Is the prospect of looming global recession merely an economic matter, to be discussed within the framework of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 – which is to say, whether or not, the Central Bankers have wasted their available tools to manage it? Or, is there a wider pattern of geo-political markers that may be deduced ahead of its arrival?

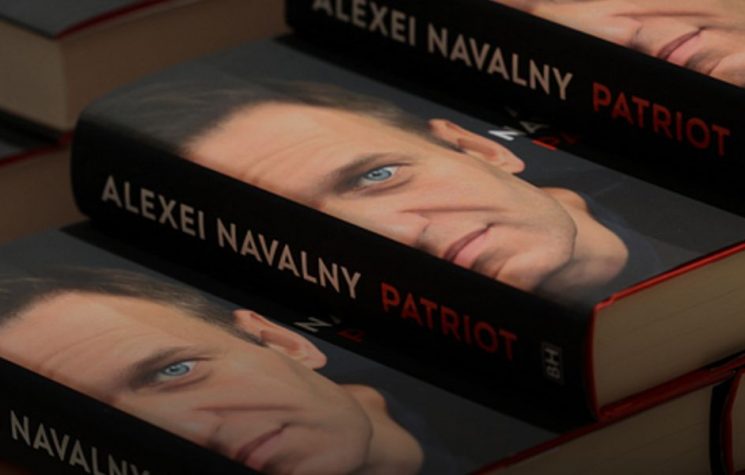

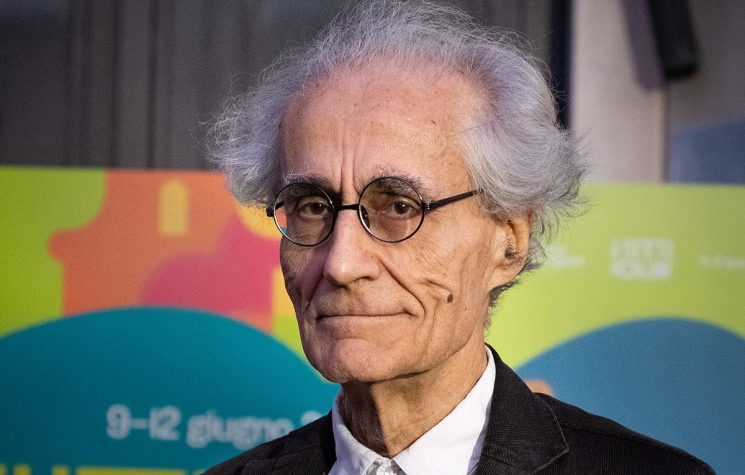

Fortunately, we have some help. Adam Tooze is a prize-winning British historian, now at Columbia University, whose histories of WWII (The Wages of Destruction) – and of WWI (The Deluge) tell a story of 100 years of spiraling; ‘pass-the-parcel’ global debt; of recession (some ideologically impregnated) , and of export trade models, all of which have shaped our geo-politics. These are the same variables, of course, which happen to be very much in play today.

Tooze’s books describe the primary pattern of linked and repeating events over the two wars – yet there are other insights to be found within the primary pattern: How modes of politics were affected; how the idea of ‘empire’ metamorphosed; and how debt accumulations triggered profound shifts.

But first, as Tooze notes, the ‘pattern’ starts with Woodrow Wilson’s observation in 1916, that “Britain has the earth, and Germany wants it”. Well, actually it was also about British élite fear of rivals (i.e. Germany arising), and the fear of Britain’s élites of appearing weak. Today, it is about the American élite fearing similarly, about China, and fearing a putative Eurasian ‘empire’.

The old European empires effectively ‘died’ in 1916, Tooze states: As WWI entered its third year, the balance of power was visibly tilting from Europe to America. The belligerents simply could no longer sustain the costs of offensive war. The Western allies, and especially Britain, outfitted their forces by placing larger and larger war orders with the United States. By the end of 1916, American investors had wagered two billion dollars on an Entente victory (equivalent to $560 billion in today’s money). It was also the year in which US output overtook that of the entire British Empire.

The other side to the coin was that staggering quantity of Allied purchases called forth something like a war mobilization in the United States. American factories switched from civilian to military production. And the same occurred again in 1940-41. Huge profits resulted. Oligarchies were founded; and America’s lasting interest in its outsize military-security complex was founded.

