The question plaguing the US is: expand and enter the commercial game, or restrict, block, prevent? And if so, on what timeline?

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Where the compass points

The Arctic. This single word encapsulates the new energy and trade route that is rapidly changing the plans of entire countries and causing considerable concern in the United States of America. That is why it makes sense to study the perspective, to understand not only what the current concerns are, but also to predict what future moves will be. We will do this in several articles, to try to capture all the details of the US vision.

First, the general context: the Arctic region is warming at a rate almost four times faster than the global average. According to climate projections, in the next ten to thirty years, the Arctic Ocean could become ice-free during the summer for short periods, creating a seasonally navigable passage connecting Asia and Europe via the North Pole. A seasonally ice-free Central Arctic Ocean (CAO) would allow maritime trade to expand further north than ever before. Gradually, trans-Arctic shipping could move to ice-free international waters, tourism to the North Pole could become more frequent, and fishing activities could also extend northward.

However, uncertainty about how Arctic nations will respond to these new conditions and the increased accessibility of Arctic waters increases the likelihood of a greater military and law enforcement presence in the CAO. In this evolving strategic, commercial, and legal environment, global powers may increasingly seek to assert their influence and expand their presence, with potential implications for the security of the United States and other Arctic nations.

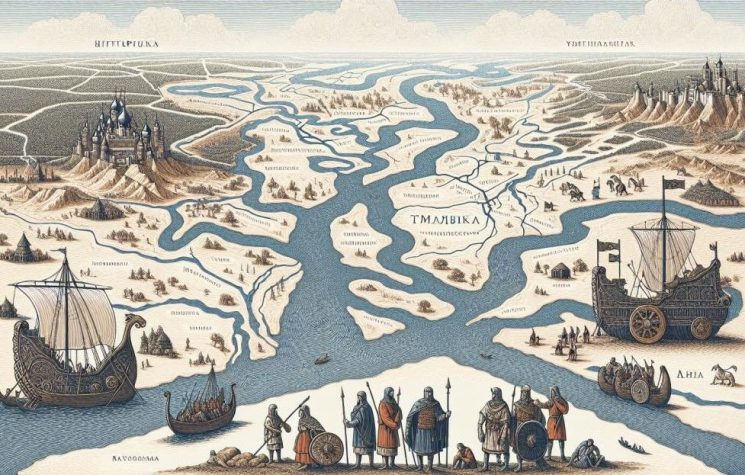

Unlike other Arctic routes, such as Russia’s Northern Sea Route (NSR) or Canada’s Northwest Passage (NWP), this new route, often called the Transpolar Route (TSR), would primarily traverse international waters, which have so far seen only minimal human activity, limited to scientific missions, symbolic expeditions, and rare tourism initiatives.

Beyond its symbolic importance, the TSR represents a broader geophysical transformation: the gradual opening of the Central Arctic Ocean to seasonal commercial operations and surface military operations. The CAO refers to the area of the Arctic Ocean consisting exclusively of international waters (or high seas), surrounded by the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of Canada, Denmark (via Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Norway, Russia, and the United States. These EEZs extend into the peripheral or marginal seas of the CAO, such as the Greenland Sea and the Kara Sea. The CAO covers approximately 2.8 million square kilometers, an area comparable to the size of Argentina.

Historically, the CAO has remained entirely or almost entirely covered by sea ice throughout the year. However, in 2024, Arctic sea ice extent fell to 4.28 million square kilometers in September, the month of minimum annual ice cover. Although the CAO itself remained covered by ice, that year marked the seventh lowest ice extent ever recorded in September, and the eighteen lowest extents have all occurred in the last eighteen years.

A seasonally ice-free CAO would allow trade and shipping to extend further north than ever before. Trans-Arctic shipping routes could gradually shift toward ice-free international waters to bypass national EEZs, and ships carrying Arctic minerals or hydrocarbons could take advantage of shorter, more direct routes to global markets. Tourist expeditions to the North Pole could become increasingly frequent, while fishing activity could also migrate northward. The Agreement for the Prevention of Unregulated Fishing on the High Seas in the Central Arctic Ocean (CAOFA) will expire in 2037, potentially paving the way for contentious debates over access to ecologically fragile and newly exposed fishing grounds.

Uncertainty about how Arctic states will respond to these developments—and to the broader increase in marine accessibility near the boundaries of their EEZs—increases the possibility of intensified military and law enforcement activities in the CAO. At the same time, global powers may seek to expand their presence and exert greater influence in this rapidly evolving strategic, commercial, and legal environment, with implications for the security of the United States and other Arctic nations.

The question plaguing the US is: expand and enter the commercial game, or restrict, block, prevent? And if so, on what timeline?

The commercial problem: where to go?

Let’s start with trade routes, the first sticking point for the American establishment.

Sustained commercial activity is already present in the Arctic at latitudes lower than the CAO, such as oil and gas transport along the Northern Sea Route or mining in northern Canada, Greenland, or Sweden. As accessibility increases, some of these activities may extend further north. Other activities that have been rare in the Arctic until now, such as freight transport, may be diverted from non-Arctic routes.

The extent to which these activities develop is key to understanding whether the CAO will become a significant traffic hub or whether its contribution to global trade will remain marginal. In this chapter, we analyze the expected use of the CAO for commercial shipping, fishing, extractive industries (oil, gas, minerals), and other activities, such as scientific research, tourism, wind energy, and submarine cables, highlighting for each the factors that could favor or limit its development.

