The idea that the Middle East no longer represents a central strategic region, reducible to a limited conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, seems overly optimistic.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

New perspectives

The peoples of the Middle East are watching closely to see whether Washington really intends to reduce its involvement in the region or whether, as with the four previous administrations, the government of U.S. President Donald Trump will also end up trapped in the quicksand of the Middle East. Beyond the high-sounding slogans that have accompanied various American presidencies, the problems in the area have progressively worsened, becoming increasingly complex, in parallel with the increase in U.S. interference.

Today, the American administration invokes the principle of “America First,” proclaiming its rejection of interventionism, state reconstruction, and endless wars. However, it has not given up on its ambition to shape the global order, as demonstrated by the publication of the National Security Strategy, which proposes a strategic redefinition of the Middle East with the aim of preventing the rise of any dominant power in the region. It remains to be seen whether this new attempt will be successful, whether influential states will accept the American formula, and whether local populations will tolerate regional crisis management that serves only Washington’s interests. Many questions remain unanswered, and only time will tell the outcome of Trump’s gamble, which appears to be yet another American experiment in the Middle East.

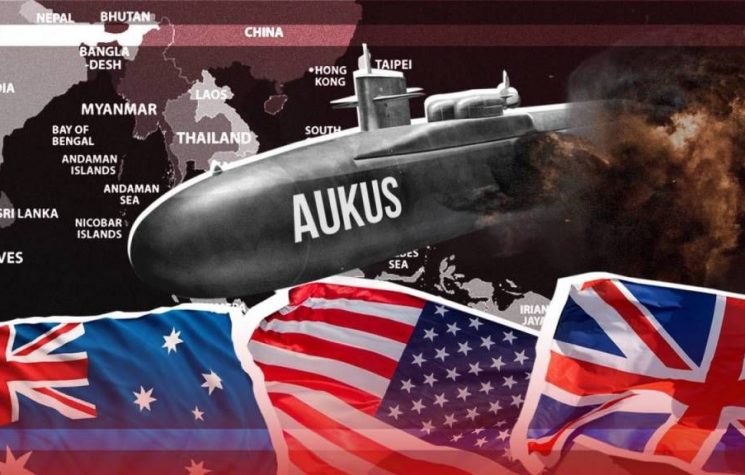

The White House document confirms that the Middle East is no longer the central element of U.S. strategic priorities. Washington’s attention is now shifting to the Western Hemisphere and the Indo-Pacific, identified as the main theaters of global geopolitical and economic competition.

According to numerous analysts, this decision marks a significant break with decades of American foreign policy, during which the Middle East has occupied a position of absolute importance. This reorientation raises profound questions about the consequences of this change and the possible end of what can be defined as the “Middle East era” of U.S. strategy.

Furthermore, this shift casts a shadow over the future of regional conflicts, as a security vacuum resulting from American disengagement could encourage further escalation, undermine prospects for peace, and increase the risk of further wars.

According to several regional experts, the strategy clearly states that the Western Hemisphere and the Indo-Pacific are now the main areas of global competition, while the Middle East is relegated to an area of “selective engagement” based on mutual and limited interests.

Other observers, however, point out that this would not be a total withdrawal, but rather a form of calibrated disengagement. The United States would remain present whenever its economic or intelligence interests were threatened, but would avoid fighting wars on behalf of third parties.

According to this interpretation, the reduction in the centrality of the Middle East does not imply the end of sanctions or military operations against states considered dangerous to American interests. Rather, it signals a willingness to no longer sacrifice human and financial resources to contain regional conflicts that do not directly affect U.S. national security.

This line is consistent with statements by numerous Washington officials, who have repeatedly highlighted the enormous costs incurred by America in terms of money and human lives, arguing that the time has come for allies to take on greater responsibility, while the United States will only intervene in the event of direct threats to its vital interests.

Something is changing

In a sense, it is not incorrect to say that the downgrading of the Middle East in the 2025 security strategy does not represent a simple reordering of priorities, but amounts to a veritable declaration of the end of the Middle East era in American politics, replaced by competition with China and Russia in other theaters. Such an approach will inevitably create a security vacuum that is bound to fuel new tensions.

In particular, Israel will have to decide what to do about the new American strategy, which some have already interpreted as a license to sweep the Palestinian region, extending the hegemony of the Greater Israel project to surrounding countries. Israel will undoubtedly continue to benefit from U.S. logistical and intelligence support, and no one will limit its operations, even if it crosses certain red lines. This could trigger a new arms race in the region, with each country committed to strengthening its military capabilities for self-defense.

It is also true that the new American strategy prioritizes the defense of national territory—borders, airspace, and internal security—drastically reducing the global commitments that have characterized U.S. policy since the Cold War.

The Middle East, once at the center of American strategy, is now relegated to a secondary region, while competition with China in the Pacific assumes the role of the major geopolitical battlefield of the century. Washington will approach the Middle East primarily based on mutual economic interests, abandoning the massive military commitments of the past. This approach represents, in Washington’s view, the concrete application of the “America First” principle, which links national security to internal economic stability, the fight against immigration and drug trafficking, and the reduction of military spending in the Middle East in favor of American industry.

We can summarize by saying that the National Security Strategy does not herald a more just or peaceful Middle East, but rather a more rigid, ruthless, and at the same time more transparent regional order. For the first time in decades, the United States is treating the Middle East as political realism suggests: an important, but not vital, region whose stability matters only to the extent it impacts fundamental American interests. It is not simply a political document, but the theoretical manifesto of a new approach that rejects the post-1991 idea of the United States as the indispensable guarantor of the global liberal order. In its place emerges a disciplined realism, which evaluates every external engagement based on a single criterion: the direct benefit to American security, prosperity, and way of life.

In conclusion, Washington may succeed in preventing the rise of a hegemonic power in the Middle East, but imposing a regional order built exclusively on American interests and directives is neither a given nor guaranteed.

The idea that the Middle East no longer represents a central strategic region, reducible to a limited conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, seems overly optimistic. Denying the region’s energy importance, the competition between great powers, and the potential for conflict to spread is not the same as eliminating them.

Denial or wishful thinking does not create reality. The Middle East will continue to be crucial to the international system, and the Palestinian question will remain a constant and unresolved presence that will continue to weigh on all actors involved. And someone, sooner or later, will hold the United States accountable.