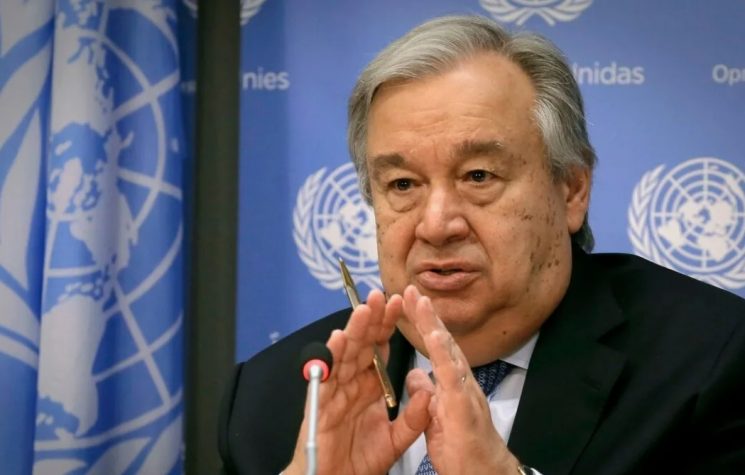

Recent events have pointed to the weakness of the United Nations in dealing with international crises. The UN is experiencing the same diplomatic inertia that doomed its predecessor, the League of Nations. The UN Secretary General is not using all the powers granted to him by the UN Charter to try to extinguish flames of civil conflict breaking out around the world, from Catalonia to Syria and Hong Kong to the British Isles.

Although the major world powers engineered the UN and its predecessor, the League, to accommodate as members only independent states, the UN Secretary General does have the power to invite non-members, whose rights of statehood or independence are contested by one or more UN member states, to address the UN Security Council to air their grievances before the world body.

On October 14, the Spanish Supreme Court ruled on the fates of 12 government leaders of Catalonia, who were criminally charged for their roles in the 2017 declaration of independence proclaimed in Barcelona, the Catalonian capital. The leaders, who were hauled off to prison in Madrid, a city viewed as the capital of a foreign entity by many Catalonians, were sentenced to between 9 and 13 years in prison for “sedition, misappropriation of government funds, and civil disobedience.” The harsh sentences for a political action are in direct contravention of the responsibilities of Spain under the European Union, Council of Europe, and European Court of Human Rights. The most severe prison sentence was meted out to Catalonia’s former Vice President, Oriol Junquera: 13 years. Eight former Catalonian government ministers received between 10 to 12 years in prison.

The handing out of the severe Franco-style prison sentences to the Catalonian leadership resulted in massive street protests in Barcelona and throughout Catalonia. A mass protest in support of the Catalonians was held in San Sebastian by Basque nationalists. Catalonian and Spanish police reacted violently to the protests in Catalonia, even resorting to the brutal clubbing of protesters and journalists, alike.

There is no question that the Spanish government, bowing to the ghost of Spain’s longtime fascist dictator, Generalissimo Francisco Franco, who, along with his Nazi German and Italian fascist allies, violently suppressed Catalonia during and after the Spanish Civil War, had acted in the extreme. In June of this year, the same Supreme Court that sentenced Junquera to 13 years in prison for abiding by the results of a popular referendum on independence for Catalonia, handed down 15-year prison sentences to five men who violently gang-raped an 18-year old woman at the 2016 Pamplona bull run. In the case of Junquera and his fellow Catalonian leaders, it was the Catalonian nation and culture that was figuratively “raped” by the Spanish Supreme Court. Yet, the “esteemed” justices saw no need to sentence themselves to 15-years in prison.

UN Secretary General António Guterres, who is from Portugal, has the authority and ability to invite the seven Catalonian leaders who fled into exile into other European nations, including former President Carles Puigdemont, to address the UN Security Council and confront before the world body the Permanent Representative of Spain to the United Nations. Guterres, more than any past UN Secretary General, should understand the bellicosity of the domineering Castilians toward other nationalities on the Iberian Peninsula. There was a time, under Franco, when the fascist Falangists wanted to annex Portugal to the Spanish state. If that had occurred, it could have been Guterres who was sentenced to 13 years in prison for Portuguese “sedition” against the Spanish state.

Similarly, after President Donald Trump reneged on US military security protection of the Syrian Kurdish inhabitants of the Rojava region of northern and eastern Syria and the Syriac-Assyrians of Gozarto in northeastern Syria and withdrew US special operations forces to make way for Turkish ethnic cleansing of Kurdish territory, Guterres could have invited the political leaders of Rojava and Gozarto to address the Security Council. There, the Kurds and Assyrians could have directly confronted the representatives of Turkey and the United States before a world audience. It is for exactly these types of situations that the UN Secretary General was invested with the powers to invite representatives of non-member states to address the Security Council.