Between 2013 and 2023, Arctic maritime traffic increased by 37% thanks to longer sailing seasons due to reduced ice and the exploitation of Arctic resources such as natural gas on Russia’s Yamal Peninsula or iron in Canada’s Nunavut. Currently, commercial shipping in the Arctic takes place seasonally via the 689NSR and, to a lesser extent, the Northwest Passage (NWP). To understand how much of this traffic could be redirected to the North Pole, it is necessary to assess whether the Transpolar Sea Route (TSR) offers greater economic advantages than these two existing routes. The choice of route for commercial shipping depends mainly on the overall costs of the voyage, which are influenced primarily by the distance traveled (which affects operating and labor costs) and fuel costs per unit. From this perspective, Arctic routes offer significant advantages over traditional routes: the NSR is about 40% shorter than the route through the Suez Canal from Northeast Asia to Europe, while the TSR is approximately 15% shorter than the NSR (and 25% shorter than the NWP). A shorter route generally means lower fuel consumption and reduced overall operating costs. These savings increase with the latitude of the ports of departure or destination; for example, a trip to Rotterdam via the NSR is approximately 20% shorter from Yokohama than from Hong Kong.

In addition, the greater depth of the TSR overcomes the draft limitations of the NSR and NWP, allowing passage to ships with larger cargo capacities than those currently permitted in the shallow straits of the NSR (12.5 meters near the New Siberian Islands) and NWP (less than 10 meters in some places). This lack of restrictions represents an advantage in terms of economies of scale for the TSR, increasing its attractiveness for the transport of large cargoes such as oil, minerals, and grain, commodities that do not depend on just-in-time delivery times and do not require intermediate markets, which are often absent along Arctic routes.

As the region warms and longer ice-free seasons become the norm, the CAO will become progressively more accessible. Although the NSR and NWP are also becoming increasingly usable, the expected increase in accessibility for these routes will be less pronounced than for the CAO, which is already partially accessible seasonally. With the retreat of multi-year ice, often replaced by thinner first-year ice, more types of ships—including those without special reinforcements—will be able to transit the CAO, reducing the need to invest in highly reinforced ships and decreasing fuel consumption per nautical mile. Climate models predict that by mid-century, the TSR will be the most technically accessible trans-Arctic route on more summer days than any other route, suggesting a possible marginalization of the NSR in favor of the TSR in the coming decades. Such a change will not only affect the September ice minimum, but will gradually extend into early summer and late autumn, expanding the overall operating season in the CAO. The progression may not be uniform: some years may experience more intense ice due to natural variability, highlighting the inherent uncertainty of the climate system, despite the high certainty of the long-term trend.

The Transpolar Sea Route (TSR) could become an attractive alternative shipping route for global traffic, due to geopolitical instability and congestion along traditional routes. Strategic points such as the Strait of Malacca, the east coast of Africa, and Bab al-Mandab between the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean are areas prone to piracy or political tensions that can force ships to take long and costly detours, such as the passage around the Cape of Good Hope. Similarly, artificial canals such as Suez and Panama impose physical limits on ship draft and the number of daily transits, while the continued construction of ever-larger ships exacerbates the capacity problem. In the CAO, on the other hand, there are no significant draft restrictions, offering a potential advantage for large cargo ships.

From an economic standpoint, the TSR could reduce transit costs by avoiding high tolls such as those charged by the Suez Canal, estimated at over $350,000 per ship in 2016 and rising in subsequent years, and the often opaque tariffs of the NSR, where in addition to tolls, icebreaker support and notification to the Russian authorities are required. By not requiring tolls or communication with the authorities of a coastal state, the TSR may appear more convenient. However, the decision to shift traffic will also depend on geopolitical factors and the willingness of companies to interact with Russia, an element that has so far limited the use of the NSR by external operators.

Despite the potential savings, the TSR route presents significant environmental and operational risks. The presence of floating ice, ice ridges, glacial icebergs, polar storms, and reduced visibility, combined with limited port infrastructure and insufficient satellite coverage, makes navigation complex and dangerous. The use of icebreakers can mitigate some risks, but imposes limitations on ship width and can reduce the relative draft advantage of the TSR. In addition, companies face high insurance costs related to distance from ports, ship type, ice class, and crew experience. Added to these are expenses related to specific technical characteristics required for polar operations, such as reinforced hulls and powerful engines, in compliance with the IMO’s Polar Code, which is mandatory for all ships operating in polar areas.

These factors make the TSR less attractive for traditional containerized transport, which depends on fixed times and just-in-time supply chains. The absence of intermediate ports along the route means that economic benefits are mainly achievable on direct port-to-port routes, limiting flexibility compared to ‘shuttle’ shipping models, where ships visit multiple ports along a journey. Currently, this is reflected in the commercial use of Arctic routes, which remains predominantly linked to the transport of resources extracted in the Arctic to importing markets. In 2022, while nearly 24,000 ships transited the Suez Canal, only 1,661 ships operated in the area covered by the Polar Code, 81% of which belonged to Arctic states.

Despite the limitations, TSR could become more viable thanks to technological innovations. The use of artificial intelligence and machine learning systems to predict ice movement and optimize routes could reduce risks and uncertainties, increasing the safety and efficiency of voyages in the CAO. The TSR therefore represents a potential strategic and economic opportunity, although its full adoption will depend on the balance between economic benefits, environmental and operational risks, and geopolitical factors.

[To be Continued…]