Today, crisis is the hour in the region, writes Vijay Prashad, with an eye on Port-au-Prince and Havana.

By Vijay PRASHAD

In 1963, the Trinidadian writer CLR James released a second edition of his classic 1938 study of the Haitian Revolution, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution.

For the new edition, James wrote an appendix with the suggestive title “From Toussaint L’Ouverture to Fidel Castro.” In the opening page of the appendix, he located the twin revolutions of Haiti (1804) and Cuba (1959) in the context of the West Indian islands:

“The people who made them, the problems and the attempts to solve them, are peculiarly West Indian, the product of a peculiar origin and a peculiar history.”

Thrice James uses the word “peculiar,” which emerges from the Latin peculiaris for “private property” (pecu is the Latin word for “cattle,” the essence of ancient property).

Property is at the heart of the origin and history of the modern West Indies. By the end of the 17th century, the European conquistadors and colonialists had massacred the inhabitants of the West Indies. On St. Kitts in 1626, English and French colonialists massacred between 2,000 and 4,000 Caribs — including Chief Tegremond — in the Kalinago genocide, which Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre wrote about in 1654.

Having annihilated the island’s native people, the Europeans brought in African men and women who had been captured and enslaved. What unites the West Indian islands is not language and culture, but the wretchedness of slavery, rooted in an oppressive plantation economy. Both Haiti and Cuba are products of this “peculiarity,” the one being bold enough to break the shackles in 1804 and the other able to follow a century and a half later.

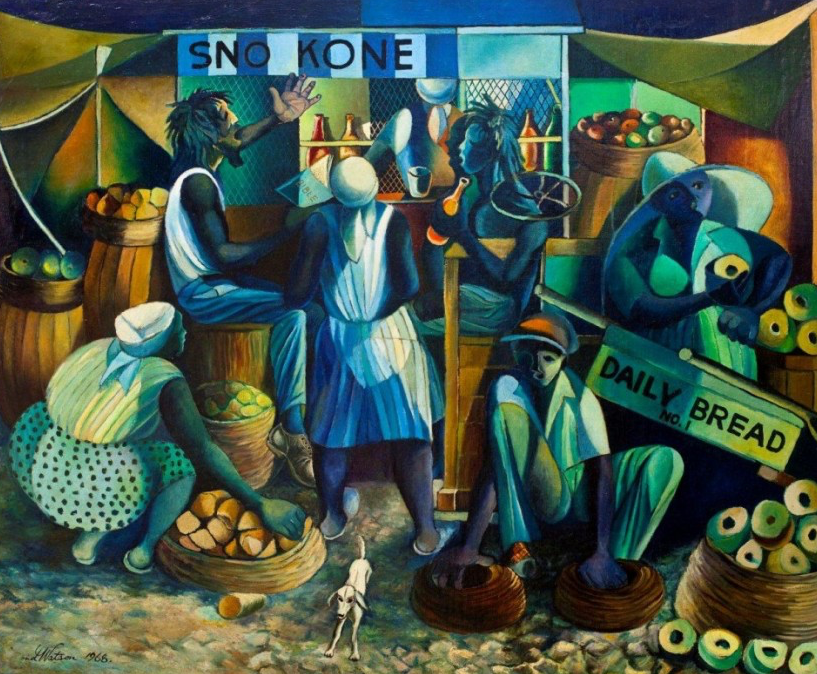

Osmond Watson, Jamaica, “City Life,” 1968.

Today, crisis is the hour in the Caribbean.

On July 7, just outside of Haiti’s capital of Port-au-Prince, gunmen broke into the home of President Jovenel Moïse, assassinated him in cold blood, and then fled. The country — already wracked by social upheaval sparked by the late president’s policies — has now plunged even deeper into crisis.