Previously, representatives of Palestine, even before it became a non-member official observer state of the UN, were able to confront the Israeli ambassador before the Security Council. In 1975, Secretary General Kurt Waldheim invited the observers of two applicant member states – the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the Republic of South Vietnam, which had just militarily defeated the United States after a long war, to address the Council. Even though US ambassador Daniel Moynihan welcomed the two observers, Nguyen Van Luu of North Vietnam and Ding Ba Thi of the Provisional Revolutionary Government in Saigon, he cast a US veto on UN membership of the two states, which eventually merged into one, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Moynihan’s no vote was the only one cast, with Japan, the United Kingdom, China, the USSR, and France voting to admit the two states. Only Costa Rica abstained. If the North Vietnamese and Vietcong could send emissaries to the Security Council in 1975, there is absolutely no reason why Catalonia and Rojava/Gozarto cannot do the same today. The failure of the UN Security Council to do so is yet another indication of how the UN has sold itself to global corporate interests and those of the host nation, the United States.

In 1948, Secretary General Trygve Lie invited a representative of the State of Hyderabad to address the Security Council. India was threatening to invade the princely state, which did not opt to join the Indian Union after Britain granted independence to India and Pakistan. The Indian Permanent Representative argued that the representative of the Nizam of Hyderabad had no right to address the Council. However, Lie and the UN Secretariat rejected the Indian stance and no member of the Security Council questioned that decision. There is no reason why the current Secretary General cannot invite representatives of the former Autonomous State of Jammu and Kashmir, which was dissolved on the orders of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to address the Council. Similarly, representatives of the Free Territory of Trieste, citing the Treaty of Peace with Italy signed in Paris on February 10, 1947, were denied the right to bring their grievances, arising from the 1954 annexation of Trieste by Italy, before the Security Council, due mainly to pressure from the United States, Britain, and France. The US was exercising more control over the UN with a new Secretary General, Dag Hammarskjold, at the helm than it could under Lie.

The US Mission to the United Nations is mired in the past. From 1951 to 1954, the UN accepted no new members because each and every aspirant member state was subjected to Cold War rivalry politics. In some ways, the hostility toward new members was a result of policies carried over from the failed League of Nations. Those states already independent saw any newcomers as beneath recognition, either diplomatically or as a result of admission to the League or the UN. In 1920, the League rejected Liechtenstein’s application because the small principality was seen as a vassal state of Switzerland. This same policy by the UN saw the situation that between 1947 and 1955, there were almost as many full membership-desiring observer nations at the UN as there were actual full members!

Current UN members should have some empathy for those who are not recognized as states but have legitimate grievances to air before the Security Council. In 1961, Kuwait’s application to join the UN was opposed by Iraq and vetoed by the Soviet Union because it was argued that Kuwait did not possess legitimate statehood. Iraq pointed out that the Sheikh of Kuwait considered most of the 250,000 inhabitants of the territory to be foreigners. In fact, it was the US representative at a UN meeting in San Francisco in 1948 who argued that “some political entities which do not possess full sovereign freedom to form their own international policy” could still have the essential characteristics “requisite of United Nations membership.” It is because of this caveat that saw such states as Kuwait, Monaco, Andorra, Liechtenstein, and San Marino admitted as full UN members.

Before Nepal was admitted as a UN member in 1955, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru maintained that India’s northern border with China was the Himalayan mountain range. That contention placed Nepal, Sikkim, and Bhutan to the south of the claimed Indian border. Although Nepal and Bhutan eventually became UN member states, Sikkim was invaded and forcibly annexed to India in 1975. Sikkim’s request to address the Security Council was deep-sixed by US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in a Confidential April 16, 1975 State Department cable to the US embassy in New Delhi: “Our support for a Sikkimese request to have the United Nations look into the problem might be welcomed in Nepal, Pakistan, or China, this would not be productive approach. The only result would be to create new and serious bilateral problems with India, and it would run the risk of creating heightened tension in the Himalayas.”

Kissinger helped usher the era of status quo enthusiasm at both the State Department and UN. No longer would the Security Council welcome pleas from non-member delegations, whether they were from Sikkim, Western Sahara, Cabinda, and East Timor in 1975 or Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Ajaria, Transnistria, Gagauzia, or Nagorno-Karabakh in the 1990s. In fact, Secretary General U Thant believed that entities with populations smaller than 100,000 were not even viable UN member states.

Secretary General Guterres should re-adopt the policies of the first Secretary General, Trygve Lie, and extend invitations to non-member aspirant states to bring their cases before the world body. Only then, will the UN be recognized, once again, for its neutrality and universality.