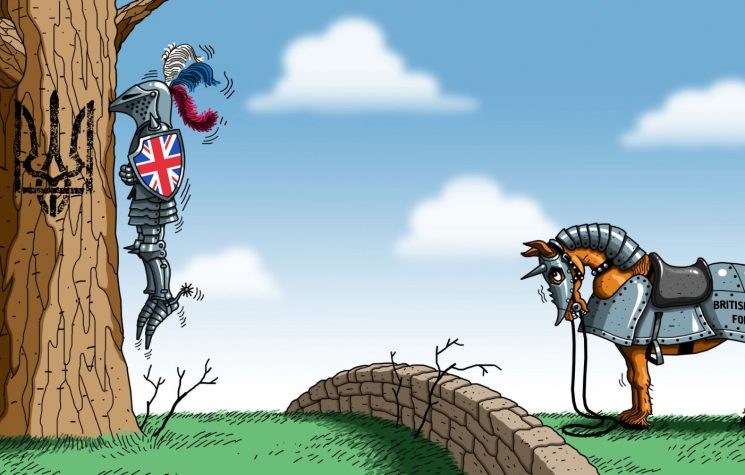

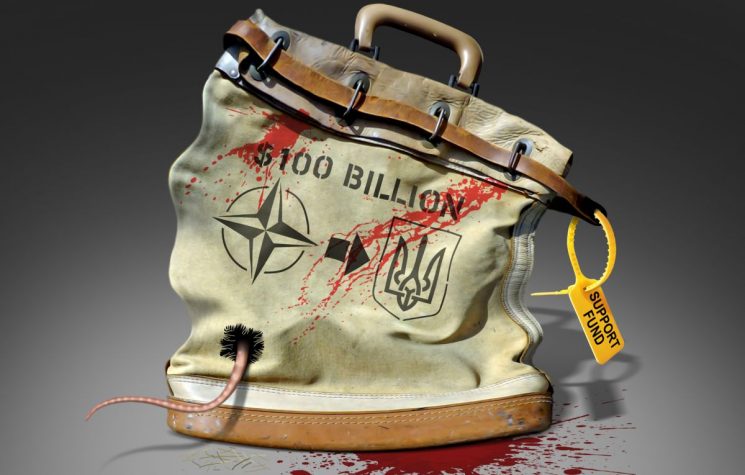

So far, the “war in Crimea” has been a paper war, fought in the media editorial offices, and let’s hope it stays that way forever. Anyway, also in this kind of Metaverse conflict, there is a clear loser: Europe. No one noticed the EU foreign policy chief Joseph Borrell weakly protesting that “Europeans have to be part of the table” in the Ukrainian talks. The general perception is that he doesn’t exist. Crushed by its bully American ally, faint-hearted and blind to its genuine interest, the Union is in a decline’s spiral. Less and less, it is an economic giant and more and more a political and military worm. In a tightly interconnected world, it has to restrain its crucial commercial relationship with China and Russia (and Iran) to please Washington.

Once comparable in principle with the American one, the European economy is falling back. From rough parity in 2008, the U.S.’s economy is now one-third bigger than the EU and the UK combined.

In 2008 the EU’s economy slightly exceeded America’s: $16.2 trillion against $14.7 trillion. By 2020, the U.S. economy had grown to $20.9 trillion, whereas the EU’s had fallen to $15.7 trillion. The former major general in the People’s Liberation Army Air Force Qiao Liang’s studies brilliantly pointed out that Washington is ruling through a weaponised dollar. The world’s primary reserve currency accounts for about 60% of official foreign exchange reserves, while the euro for only 21%. Sadly smiling, one could remember the 2000’s Saddam’s switch from the dollar to the euro for oil trading. It was an attempt to rebuke Washington’s hard-line on sanctions and encourage Europeans to challenge it. We know how it ended.

Europe is almost irrevocably falling behind China and the U.S. in the global race to technological leadership. Inside the EU, everyone is worried about the over-dependence on foreign-owned technology providers and the lack of industrial edge as in the semiconductors field. These concerns are particularly acute in the realms where “Europe does not have a strong indigenous industrial base, such as in cloud computing (76 per cent express concerns), artificial intelligence (68 per cent), and to a lesser extent by 5G mobile technology (54 per cent)”.

Have you ever seen a working European PC operative system? Or a competitive European search engine? But today’s problems are mainly EDTs, the Emerging and Disruptive Technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), autonomous weapons systems, big data, biotechnologies and quantum technologies. They are strategic and can give adversaries significant advantages, overtake existing governance systems, outpace regulatory efforts, and subvert military concepts and dual-use capabilities.

