Diana Johnstone assesses the recent German election, the decline of the traditional left, and its implications for relations with the U.S. and Russia.

By Diana JOHNSTONE

There was no clear winner in Germany’s Sept. 26 elections. No party has a strong majority, no strong leader is in sight. Weak national leadership has become the model for liberal Western democracy. And weak leadership is unlikely to resist powerful established interests.

To put it more clearly, the forthcoming German government, to be formed by a coalition of parties, is not very likely to rebel against the influence of the pro-U.S. Atlanticist institutions that have directed the policy of the German Federal Republic since it was founded in 1949 under Washington’s auspices. The United States exercises direct and daily influence on German policy-makers in NATO, German media, civil society organizations and personal relationships built up through contacts of all kinds.

Only two of the five parties in the new Bundestag are at all critical of NATO, and they are on the polar margins: the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) on the right and Die Linke (The Left) on the left, outside whichever government emerges. They are the only ones in favor of normalized relations with Russia. Both have at times appealed to neglected East Germans but there is animosity between them.

Which Coalition?

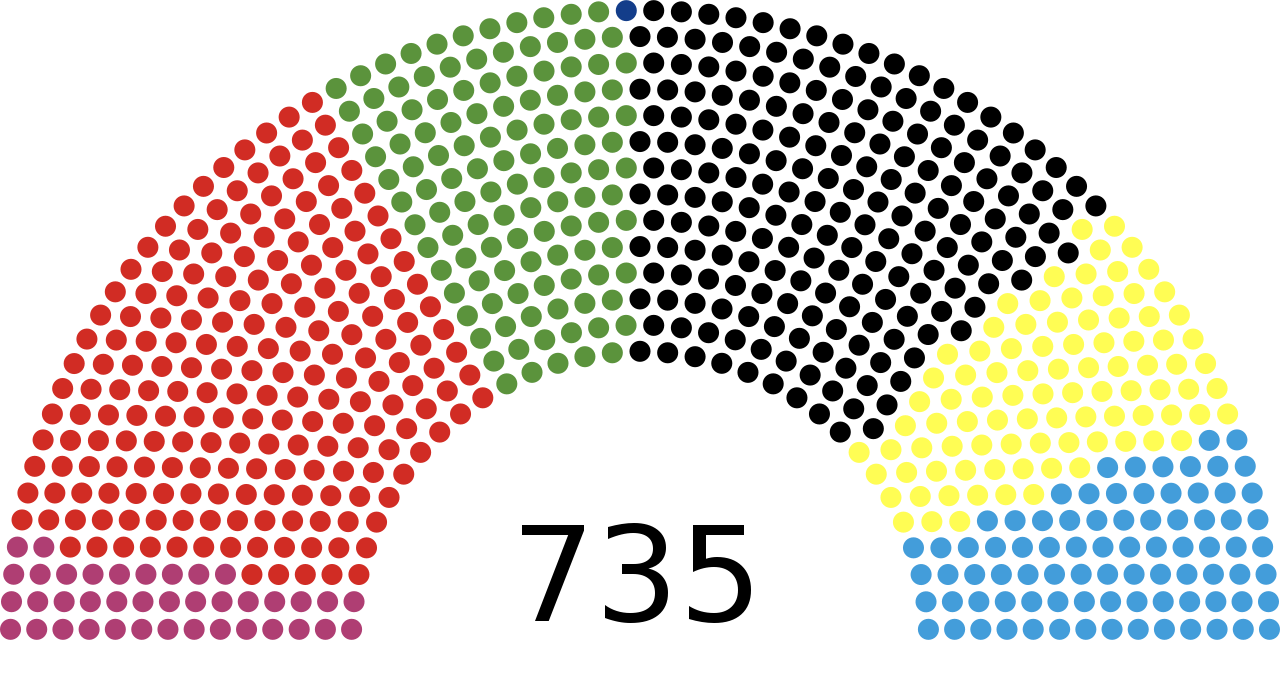

Bundestag composition after 2021 election. (Furfur/Wikimedia Commons)

The easiest and probably most stable coalition would be between the two parties that scored highest, the established center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the center-right Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU). Between the two of them, they won a majority of votes: the SPD with 25.7 percent of the vote and 208 of the 735 seats in the Bundestag. The CDU came in second with 24.1 percent of the vote and 196 seats. An SPD-CDU coalition would be in continuity with the outgoing government headed by Chancellor Angela Merkel, but neither party likes the prospect.