Wilson was the first American statesman to perceive that the United States had grown, in Tooze’s words, into “a power unlike any other. It had emerged, quite suddenly, as a novel kind of ‘super-state,’ exercising a veto over the financial and security concerns of the other major states of the world.”

Of course, after the war – there was the debt. A lot of it. France “was deeply in debt, owing billions to the United States and billions more to Britain. France had been a lender during the conflict too, but most of its credits had been extended to Russia, which repudiated all its foreign debts after the Revolution of 1917. The French solution was to exact reparations from Germany”.

“Britain was willing to relax its demands on France. But it owed the United States even more than France did. Unless it collected from France—and from Italy and all the other smaller combatants as well—it could not hope to pay its American debts.”

“Americans, meanwhile, were preoccupied with the problem of German recovery. How could Germany achieve political stability if it had to pay so much to France and Belgium? The Americans pressed the French to relent when it came to Germany, but insisted that their own claims be paid in full by both France and Britain. Germany, for its part, could only pay if it could export, and especially to the world’s biggest and richest consumer market, the United States. The depression of 1920 killed those export hopes. Most immediately, the economic crisis sliced American consumer demand precisely when Europe needed it most.”

Wars are frequently followed by economic downturns, but in 1920-21, US monetary authorities actually sought to drive prices back to their pre-war levels through austerity. They engineered a depression. They did not wholly succeed, but they succeeded well enough. When the US opted for massive deflation, it thrust upon every country that wished to return to the gold standard, an agonizing dilemma. Return to gold at 1913 values, and you would have to match US deflation with an even steeper deflation of your own – and accept mass unemployment as the consequence – or devalue.

Britain actually chose the course of deflation and austerity. Pretty much everybody else however, chose to devalue their currency (relative to gold), instead. But American leaders of the 1920s weren’t willing to accept this outcome. They did not want their industry and markets disturbed by a flood of cheap French and German products. In 1921 and 1923 – just as today in respect to China – America raised tariffs, terminating a brief experiment with freer trade undertaken after the election of 1912. “The world owed the United States billions of dollars, but the world was going to have to find another way of earning that money than selling goods to the United States”.

That way was found: (you can guess it) – more debt. Germany resorted to the printing press. (Printing money was the only way Germany could afford to rearm in anticipation of the WWII sequel to the First WW). The 1923 hyper-inflation that wiped out Germany’s savers, however also tidied up the country’s balance sheet. Post-inflation Germany looked like a very creditworthy borrower.

“Between 1924 and 1930, world financial flows could be simplified into a daisy chain of debt. Germans borrowed from Americans, and used the proceeds to pay reparations to the Belgians and French. The French and Belgians, in turn, repaid war debts to the British and Americans. The British then used their French and Italian debt payments to repay the United States, who set the whole crazy contraption in motion again. Everybody could see the system was crazy.” Only the United States could fix it. It never did.

Why? Because “[a]t the hub of the rapidly evolving, American-centered world system, there was a polity wedded to a conservative vision of its own future” [as global hegemon], Tooze opines.

The flip side to this fixation with a dollar “as good as gold” was not just the inter-war hardship of a war-ravaged Europe, but also the threat of American markets flooded with low-cost European imports: German steelmakers and shipyards underpricing their American competitors with weak marks. Such a situation also prevailed after World War II when the US acquiesced in the undervaluation of the Deutsche mark and yen precisely to aid German and Japanese recovery.

Fast forward to today – and here lies the root of Trump’s economic Zeitgeist. The US fear has returned in a new iteration: America’s global primacy is being overtaken, this time by China.

The austerity of the 1920s, and the depression that followed, eviscerated governments throughout Europe. Yet the dictatorships that replaced them were not, as Tooze emphasizes in The Wages of Destruction, reactionary absolutisms; rather, they aspired to be modernizers. And none more so, than Adolf Hitler. Tooze writes: “The originality of National Socialism was that, rather than meekly accepting a place for Germany within a global economic order dominated by the affluent English-speaking countries, Hitler sought to mobilize the pent-up frustrations of his population to mount an epic challenge to this order.