Already, Moïse had forcefully extended his presidential mandate beyond his term as the country struggled with the burdens of being dependent on international agencies, trapped by a century-long economic crisis and struck hard by the pandemic. Protests had become commonplace across Haiti as the prices of everything skyrocketed and as no effective government came to the aid of a population in despair.

But Moïse was not killed because of this proximate crisis. More mysterious forces are at work: U.S.-based Haitian religious leaders, narco-traffickers and Colombian mercenaries. This is a saga that is best written as a fictional thriller.

Four days after Moïse’s assassination, Cuba experienced a set of protests from people expressing their frustration with shortages of goods and a recent spike of Covid-19 infections. Within hours of receiving the news that the protests had emerged, Cuba’s President Miguel Díaz-Canel went to the streets of San Antonio de los Baños, south of Havana, to march with the protestors.

Díaz-Canel and his government reminded the 11 million Cubans that the country has suffered greatly from the six-decade-long illegal U.S. blockade, that it is in the grip of former U.S. President Donald Trump’s 243 additional “coercive measures” and that it will fight off the twin problems of Covid-19 and a debt crisis with its characteristic resolve.

Nonetheless, a malicious social media campaign attempted to use these protests as a sign that the government of Díaz-Canel and the Cuban Revolution should be overthrown.

It was clarified a few days later that this campaign was run from Miami. And from Washington, D.C., the drums of regime change sounded loudly. But they have not found find much of an echo in Cuba. Cuba has its own revolutionary rhythms.

Eduardo Abela, Cuba, “Los Guajiros,” 1938.

In 1804, the Haitian Revolution — a rebellion of the plantation proletariat who struck against the agricultural factories that produced sugar and profit — sent up a flare of freedom across the colonized world. A century and a half later, the Cubans fired their own flare.

The response to each of these revolutions from the fossilized magnates of Paris and Washington was the same: suffocate the stirrings of freedom by indemnities and blockades.

In 1825, the French demanded through force that the Haitians pay 150 million francs for the loss of property (namely human beings). Alone in the Caribbean, the Haitians felt that they had no choice but to pay up, which they did to France (until 1893) and then to the United States (until 1947). The total bill over the 122 years amounts to $21 billion. When Haiti’s President Jean-Bertrand Aristide tried to recover those billions from France in 2003, he was removed from office by a coup d’état.

After the United States occupied Cuba in 1898, it ran the island like a gangster’s playground. Any attempt by the Cubans to exercise their sovereignty was squashed with terrible force, including invasions by U.S. forces in 1906-1909, 1912, 1917-1922 and 1933.

The United States backed General Fulgencio Batista (1940-1944 and 1952-1959) despite all the evidence of his brutality. After all, Batista protected U.S. interests and U.S. firms owned two-thirds of the country’s sugar industry and almost its entire service sector.

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 stands against this wretched history — a history of slavery and imperial domination.

How did the U.S. react? By imposing an economic blockade on the country from Oct. 19, 1960, that lasts to this day and has targeted everything from access to medical supplies, food and financing to barring Cuban imports and coercing third-party countries to do the same. It is a vindictive attack against a people who — like the Haitians — are trying to exercise their sovereignty.

Cuba’s Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez reported that between April 2019 and December 2020, the government lost $9.1 billion due to the blockade ($436 million per month). “At current prices,” he said, “the accumulated damages in six decades amount to over $147.8 billion, and against the price of gold, it amounts to over $1.3 trillion.”

None of this information would be available without the presence of media outlets such as Peoples Dispatch, which celebrates its three-year anniversary this week. We send our warmest greetings to the team and hope that you will bookmark their page to visit it several times a day for world news rooted in people’s struggles.

