There is yet no reckoning for Australia’s SAS war crimes in Afghanistan, although details of horrendous atrocities are coming to light. A 2016 report detailing the extent of torture and extrajudicial killings by the Australian SAS forces in Afghanistan have been described as “fuelled by blood lust”, and compared on a scale to the infamous torture and murder practices at Abu Ghraib in Iraq.

The 2016 report which has recently been seen by two leading Australian news outlets, was compiled by sociologist Dr Samantha Crompvoets. Testimonies of war crimes, accompanied by the normalisation of such action and recurring impunity, have been characterised by a reliability in narration among different participants, pointing towards routine practices that escalated over time.

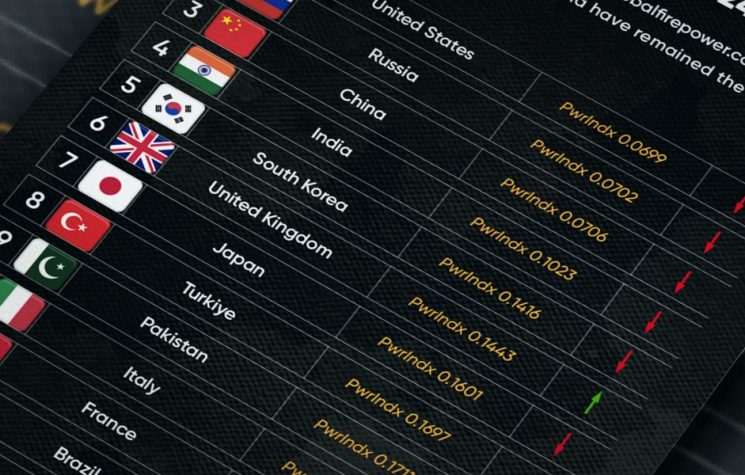

Notably, the report points towards an adulation of violence. The Australian special forces working alongside British and US counterparts held up the latter as the pinnacle of violence to emulate. However, the torture and killing of Afghan civilians by the Australian SAS is held on a par in terms of desensitisation and normalisation. A report earlier in March this year, which is based upon the witnessing of an execution of an Afghan man, states, “The visual image to me was, the guy had his hands up and then it was almost like target practice for that soldier.”

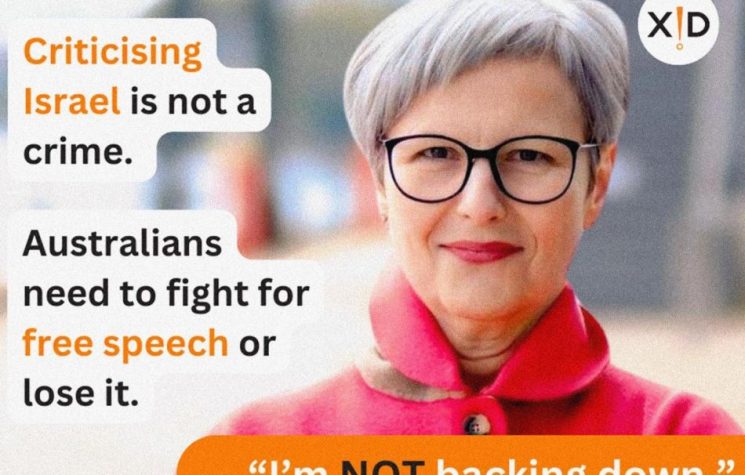

Human rights organisations in Australia and Afghanistan have called upon the Australian government to release the inquiry report into war crimes committed by the SAS, which commenced in 2016, in a manner which would hold the country accountable to upholding International Humanitarian Law. The open letter makes an important point that resonates even in relation to other countries subject to foreign intervention and impunity for the perpetrators. It states, “The Afghan people have remained trapped in an unbroken cycle of a 40 year long conflict which is profoundly rooted in a culture of impunity, with many actors operating in total disregard of local and international laws and norms in the firm belief that nobody will ever hold them accountable.”

Under the guise of foreign intervention and the democracy narrative which is used to sell war to the public, impunity for human rights violations is being cultivated. The lack of accountability is related to several processes, including policy, leadership failure, and dysfunctional communication between divisions; the latter amounting to secrecy that develops further possibilities for impunity.

One story featured in Australian media in March this year detailed the killing of an Afghan man who posed no threat to soldiers, and whose corpse was chewed upon by an assault dog. In another case captured on camera, another Afghan man, again posing no danger, is shot three times at point blank range – for no other reason than abuse of power, as indicated by the perpetrator.

Democracy and war crimes go hand in hand when it comes to foreign intervention and the bloody trail they leave behind. In an investigation by the Australian Defence Forces (ADF), the soldier who killed the Afghan man in a field was exonerated and is still serving in the Australian special forces; the narrative being that the victim had been seen with a radio, despite evidence to the contrary.

Such coverups are a regular occurrence which serve to perpetrate additional human rights violations. It is possible that the Australian government, as indicated by Defence Minister Linda Reynolds, will agree to publish parts of the report for “transparency” this month. The so-called War on Terror has unleashed a brand of state terror on targeted countries which so far has been met with an ingrained reticence from leaders to investigate accusations of war crimes. Between the bureaucratic delays of the International Criminal Court, and opposition to the institution by world leaders intent on saving the culture of impunity, there is little chance of implementing justice unless the international justice system is pressured to work against the globalisation of war.