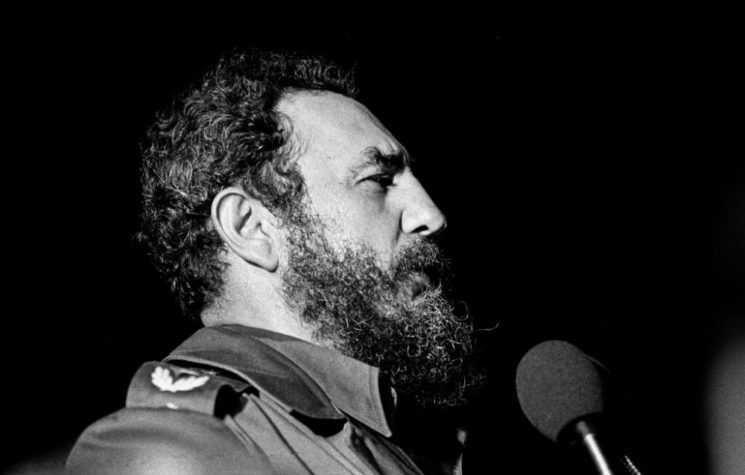

“When Batista’s coup took place in 1952, I’d already formulated a plan for the future. I decided to launch a revolutionary programme and organise a popular uprising. From that moment on, I had a clear idea of the struggle ahead and of the fundamental revolutionary ideas behind it, the ideas that are in History Will Absolve Me.”

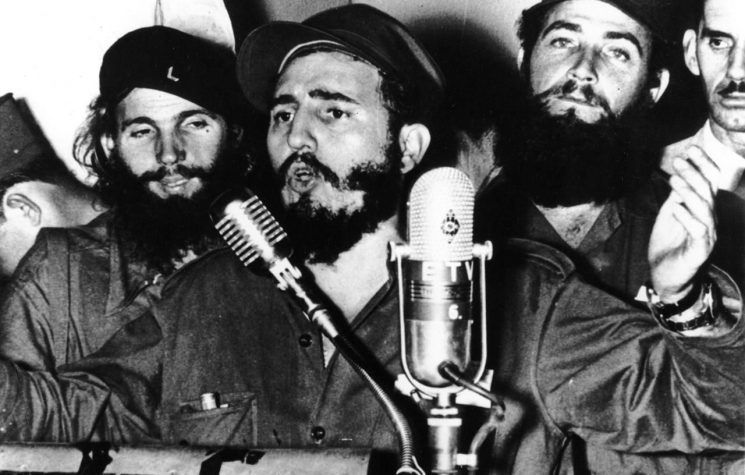

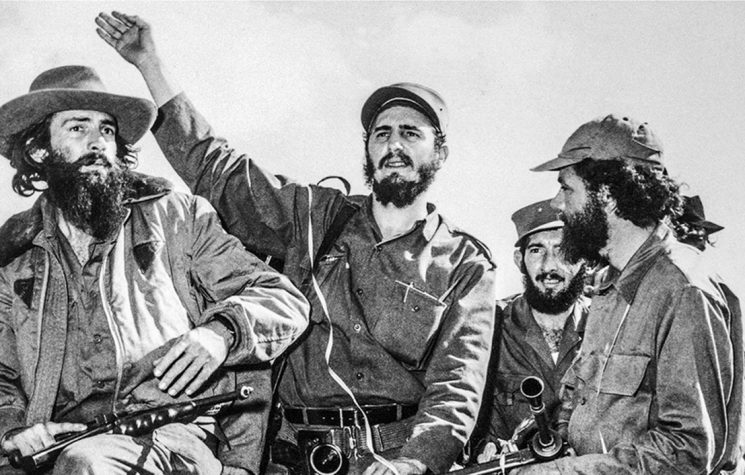

Just one year later, Fidel Castro would lead the attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba on July 26, 1953. It was a failed military attempt and 70 comrades taking part in the action were kidnapped, tortured and murdered, yet the action would mobilise Cubans against the tyranny of the right-wing, U.S.-backed dictator, Fulgencio Batista. Faced with a choice – to surrender or retreat to the mountains to continue planning the revolution – Fidel chose the latter. However, Batista’s patrols caught up with the revolutionary group. Fidel and his comrades were taken prisoners; Fidel’s life spared by the intervention of Lieutenant Pedro Sarria who warned the soldiers, “You can’t kill ideas.”

The importance of Moncada has been illustrated several times by Fidel in his commemorative speeches. In 1960, Fidel described Moncada thus: “And so, that 26 of July was just a minute for U.S., when the fight seemed to end, when the effort to be in the battle for the liberation of our people seemed to end, it was not the end, but the beginning.”

It is through Fidel’s prison letters written from the Isles of Pines, as well as through his defence speech, History Will Absolve Me, that the significance of Moncada and the revolutionary intent are placed at the helm. Of the crimes committed by Batista’s soldiers, Fidel wrote, “History has not seen a similar massacre, neither in the colony nor in the Republic.” The first revolutionary victim was Dr Mario Muñoz, who was killed by a shot to the head from the back, despite being unarmed and just carrying medical supplies in his bag, while also wearing medical attire. Abel Santamaría, one of the Moncada revolutionaries, was brutally tortured. His eyes were gouged out by Batista’s soldiers and presented to his sister, Haydee Santamaría, who was also arrested for participating in the attack. The brutality was not so much as deterrent as revenge by the Batista dictatorship, which ordered the killing of ten revolutionaries for every soldier.

In his defence speech, Fidel emphasised colonial liberation. Batista’s dictatorship thrived on terror; the Cuban Revolution planned for revolutionary education. The Moncada Barracks attack, therefore, in inscribed within the Cuban historical narrative as the launch of the Cuban Revolution. It is a collective revolutionary consciousness which continues to recognise the memory of Moncada as the first step in an ongoing revolutionary process, as Fidel meant it to be. For Fidel, the subsequent revolutionary triumph on January 1, 1959 also marked the beginning of a process in which an educated society would participate.

Similar sentiments were expressed by Cuban President Miguel Diaz Canel on this year’s commemoration of Moncada. July 26 is not just an annual commemoration but a reflection of revolutionary commitment. At present, and with U.S. hostility and diplomatic aggression against Cuba becoming more prominent, Moncada regenerates its significance in terms of the revolutionary process. The current Cuban commitment to internationalism as seen throughout the coronavirus pandemic may be far removed from Moncada in terms of action. Yet it is precisely what Fidel determined the revolution would be. The Cuban revolution created the space for education and internationalism to thrive. From changing Cuba to being an inspiration in Latin America and beyond, remembering the first visible revolutionary action by Fidel and his comrades must transcend the historical confines, in order to emulate the lasting vision determined prior to Moncada.