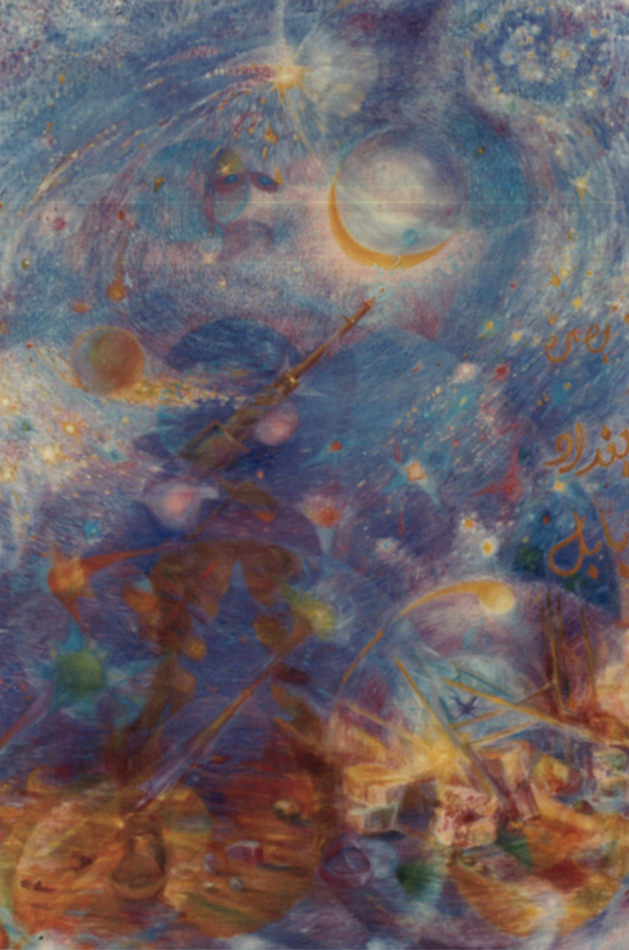

Bernadette Persaud, Guyana, “Gentlemen Under the Sky (Gulf War),” 1991.

On July 17, tens of thousands of Cubans took to the streets to defend their revolution and demand an end to the U.S. blockade. President Díaz-Canel said that the Cuba of “love, peace, unity, [and] solidarity” had asserted itself.

A few weeks before the most recent attack on Cuba and the assassination in Haiti, the United States armed forces conducted a major military exercise in Guyana called Tradewinds 2021 and another exercise in Panama called Panamax 2021.

Under the authority of the United States, a set of European militaries (France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom) — each with colonies in the region — joined Brazil and Canada to conduct Tradewinds with seven Caribbean countries (The Bahamas, Belize, Bermuda, Dominican Republic, Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago). In a show of force, the U.S. demanded that Iran cancel the movement of its ships to Venezuela in June ahead of the U.S.-sponsored military exercise.

The United States is eager to turn the Caribbean into its sea, subordinating the sovereignty of the islands. It was curious that Guyana’s Prime Minister Mark Phillips said that these U.S.-led war games strengthen the “Caribbean regional security system.” What they do, as our recent dossier on U.S. and French military bases in Africa shows, is to subordinate the Caribbean states to U.S. interests. The U.S. is using its increased military presence in Colombia and Guyana to increase pressure on Venezuela.

