Ukraine’s future leaders will need to be driven by pragmatism and realism

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

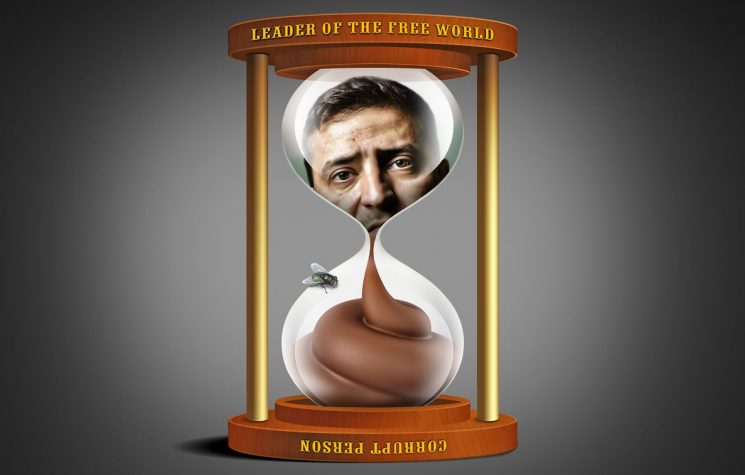

The political tide in Kiev has started to turn against Volodymyr Zelensky. Since the war started, he has enjoyed a significant majority of support in Ukraine’s political establishment. The latest corruption scandal to hit his inner circle may represent the beginning of the end of his rule.

Since war broke out in February 2022, Volodymyr Zelensky has built a global brand as the small man of good morals who stood up to big Russia. Applauded in western capitals, feted at home, few have dared to criticise his approach.

Zelensky’s rule hasn’t been completely without opposition. He sanctioned former President Petro Poroshenko and other Ukrainian oligarchs in February 2025, shortly after President Trump assumed office, and shortly before he was famously criticised in the Oval Office by the new U.S. President. This seems to have been a politically motivated move to undercut potential political rivals ahead of a shift in U.S. policy towards the war. In other words, silencing dissenting voices who might come out in support of a U.S.-led effort to end the war quickly. After his dressing down in DC, Zelensky went on a European charm offensive that led successfully to a hardening of the EU and NATO position towards continuing the war, stymying Trump’s peace moves in the process. Other sanctions have followed of political oppositionists since that time.

But as the war drags on, as Ukrainian losses mount and with the bastion of Pokrovsk on the verge of falling, the war with Russia looks increasingly unwinnable by Ukraine. For impartial observers such as myself, the war has always been a folly that Ukraine could never win. Yet, Zelensky’s de facto nationalisation of the media in Ukraine has also limited scope domestically to criticise his government’s policy. And western mainstream media has become so invested in the total victory delusion about Russia, that voices of reason have been pushed to the margins.

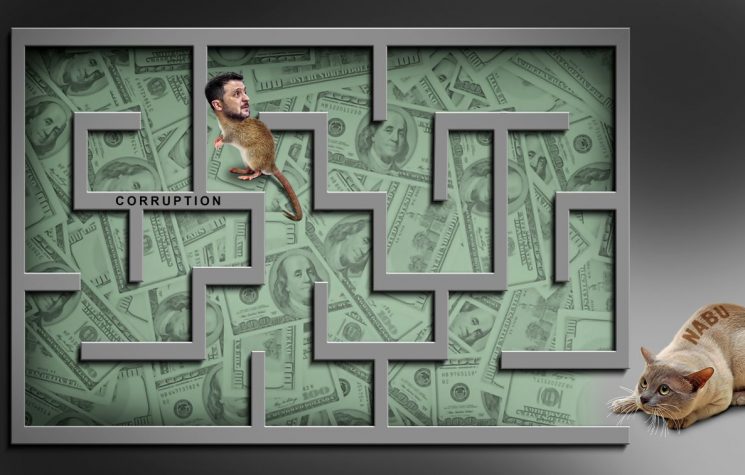

Zelensky’s nakedly, in my opinion, self-interested move in July to cripple independent anti-corruption bodies such the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) was a moment of political peril for him personally. He managed to navigate the public backlash in Ukraine by backing down and blaming others.