The election marked an unexpected comeback for the SPD, clearly not out of any burst of enthusiasm but from rejection of the others. The CDU lead candidate Armin Laschet ran a pitifully weak campaign, leading his party to an historic low. During the campaign, a video from 2016, at a time when many East Germans were opposing Merkel’s mass immigration policy, showed Laschet displaying total contempt for his East German compatriots by claiming that the German Democratic Republic (socialist East Germany) “permanently destroyed not only the country but also the minds of the people. …whole swaths of the country have not learned that you have respect for other people.”

This contributed to collapsing support for the CDU in the East.

The leading SPD candidate, Olaf Scholz, was not very exciting either. But he looked good compared to Laschet, so voters unexpectedly fell back to voting for the SPD. Logically, Scholz should head the new government. But the SPD has early on spoken out against a renewal of the “Big Coalition” between SPD and CDU (the GroKo) and the CDU would not like to be in second place.

So the odds are on a “traffic light” coalition between the SPD (red), the Greens and the FDP (liberals, gold or yellow) who got 11.5 percent and 92 seats.

Stop and Go Coalition

Annalena Baerbock (Wikimedia Commons)

Last April, the German Greens were dreaming that they would come in first, as opinion polls then suggested, and their young, inexperienced candidate, Annalena Baerbock, would succeed Angela Merkel as Chancellor. In those days, she was sycophantishly interviewed for the Atlantic Council by Fareed Zakaria. For a German who had studied in both the U.S. and the U.K., her English was surprisingly awkward, but as she praised eternal U.S.-German collaboration, she helped it along by echoing a trite phrase or two from Joe Biden.

Biden 2019: “The United States urgently needs to embrace greater ambition on an epic scale to meet the scope of this challenge.”

Baerbock 2021: “We urgently need to embrace greater ambition on an epic scale to meet the scope of the problems.”

However, as the campaign proceeded, Baerbock’s utter mediocrity became more and more blatant, enforced by revelations that she had hyped her CV, failed to declare party payments and heavily plagiarized equally boring sources for her book, optimistically titled Now: How we renew our country.

Finally, the Greens fell into third place, with 14.8 percent of the vote and 118 seats. That is not enough to form a coalition majority with either of the two big centrist parties, so if the SPD and CDU don’t get together, the FDP must be part of the equation along with the Greens. This promises domestic policy quarrels from the start, as the FDP wants an austere budget with low taxes and the Greens want the opposite. The FDP is after all, fundamentally a free market business party whereas the Greens want to raise taxes on higher incomes. And their differences do not stop there.

Together Against Russia

Merkel and Putin in Moscow, January 2020. (Russian President/Wikimedia Commons)

But there is one area on which these two runner-up parties can agree: hostility toward Russia. The Merkel government, with its belligerent woman defense minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, has already been an enthusiastic participant in NATO military war game gestures of hostility toward Russia, and a “traffic light” coalition threatens to be even worse.

The leading Green candidate has gone farthest in Russia-bashing, even demanding that Germany refuse to purchase natural gas from Russia via the now-completed Nord Stream 2 pipeline. Considering the growing threat of energy shortages resulting from Germany’s simultaneous rejection of nuclear power (basically out of fear of a Fukushima-type accident) and planned rapid phase-out of coal (for reasons of CO2 emissions), rejection of Russian natural gas is a luxury Germany simply can’t afford. Especially since Germany’s large park of windmills have since last year failed to produce the renewable energy expected when the wind refused to blow.

