It is intriguing but almost inevitable that examination of so many European policies must begin with reference to the United States. The reason is that the US is majestically (and the word is used advisedly) important to Europe, and no matter what opinions may be held of Washington’s policies under the erratic Trump, these will always have influence in Europe’s capitals.

One major Europe-US consideration is the Trump administration’s decisions on nuclear strategy which have an enormous impact that will be likely to shape international relations indefinitely.

This has been examined by President Macron of France whose recent speech on Defence and Deterrence Strategy has not received the attention it merits in the US media. He delivered his talk at the military’s War College on February 7, and opened by making the point that he was the first president to speak there since Charles de Gaulle “announced on 3 November 1959, sixty years ago, the creation of what he then called the force de frappe”. The force de frappe is literally the nuclear ‘Strike Force’ (now less combatively referred to as ‘deterrence’) and is comparatively modest, consisting only of some 300 weapons, as assessed by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute in 2019.

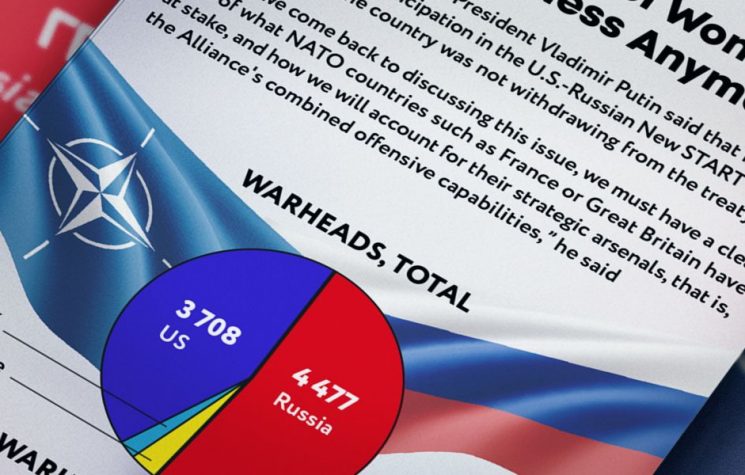

Of course the word ‘modest’ in reference to nuclear weapons’ arsenals is somewhat misleading, if only because 300 of them (or Israel’s 100 or so; China’s 290; Pakistan’s 200 or India’s 180) could destroy the world. But it is used in comparison to the arsenals of the nuclear super-powers, the US and Russia, which each have over 6,000. Macron said that “Russian-American bilateral treaties relate to a chapter of history – that of the Cold War – but also to a reality that is still relevant today, that of the considerable size of arsenals still being held by Moscow and Washington, without a possible comparison with those of other nuclear-weapon-States. In this respect, it is critical that the New Start Treaty be extended beyond 2021.” And there he put his finger on the button.

The New Start Treaty — the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty agreed between the US and Russia — was signed in 2010 and if Trump fails to take action it will expire in February 2021. Its main “Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms”, according to an April 2019 report by the US Congressional Research Service “limits each side to no more than 800 deployed and nondeployed land-based intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) launchers and deployed and nondeployed heavy bombers equipped to carry nuclear armaments… The treaty also limits each side to no more than 1,550 deployed warheads; those are the actual number of warheads on deployed ICBMs and SLBMs, and one warhead for each deployed heavy bomber.”

The accord could be described as modest but exceptionally important, and has been acknowledged as such by Russia whose deputy foreign minister, Sergey Ryabkov, stated on February 11 that the country has “confirmed its readiness at the highest level to extend this treaty without any preconditions and, moreover, to do it urgently.”

But in spite of the fact that Russian readiness “was officially brought to the notice of the American side by a diplomatic note at the end of last year” there has been no positive reaction from Washington, which is disturbing, to put it mildly. Macron was right in observing that “there can be no defence and security project of European citizens without political vision seeking to advance gradual rebuilding of confidence with Russia” and he has made it clear that for the moment there is little prospect of true détente (to use the old Cold War term) because the “divide between us is growing and dialogue is weakening precisely at a time when the number of security issues that need to be addressed with Moscow are increasing.”

But Trump does not appear to be prepared to talk with Russia about any security problems. As noted by Defense News on February 10, his fiscal 2021 budget details a massive increase in expenditure on nuclear weapons, which is not the signal that Washington should be sending to China and Russia. The $28.9 billion to be spent on nuclear modernisation includes over 4 billion for Columbia Class submarines, almost 3 billion on B-21 bombers, and a billion for the Trident missile life-extension programme. All of these are notably offensive “mutually assured destruction” style decisions, and by no stretch of the imagination can be described as confidence-building or indicative of desire to embrace the Start Treaty — which could be agreed by a simple presidential signature. There is no requirement for any legislative procedure.

The Washington Post, no champion of Russia, and indeed a fervent critic of Russian policies about almost everything, observed on February 10 in an editorial that “Putin wants to extend arms control. What’s Trump waiting for?” The paper referred to the New Start Treaty in supportive terms and notes that it “provides for intrusive verification and ensures stability in nuclear arsenals. If New Start lapses, both countries will be free to deploy more nuclear warheads and build new generations of weapons and delivery systems” — which has been heralded in the US by the Pentagon’s programmes.

At a meeting of the US-Nato military alliance in Brussels on February 12-13, however, there was no mention of Washington’s impending expansion of nuclear weapons’ capabilities, but much focus on criticising Russia and supporting Ukraine while attempting to justify Nato’s movement further away from Europe to “enhance Nato Mission Iraq” which is madness.

Macron has a wider and more pragmatic view of international affairs and wants Europe to devise “an international arms control agenda” because “the end of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, the uncertainties about the future of the New Start Treaty and the crisis of the conventional arms control regime in Europe have led to the possibility of a return of pure unhindered military and nuclear competition by 2021, which has not been seen since the end of the 1960s.”

Macron is concerned that dialogue is being rejected in favour of nuclear sabre-rattling, but unfortunately cannot rely for support from the only other nuclear weapons-capable country in Europe, the United Kingdom, which is squandering billions on its nuclear programme that its National Audit Office reported is facing “delays of between one and six years, with costs increasing by £1.3 bn.” In spite of this shambles the UK’s nuclear policy will not alter, because prime minister Johnson has approved expenditure on replacing the existing Trident nuclear missiles, and the independent Forces Network records that he voted for “a series of proposed spending cuts and changes to the welfare system in favour of spending on new nuclear weapons.”

Further, Britain is heavily influenced by Washington in its nuclear posture, as made clear by US Admiral Charles Richard whose testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee on February 13 included the statement that the new W-93 nuclear warhead will “support a parallel Replacement Warhead Program in the United Kingdom whose nuclear deterrent plays an absolutely vital role in Nato’s overall defence posture.”

It seems that in Europe Emmanuel Macron is a lonely voice in attempting to encourage Trump to renew the Arms Reduction Treaty and that his only significant supporter in moving towards dialogue with Russia is Angela Merkel, who has almost as many domestic political problems as he has. It is hoped that more nations will pay attention to Macron’s wise pronouncement that “there can be no defence and security project for European citizens without a political vision that seeks to progressively restore trust with Russia.”

If there is no movement towards dialogue with the intention of establishing a latter-day détente, and if Trump refuses to extend New Start, then the nuclear dominance option, as already being embraced by Washington, will further destabilise our already shaky world.