Yet, this recent corruption scandal, related to one of his closest allies orchestrating an industrial-scale skimming off of $100 million from Ukrainian energy companies, refuses to go away. Suggestions of widespread corruption in Zelensky’s inner circle has been circling for most of the war and it will prove harder for him to distance himself from it, nor indeed, to show he is not implicated in some way. And on the basis that the war has been sustained through hundreds of billions of dollars in foreign aid, it will be increasingly difficult to separate the continuance of the war and the continued flood of foreign money, upon which the corruption of Zelensky’s regime has in part been built.

That may help to explain why, for the first time, more conventional Ukrainian politicians have started calling in a more concerted way for change. A prominent Ukrainian Member of Parliament, and leader of the Golos Political Party, Kira Rudik, has come out this week on X to say ‘I haven’t criticised Zelenskyy since the beginning of the war – but now it is outrageous. Corruption in the closest circle, in the Government, is destroying the trust of our people and our allies. We need a new government and a new parliamentary coalition.’ On 18 November, she posted that MPs had blocked the rostrum in Ukraine’s parliament and claimed that nearly 50 MPs had already signed a motion to fire the government.

Politicians across Ukraine will be watching the polling numbers which show most citizens now support a negotiated end to the war and will be trying to position themselves as counterpoints to Zelensky, who has staked his campaign on the impossible notion of a strategic defeat of Russia. This may have prompted Zelensky’s visit to Turkey on 19 November in a bid to ‘intensify’ peace talks.

However, it has never looked remotely likely that Zelensky was sincere about bringing the war to an end and I am not convinced he is now. Zelensky’s desire to keep fighting has been so strong, that he would now find it difficult to position himself as a peacemaker.

I am therefore of the view that we are starting to enter the endgame for Zelensky’s grip on power, although he may well stand for re-election, as and when elections are called. Though I suspect increasing numbers of people in Ukraine see Zelensky as the problem, and not the solution.

It is impossible to imagine any credible Ukrainian oppositionist positioning themselves as the putative future President who stiffens western financial support, at a time when the U.S. purse is closed and European pockets are empty. Keeping calm and carrying on with the failed policies of the past four years probably won’t be on the menu as and when political campaigning gets into top gear in Ukraine. So, new ideas will be needed.

Oleksiy Arestovych, a key Zelensky adviser at the start of the war, went into exile in January 2024, having criticised Zelensky’s approach to the war, sketched out his vision for Ukraine at that time in an interview with UnHerd.

Ukraine needed to be an independent country, he said, and would never be part of Russia. Yet, Ukraine needed to accept the reality that it would never join NATO, because of the all-out war this would provoke with Russia, which continues to this day. He recognised that a bigger discussion on Europe’s security architecture was needed that included NATO and EU allies, but also Russia (and Belarus), which he argued also needed to feel secure in its borders.

Rather than trying to be west or east, Ukraine should embrace its poly-cultural nature, not trying to force a uniquely Ukrainian ethnic and linguistic identity on its people, but accepting the (according to him) 38 different ethnic groups and even larger number of languages. Of course, a significant constituent of that is that large number of ethnic Russians and Russian speaking peoples who continue to live in Ukraine today.

Arestovych argued that Ukraine would never be able to take back all of the Donbas, and probably also Crimea. And he confirmed that an Istanbul peace agreement was 90% complete and at the stage where Zelensky could have negotiated it with President Putin.

Read the interview and you won’t easily find anything that marks Arestovych out as pro-Russian or a Kremlin crony, to use the popular insult levelled at anyone who disagrees with the direction of Ukraine’s policy since the war began. Rather, his is a voice of pragmatism and realism. Not trying to create a magical world for Ukraine which will never exist, but dealing with the facts on the ground, and seeking ways for Ukraine to be independent and on acceptable terms with other nations including, yes, Russia.

I am not speaking in favour of Arestovych’s candidacy as others will no doubt step forward with their ideas, including Kira Rudik, when the time is right. But it’s clear to me that, as we enter the endgame for Zelensky, pragmatism and realism are very much needed by Ukraine’s future leaders, if that country is to rebuild, prosper and heal.