One might think that the pressing need for Russian gas would incite German business interests to impose a normalization of German-Russian relations. But this does not seem to be happening.

U.S.-led sanctions have decreased Russian-German trade in recent years. And somehow, there is a trend in German ruling circles to forgo normal commercial relations with Russia in favor of extending decisive German influence over countries between Germany and Russia, notably the large, mismanaged, potential economic prize that is Ukraine.

Anglo Attitude in Germany

Under U.S. tutelage for decades, much of the present German ruling class seems to have interiorized the peculiar American imperial attitude, an arrogant power projection draped in political self-righteousness. This characteristic Anglo-American attitude, forged in the British Empire, is currently to be found in Germany and northern Europe, and will find expression in the virtual “Summit for Democracy” which President Biden is convening in December. This is intended to solidify a new ideological Cold War between the Good, led by the United States, and the Evil—those who are not allowed in the club.

Joschka Fischer (Wikimedia Commons)

The community of Democracies will proclaim themselves champions of combating authoritarianism, fighting corruption, and promoting respect for human rights. The countries opposed by these paragons of virtue will be condemned for their sins and can be considered fair game for sanctions, subversion and whatever other cybernetic or military means may induce them to repent and take the path of Western virtue.

Nobody is more permeated with this self-righteousness than the Green Party of Germany. This makes it the perfect partner in a German government that wants to overcome its repentance for World War II and wage a “Good War” – as it did bombing Yugoslavia in 1999 with Green Joschka Fischer as foreign minister.

The Story Tellers

After over 75 years of military and political occupation by the United States, Germany and Japan are obvious candidates for a Washington-led reconstitution of the Axis Powers, opposing Russia and China as in the past, but proclaiming an ideology of anti-fascism, anti-authoritarianism, human rights, not to mention gender variety and equality.

The fascists felt good about themselves in their day, and the anti-authoritarians can feel good about themselves in theirs. They are helped along by the storytellers not only in the mainstream media but also, for policy-makers in Western governments, by the foundations, the think tanks, financed by a “civil society” that includes big investors in the weapons industry.

A recent strategy paper published by the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) outlines a more aggressive German foreign policy. Faced with alleged Russian propaganda and “targeted disinformation” by Russia intended to “damage NATO’s reputation,” the paper calls for creation of a “non-governmental rating agency” to evaluate media. By a funny coincidence, YouTube just expelled the Russian German-language news channel RT-de (which can still be viewed on Internet).

But the DGAP also calls for more determined “action against enemies of democracy in Germany and the EU.” Better still, it demands stronger German interference in Russia’s internal affairs to promote change.

Think tank analysis bases its alarm over “the Russian threat” on a far-fetched analysis of the Ukrainian crisis of 2014. To anyone with any knowledge of the historic background and a bit of common sense, Russia’s moves in response to the U.S.-backed coup in Kiev are perfectly clear and rational.

The U.S. installed an anti-Russian puppet government declaring its desire to join NATO. This was an immediate threat to Russia’s principal long-standing naval base in Crimea, so long as Crimea was part of Ukraine. But since the population of Crimea was largely Russian and had never wanted to be part of Ukraine (it was transferred from Russia to Ukraine in 1954 without consulting the population when both were part of the Soviet Union), the easy solution for Russia was to sponsor a referendum in which Crimeans predictably voted to return to Russia.

This peaceful return was then willfully interpreted as a signal that Russia was preparing to invade and conquer its neighbors. The Baltic States, Poland and even German leaders all feign alarm at this preposterous interpretation.

