To the less favoured races, European justice has few benefits to offer, Stephen Karganovic writes.

Enlightened Europe has been vigorously displaying its fabled values lately.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) just recently responded in the complaint brought by the Russian Federation against Ukraine for the mistreatment of the latter’s citizens based on their ethnic, religious, cultural, and linguistic self-identification. To quote more directly the topics covered in the complaint: “The case concerns the Russian Government’s allegation of an administrative practice in Ukraine of, among other things, killings, abductions, forced displacement, interference with the right to vote, restrictions on the use of the Russian language and attacks on Russian embassies and consulates. They also complain about the water supply to Crimea at the Northern Crimean Canal being switched off and allege that Ukraine was responsible for the deaths of those on board Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 because it failed to close its airspace.”

By any measure, these are serious complaints. Such violations, if true, go to the very core of the European and, more broadly, Western system of values. By those enlightened standards, there is no misconduct much worse than “killings, abductions, forced displacement, interference with the right to vote, restrictions on the use of … language.” Countries are put under sanctions and threatened with the use of force under the “right to protect” doctrine contrived for the benefit of victim populations for far less than that. (Cases in point: Belarus, Syria, Cuba, Venezuela, and the list could go on.) The Russian Federation, while alleging cited misbehaviour, neither imposed sanctions on the Ukraine nor threatened to march in and restore some semblance of legal order and security by unilateral, self-righteous intervention. Instead, it is seeking a judicial review of the facts and asking for a legal ruling of the European Court of Human Rights, a seemingly restrained and reasonable course of action. Pending a full consideration of the evidence in the case, it asked for an interim ruling, or what is called a restraining order in America, to caution the Ukrainian authorities from tolerating the cited misconduct should it in the meantime become aware of it. A more sensible request under the circumstances is difficult to imagine.

That is why under the circumstances ECHR’s response to the request for an interim ruling is puzzling, to put it mildly:

“The Court decided to reject the request under Rule 39 of the Rules of Court since it did not involve a serious risk of irreparable harm of a core right under the European Convention on Human Rights.”

Are we to understand that in a stable, law-based political system such as the Ukraine, no ideological extremists endangering the peace and security of citizens have been detected, and that the occurrence of killings, abductions, forced displacement, interference with the right to vote and other infractions of the European Convention, such as the burning alive of several dozen people in Odessa a few years ago, are but wild and unsubstantiated rumours, to which no extraordinary attention should be paid and thus no urgent ameliorative action is required? It would appear so, and also that, according to the preliminary judgment of ECHR, in the Ukraine all core rights are prima facie safe and secure, and mercifully are under no threat of “irreparable harm.”

But in its July 13, 2021, ruling entitled “Russia failed to justify the lack of any opportunity for same-sex couples to have their relationship formally acknowledged,” the same European court sent an eloquent virtue signal of its actual vision of “core values”. In a ruling obligating Russia to disregard its legislation and to defer instead to the demands of the LGBT agenda, and by vivid contrast to its stance on paltry matters such as “killings, abductions, forced displacement, interference with the right to vote” and the like, ECHR ordered Russia to institutionalise same-sex marriages. It thus indicated clearly which are the issues that do trigger an immediate and energetic response of human rights watchdogs in the civilised countries.

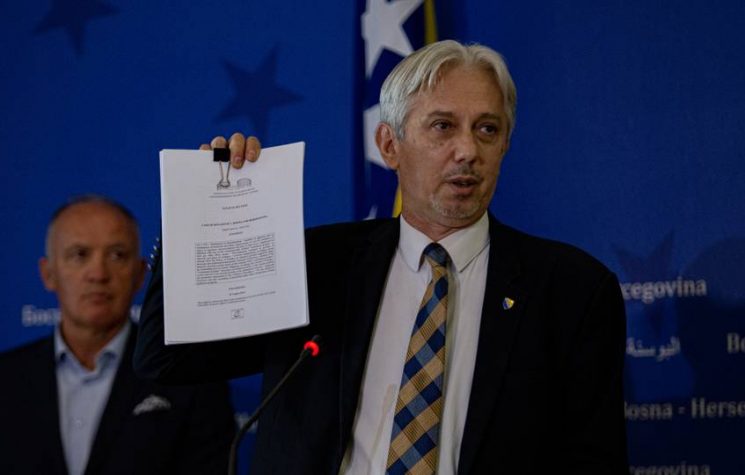

To put these matters in a broader perspective, mention should be made of Mrs. Dragica Gašić and her ghastly predicament in the town of Djakovica, located in the Serbian province of Kosovo and Metohija, occupied by NATO since 1999 as a showcase of what R2P interventions can do in furtherance of the “core values” to which the European Court of Human Rights is presumably committed.

Serbian Kosovo returnee, Dragica Gašić

NATO, it should be recalled, is supposed to be the muscle behind those superior values, while ECHR’s task is to maintain the moral high ground by taking upon itself their theoretical articulation. Mrs. Gašić was one of several hundred thousand ethnically cleansed residents of Kosovo who, in 1999, judged it prudent to flee before NATO’s “liberation forces” and the local armed gangs allied with them, and to take temporary refuge in the remaining unoccupied, you might say Vichy, Serbia. After repeated assurances of “normalisation” in Kosovo (an expression rich in ironic undertones within the context of 1950s and 1960s East European history), Mrs. Gašić succumbed to the temptation of taking the Pied Pipers up on their promises. Several months ago, she decided to move back to her abandoned home in Djakovica in order to continue the life that was brusquely interrupted by the humanitarian intervention of two decades ago.

Arguably, that may have been one of the worst decisions she ever made. Although she now is the only person of her ethnicity living in the town to which she has returned, her presence apparently is an intolerable irritant to the community of her neighbours, who are rather openly favoured by NATO, NATO-friendly local authorities, as well as the majority of European chancelleries. Although this lone woman poses no visible political or security threat to anyone, she has been intimidated and in no uncertain terms made to feel unwanted and socially unintegrated (in strikingly similar fashion to the ultimately successful Russian same-sex applicants to ECHR, but with the distinction that in her case there is not the slightest recognition of her plight from any quarter). Her modest application recently to the authorities to allow her to install a steel door in her apartment for personal protection was denied since, apparently inspired by the legal teaching of the European Court of Human Rights in the Ukrainian case, they failed to see any “serious risk of irreparable harm of a core right”. On July 29, in her absence the apartment was burglarised, her personal belongings were ransacked and partially carried away, including the mourning outfit for her deceased father and her diabetes medications.

Mrs. Gašić was not so lucky as to be made a subject of international litigation initiated by any government, not even her own. Nor is she even on the radar screen of any of the numerous international “core right” watchdogs and rapporteurs swarming in Kosovo. But that is scarcely surprising.

To the less favoured races, European justice has few benefits to offer.