Europe is lagging behind also in the military field. European ground forces are mainly tailored for peacekeeping or anti-terrorist mission. Accustomed to occasionally fighting against a technologically inferior enemy, they are entirely unprepared against a real powerful army. Their command and communication infrastructure are highly vulnerable to the most advanced electronic warfare.

Still, it would be a gross attitude to insinuate that they are all a bunch of incompetent in Brussels. They know pretty well what is coming, but the machine is paralysed by political elites still squashed by a post-war mentality. Then, sometimes, the Americans forget to keep up the appearances; recently, Biden threatened to close for retaliation North Stream II, a pipeline on a foreign country over which Washington haven’t any jurisdiction. You can write unpalatable university papers full of data, but to say it in one world: Europe is an American colony.

Sometimes someone tries to break the chain with little success. In a famous speech at the Sorbonne in 2017, French President Emmanuel Macron said: “Only Europe can, in a word, guarantee genuine sovereignty or ability to exist in today’s world to defend values and interests”.

It was the first time that a European leader stressed the need for the EU’s strategic autonomy comprehensively, and the word “sovereignty” sounded like a bomb. The reaction of the other states of the Union was freezing cold. Many suspected a covert attempt to enhance the French military industries behind the grand idea. Even though it might also be partially true, the main issue was the usual lack of political perspectives and the petty particularism that still hold way in the relationship among the European partners.

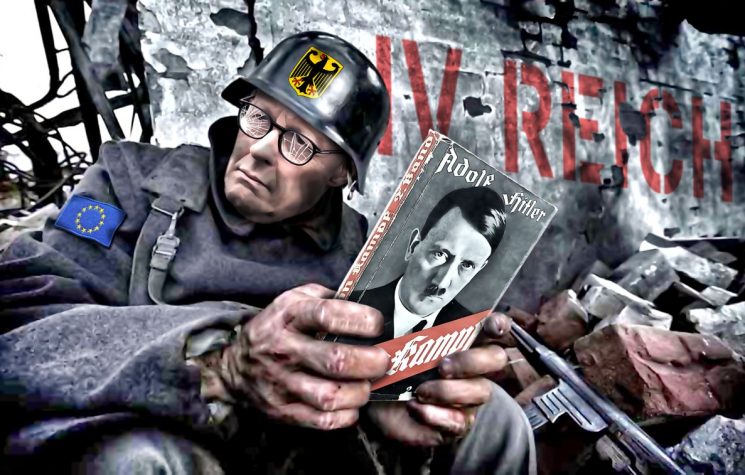

This narrow-minded stance is deeply rooted in recent history. The substantial European enlargement of 2004, when ten nations, the great majority from the former Communist bloc, joined the EU in one fell swoop, was substantially a rushed way to attract the countries in the NATO’S foyer. Especially at the time, it was an appealing idea. Still, the absorption process, dense with bureaucratic steps, lacks accurate political compatibility assessments or a realistic reflection on a practicable roadmap. The result was an almost paralysed giant, in which some countries like Poland or Baltic countries trusted more Washington than Brussels despite being inside the Union. Their fear of the Soviet Empire has understandable links to their history, but they don’t like to realise that USSR and its socialist mission is over forever. They are stuck in the past and see Germany’s efforts to protect its legitimate business with Moscow as a betrayal.

Macron’s bold push for European sovereignty clashes with a fragmented reality. What is Europe? Brussels’ ruthless neoliberalism? Berlin’s Rhine capitalism, Budapest’s illiberal democracy? Warsaw’s Catholic ethical state? Up to now, only His American Master’s Voice brings everyone together, unfortunately not according to the true Union’s interests.

In a much-quoted article, written for the Financial Times and then rejected for unclear reasons, Professor Sergey Karaganov, a man said to be near the Kremlin, talks of a “wider Greater Asian framework”. Inside it, “Russia needs a safe and friendly Western flank in the future world competition. Europe without Russia or even against it has been rapidly losing its international positions”.

A besieged Russia may be tuning into Beijing wavelength for self-preservation, but its natural destiny is a bridge with the West. A Europe conscious of its strength must recognise that a good economic relationship with Russia is a geopolitical truism. At the same time, you cannot forget the American elephant in the room. It is unthinkable for a strong “sovereign” Union to cut its ties with WWII’s “Liberators” (even though the USSR paid the highest price to beat the Nazis). But the European can try to contain the over-power of the dollar a little more successfully. The problem with the American is remaining friends without being suffocated from the excesses of such a big guy’s friendship.