However, even the Greens, who excel in verbal Russia-bashing, do not want Germany to spend the 2 percent of economic output on “defense” as demanded by Washington. When the Germans call for a special EU defense force, they are in an ambiguous position. They do not want the same such force as advocated by the French, whose superior arms, including nuclear weapons, would be dominant. Rather, for the Germans any such force must be closely tied to NATO. In fact, nobody seriously imagines the EU defending itself against Russia, and a more or less independent EU force would surely be earmarked for interventions in the global South or the Balkans, in cahoots with the U.S. and NATO.

The Vanishing Left

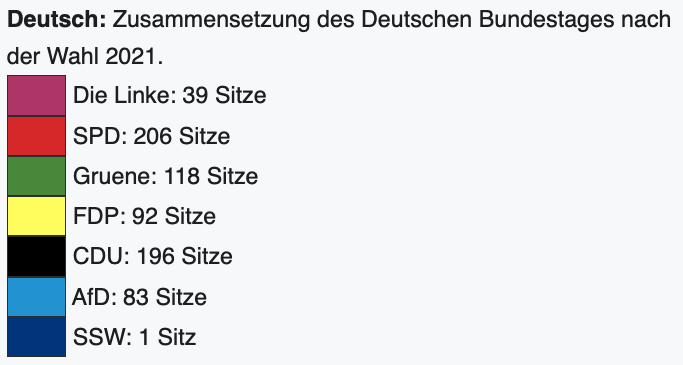

Sahra Wagenknecht addresses media. (Die Linke/Flickr)

Of the two marginalized opposition parties, the AfD maintained its strength in two East German states, Saxony and Thüringen, winning 10.3 percent of the vote and 83 seats. As for the Left party, Die Linke , with 4.9 percent of the vote it failed to go over the 5 percent hurdle for Bundestag membership, but got 39 members anyway due to a provision in Germany’s complex voting system which lets a party in if three of its candidates come in first in their conscription. Die Linke did so in Berllin and Leipzig and thus has 39 members in the parliament, including its most popular member, Sahra Wagenknecht, whom much of the party had been attacking throughout the campaign.

Wagenknecht led up to the election by publishing a book entitled Die Selbstgerechten (the Self-Righteous) in which she attacked the contemporary identity politics, woke left and called for a return to traditional left defense of the working class and anti-war policies. The exemplary self-righteous are the Greens, but their example had been adopted so thoroughly by Left party leaders that they felt targeted by Wagenknecht and struck back.

The election was a foreseeable disaster for Die Linke, and Wagenknecht had foreseen it clearly. During the campaign, Linke leaders were enchanted by the imaginary prospect of getting into the government as junior partner in a “red-green-red” coalition between the SPD, the Greens and themselves. To facilitate this unlikely outcome, they spent their time expressing their willingness to set aside their principles out of a realism that was anything but realistic.

The mainstream parties demanded that any party entering the government must be in favor of NATO. Die Linke is formally for its abolition, but leaders made clear they would forget about that.

As a pale copy of the Greens, they lost most of their voters. Notably, the Left party got fewer working class votes than any other party.

In its compromise mood, Die Linke in its campaign did not play up its role as the principal anti-war party in Germany. It failed to pound away at exposing anti-Russian propaganda designed to win public support for the NATO military buildup surrounding Russia.

Only the AfD pointedly asked the German government to clarify details of the preposterous Alexei Navalny tall tale sold to the public to arouse self-righteous indignation against Russia. In a parliamentary question, the AfD asked the government whether, as reported, Bellingcat financed Navalny’s expensive stay in the Black Forest where he made a dishonest propaganda film attacking Vladimir Putin. With some delay, the German government claimed to neither know nor care enough to investigate.

The Navalny story is crammed with improbabilities, blatant contradictions and strong indications of being the creation of British intelligence. A left party concerned with preserving peaceful relations should have been leading the challenge to get to the truth. It should have been speaking out against German participation in plans to send military forces to the Pacific to annoy China. But instead, Left leaders yearned to be accepted among the self-righteous.

The next German government will be self-righteous without them.