Hitler dreamed of conquering Poland, Ukraine, and Russia as a means of gaining the resources to match those of the United States, Tooze argues. “The vast landscape in between Berlin and Moscow would become Germany’s equivalent of the American West”. Hitler’s original aim, Tooze suggests, was more that of a highly modernised and industrial first Reich – a Carolingian ‘empire’, such as that instigated by the Franks after the Fall of Rome.

Although configured differently, the German National Socialist dream of a ‘modern’ Caroligian empire still underpins an EU vision of Europe today, as its lineal descendent.

After WWII, a weakened, and chastened Europe definitively turned away from raw ‘power’; or to put it a little differently, it moved beyond power towards a different style of ‘empire’. Still Carolingian in essence – that is, with a centralized command (in the Frankish style), overseeing a self-contained world of laws and rules and tightly regulated cooperation.

But, with the post-war ethos of ‘never again’, it evolved into a millenarian project, grounded in Kant’s ‘Perpetual Peace’ – and of his ‘compelling’ logic of global governance as the only solution to the brutal politics of Hobbesian anarchy, (though Kant also feared that the “state of universal peace” made possible by world government would be an even greater threat to human freedom than the Hobbesian international order, inasmuch as such a government, with its monopoly of power, would become “the most horrible despotism”).

So, Europe lives a “postmodern system” that does not rest on a balance of power, but on “the rejection of force” and on “self-enforced rules of behaviour”. In the “postmodern world,” wrote Robert Cooper (himself a senior EU official): “raison d’état and the amorality of Machiavelli’s theories of statecraft … have been replaced by a moral consciousness” in international affairs.

The result is a paradox. The US solved the ‘Kantian paradox’ for the EU of its Liberal rejection of power politics through providing security, which rendered it unnecessary for Europe’s supranational government to provide it. Europeans did not need power to achieve peace, and neither have they needed power to preserve it.

It is precisely this paradox on which Trump has ‘zeroed-in’, in order to mobilise his base towards a new view of Europe, as a predatory trade rival. The US, faced by a rising China, is retrenching into a Hobbesian world where hard ‘power’ is paramount, and will thus be increasingly unsympathetic to European liberal, moral-concern narratives.

Here is the point: The EU initially would never have come into being, without America’s covert political engineering. And Europe was, (and still is), consequently founded on the premise of unreserved US benignity towards the EU. But that key premise no longer holds: Can a Europe on the cusp of recession successfully manage to balance away from a US now focused on trade war toward Eurasia?

What might a looming recession then portend? The pendulum will (almost certainly) now swing to the other extreme from the 1920s. Trump is a zero-interest, bail-out man. But this extreme swing in the opposite direction, however, is likely induce similar rounds of ‘daisy-chain’ sloughing-off of toxic debt onto someone – anyone – else; of competitive devaluation, and attempted deflation-export.

A substantive global recession may set the whole ‘crazy debt contraption’ in motion again. But this time, amplified by a collapsing oil price, toppling Middle Eastern states, etc. Everybody can see the system is crazy. The United States could fix it, but it never will.

It has weaponised the financial system so thoroughly that the US will never yield on the dollar status. The question is, do China and Russia have the political will – and capability – to assume the task of mounting a different financial order?

Why did the US not fix the system in the inter-war years? Because, Tooze tells us (in coded terms), the system had proved a gold-mine for the weapons-manufacturing oligarchs, and America was mightily taken with the unfolding prospect of its leading the world: the ‘American century’ ahead.

Also, before WWI, Tooze writes in The Deluge, the ability of the US to act was hindered by its ineffective political system; dysfunctional financial system, and uniquely violent racial and labor conflicts. “America was a byword for urban graft, mismanagement and greed-fuelled politics, as much as for growth, production, and profit”.

Well the two ‘world wars’ – as principal weapons’ provider – did not make that situation much better. Oligarchic fortunes and influence blossomed. The interwar years saw the intersection of certain oligarchic interests with that of organized crime in America, and WWII saw the linking of the Italian mafia into US foreign operations – and thus to the US political class.

In 1916, the US output surpassed that of the entire British Empire. Ninety-eight years later, US output supremacy (in PPP terms) came to an end. China surpassed America. Will a more fractured, increasingly belligerent US domestic polity be able to fix the financial order, as the latter careers from one extreme to a disordered, sanctioned and tariffed other? America most likely, will once again be wedded to a “conservative” [i.e. Hobbesian] vision of pursuing its own future.