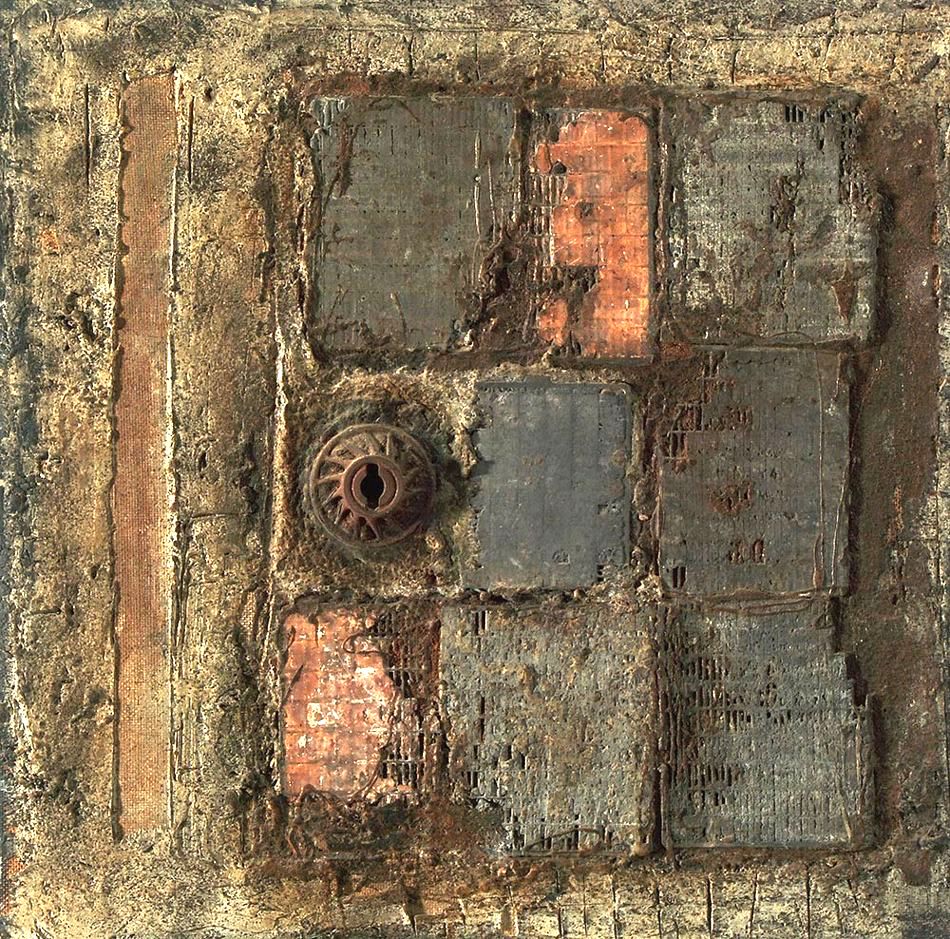

Elsa Gramcko, Venezuela, “El ojo de la cerradura” or “The Keyhole,” 1964.

Sovereign regionalism is not alien to the Caribbean, which has made four attempts to build a platform: the West Indian Federation (1958-1962), Caribbean Free Trade Association (1965-1973), Caribbean Community (1973-1989), and CARICOM (1989 to the present). What began as an anti-imperialist union has now devolved into a trade association that attempts to better integrate the region into world trade. The politics of the Caribbean are increasingly being drawn into orbit of the U.S. In 2010, the U.S. created the Caribbean Basic Security Initiative, whose agenda is shaped by Washington.

In 2011, our old friend Shridath Ramphal, Guyana’s foreign minister from 1972 to 1975, repeated the words of the great Grenadian radical T. A. Marryshow: “The West Indies must be West Indian’. In his article “Is the West Indies West Indian?,” he insisted that the conscious spelling of ‘The West Indies” with a capitalized “T” in “The” aims to signify the unity of the region. Without unity, the old imperialist pressures will prevail as they often do.

In 1975, the Cuban poet Nancy Morejón published a landmark poem called “Mujer Negra” or “Black Woman.” The poem opens with the terrible trade of human beings by the European colonialists, touches on the war of independence and then settles on the remarkable Cuban Revolution of 1959:

I came down from the Sierra

to put an end to capital and usurer,

to generals and to the bourgeoisie.

Now I exist: only today do we own, do we create.

Nothing is alien to us.

The land is ours.

Ours are the sea and sky,

the magic and vision.

My fellow people, here I see you dance

around the tree we are planting for communism.

Its prodigal wood already resounds.

The land is ours. Sovereignty is ours too. Our destiny is not to live as the subordinate beings of others. That is the message of Morejón and of the Cuban people who are building their sovereign lives, and it is the message of the Haitian people who want to advance their great Revolution of 1804.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research via consortiumnews.com