November 14 marks a year since a Chilean special unit known as the Comando Jungla fired 23 shots at Mapuche youth and activist Camilo Catrillanca while he was driving a tractor on his own land. Trained by the US and Colombia, the Comando Jungla are an anti-terror squad deployed to the Araucania region, in a move that fits with Chilean President Sebastian Piñera’s plans to militarise the area and prevent the Mapuche from mobilising against the ongoing dispossession of their land.

Last month, Chilean President Sebastian Piñera described the killing as “an abuse of power”. A year has passed since the murder and Catrillanca’s family are still seeking justice in Chilean courts. The latest impediment to justice is the appointment of the judge in charge of Catrillanca’s case, Francesco Boero Villagran, who represented the interests of the company Forestal Mininco in their legal proceedings against other Mapuche individuals. The company has encroached upon lands which are of cultural and spiritual significance to the Mapuche. Earlier this month, the government invoked the anti-terror laws against the Mapuche people in Temuco, for their sabotage actions of resistance against the company.

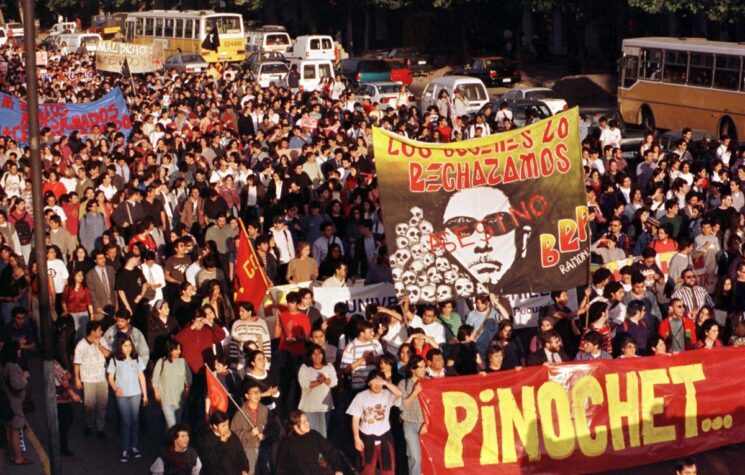

Chilean governments and their protection of social inequalities created the marginalisation of the Mapuche people from the rest of the population. However, the current protests calling for Piñera’s resignation and the drafting of a new constitution to replace Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorial legacy have shattered the prevailing illusion that the struggles of the Mapuche and the Chilean people are entirely separate issues.

Since the start of the protests last October, the Mapuche people have protested alongside Chileans, and the Mapuche flag has been prominent in the demonstrations. The military violence allowed by the Chilean government has targeted Chileans and Mapuches alike, with the extent of human rights violations committed becoming a reference to the crimes against humanity committed during the dictatorship era.

In light of the current developments, notably the unity between the Chilean people and the Mapuche, it is important to note the importance of the Mapuche struggle against neoliberal violence and exploitation. Their long history of resistance has, in fact, led to the toppling of colonial monuments in Chile which, until the protests, symbolised the glorification of earlier colonial conquest, while the historical crimes committed against the indigenous population were normalised under euphemisms such as “pacification” rather than genocide.

The reaffirmation of anti-colonial struggle against the erasure of Mapuche history, which remained unchallenged by Chilean governments in the democratic transition, is a departure point for this moment in Chilean politics where the people are calling for a new constitution. The unity exhibited by the Chilean people and the indigenous communities in Chile must be respected by recognising Chile as a plurinational state. It must be remembered that the colonialism that ravaged Chile was the start of a process that culminated in the neoliberal experiment enforced by Pinochet upon Chileans and which the subsequent governments have failed to challenge.

Furthermore, while the violence meted out to protestors does indeed raise reflections about the dictatorship tactics, it is also reflective of how Mapuche resistance is routinely criminalised. The moment Chileans mobilised against the government, their legitimate protest was a target for state institutions. By the last days of October, according to the National Institute for Human Rights in Chile, 3,535 Chileans were detained, 1,132 injured, 43 minors were maltreated, 5 killed and 19 declarations of sexual torture were recorded.

Chile’s social and political status quo has been altered. Last week, Piñera, who is facing constitutional accusations regarding the human rights violations carried out by the military and the police, stated he was open to discussing a constitutional reform. However, this week Piñera announced discussions were being held to advance a new constitution. It remains to be seen if the people’s demands will indeed be met.

These demands must be based upon the reciprocity of political support which Chileans and the Mapuche have shared since the protests started. Speaking on the anniversary of his son’s murder, Marcel Catrillanca affirmed Mapuche support for the Chilean people: “We, the Mapuche, have, supported many demonstrations and we will continue to support the Chilean people.” In light of this evident unity, it is imperative that justice for Catrillanca is not depicted solely as a Mapuche issue, but one that affects the entire Chilean nation.