Who was Portuguese Prime Minister, when Portugal, along with the other NATO mob, was bombing Belgrade? António Guterres, of course!

❗️Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

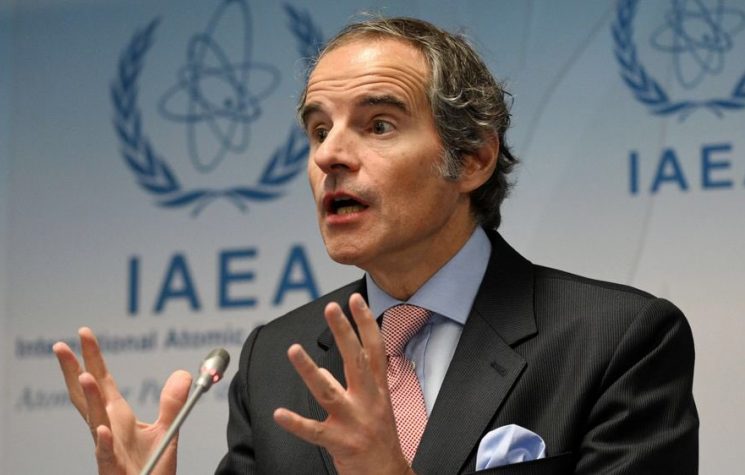

António Guterres, according to what I have read somewhere, has formally and publicly protested the fact that the people of the newly incorporated regions of Russia participate in the latter’s presidential elections. The reason, he claimed, was that it had been an illegal incorporation, based on an also illegal invasion. Russia would thus have in this case the might, Guterres argued, but she would not have on her side the right.

Does this sit well with a UN Secretary-General? It certainly does, the unaware reader will likely say. That’s precisely what the UN exists for: to show everyone that, beyond might, irreducible to it, there is always (and there will be) the right.

The problem with this – formally impeccable – argument resides, however, elsewhere.

Do you remember Kosovo? It was occupied by NATO in 1999, after this alliance bombed the then Yugoslavia, on various pretexts that later were revealed to be false, forcing it (without a UN mandate, by sheer military might) to withdraw from that territory. Yugoslavia held out for almost three months of relentless bombardment, but eventually withdrew, albeit grudgingly and only against written assurances that Kosovo would remain Yugoslav territory, only provisionally occupied: “we didn’t give away Kosovo, we don’t give away Kosovo”, Slobodan Milosevic then declared publicly.

Kosovo was part of a Yugoslav republic, Serbia, and remained so even when this and the other remaining Yugoslav republic, Montenegro, later legally ‘divorced’, thus ending the very existence of the ‘once upon a time’ Country of the South Slavs.

Serbia does not recognize the right to secession of her provinces, and so she did not recognize the secession of Kosovo when this territory subsequently (in 2008, still under NATO occupation and without holding a referendum with that purpose) proclaimed its independence. She complained about this to the International Court of Justice, but the ICJ did not grant the Serbian complaint, arguing that, while it was true that on the latter’s side was the UN’s principle of protection of the integrity of states’ borders, on the side of Kosovar independence was the also UN’s principle of the defense of peoples right to self-determination.

That being the case, and although admittedly in a situation of mon coeur balance, the august Court decided by a majority to give the right to Kosovo’s independence, and the wrong to Serbia. The rejection of a region’s independence could be valid internally, but not internationally. Was the secession of Kosovo illegal from the point of view of Serbian law? Perhaps. But not, the ICJ declared, from the point of view of international law.

Now, with things admittedly at this point, the obvious question is: have Crimea, the Donbass, plus the other two provinces of Novorossiya, legally seceded from Ukraine? From Kiev’s point of view, of course not. But from the point of view of international law? When faced with the problem of the secession of countries de facto in a colonial situation, but formally only provinces of another (as was the case with the then Portuguese overseas provinces in Africa), the UN had already decided, in 1970, that the decisive criterion was the existence or not of negative discrimination against certain groups. If the Portuguese state practiced negative discrimination against African ‘indigenous’ people, this would be an irrefutable indication of colonialism, even if the Portuguese Constitution of the time did not openly proclaim it. Therefore, Angola and Mozambique would have the right to secede. If, on the other hand, it was a question of territories where the populations enjoyed the same rights as the ‘normal’ nationals of their respective countries, such as the Corsicans vis-à-vis the other French, or the Sardinians in relation to the other Italians, there would be no right of secession. Corsica and Sardinia would therefore not have the right to secede from France and Italy, respectively.

The point is that, precisely, Kosovo was not the target of any derogatory treatment by Serbia. On the contrary, there was positive discrimination, with the right to use Albanian as a regional co-official language, just as it is today in Spain with Basque, Galician and Catalan in the Basque Country, Galicia and Catalonia, respectively. And yet, the ICJ ruled against Serbia’s claim! That is, giving an additional right to the centrifugal political tendencies, when compared to the position of the UN General Assembly back in 1970…

Given this, the question inevitably arises: have the inhabitants of the Donbass, who revolted and organized secessionist referendums as early as 2014, and since then saw the Russian language banned, and were the target of indiscriminate bombardment by Kiev’s troops and paramilitary, and suffered all kinds of other atrocities, not much more right to secession than the Kosovars – to whom, for example, the use of Albanian had never been forbidden by Belgrade? On the contrary, the entire Albanian cultural legacy was always carefully protected by Yugoslavia’s emphatically multi-ethnic Constitution, and the ethnic Albanian population benefited from various forms of positive discrimination. And yet, the ICJ rejected Serbia’s complaint!

And if this is indeed so, if the ICJ is more pro-secession now than the UN was back in 1970, what conclusion can be drawn about the secessionist regions of Ukraine, and the legality or illegality of their secession from Kiev, even without consulting the ICJ?

And, in that case, how to assess these recent ‘noble’ public statements by António Guterres?

Oh, by the way… I didn’t mention it before and so you wouldn’t know it, but I can add it now, in case you’re interested: who was the Portuguese Prime Minister in 1999, when Portugal, along with the other NATO mob, was bombing Belgrade and the rest of Yugoslavia? Why, António Guterres, of course!

And what prime minister did we the Portuguese people have in 2008, when Kosovo proclaimed its independence? José Sócrates. And did Portugal recognize Kosovo? Yes, of course we did (unlike Spain, for example, I wonder why…). And does Portugal maintain this recognition? Well, of course! (In the meantime, let it be noted in passing, “the splendor of Portugal” was also restated in 2003, with Prime Minister Durão Barroso’s organization of the celebrated Azores Summit, aiming at the Collective West’s invasion of Iraq. But that’s another story).

Does anyone still have doubts about the ‘logic’ or the ‘righteousness’ of the international conduct of Portugal and of most famous Portuguese?