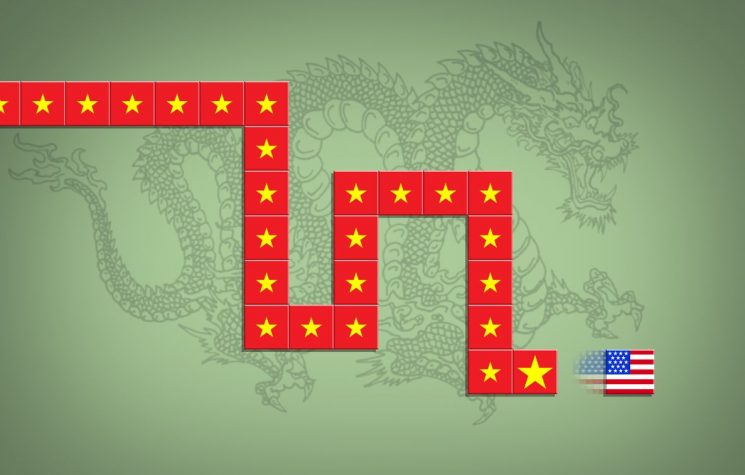

The so-called “strategic gradualism” allows China to advance its fundamental interests without taking a single, decisive action that could provoke direct conflict.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

A strategic profile with a political heart

In the frenetic development of “warfare,” there are some countries that are rapidly moving toward a redefinition of all domains, at least as we have considered them to date. Among these, China occupies a prominent role because it represents the greatest economic and technological adversary for the collective West.

China has adopted a multi-level strategy in the so-called gray space, resorting to practices that include maritime aggression linked to territorial disputes in the South China Sea, cyber operations, forms of economic coercion, and online propaganda campaigns aimed at influencing public opinion. Specialized literature highlights how Beijing exploits ambiguity and employs unconventional tactics, thus complicating the responses of the United States and its allies. Let us therefore take a look at China’s objectives in the gray zone, its strategy and its tools, until we arrive at a logical model constructed to synthesize these elements.

To understand the People’s Republic’s goals in gray zone operations, we must first consider how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) interprets this concept as a political and ideological structure that drives all action. While employing peacetime actions below the threshold of war as an integral part of national policy, Beijing does not define itself as a gray zone actor. Instead, the Chinese leadership recognizes this category as a practice historically used by the great powers—the United States, Russia, and the Soviet Union—including against China itself.

The CCP prefers to avoid Western terminology, speaking instead of “military operations other than war” (MOOTW). Although there is overlap with the American definition of gray zone activities, Beijing does not consider such actions to be hostile acts, but rather strategic tools that serve its political agenda. The different conceptions of peace and conflict between the West and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) explain this choice: in Chinese strategic thinking, “peace” does not equate to the absence of conflict or violence.

China’s central objective remains the assertion and protection of its territorial claims. Since 1949, the CCP has contested sovereignty over lands and seas stretching from the Himalayas to the islands of the East and South China Seas. The 2019 Defense White Paper reiterates the fundamental goal of safeguarding the country’s sovereignty, security, and development interests, including the Diaoyu Dao islands (known in the West as the Senkaku Islands) and other disputed islands.

Over the past two decades, Beijing has intensified the frequency and scope of its actions against rival claims, using both military and non-military means. Through the gray zone, it seeks to consolidate territorial control and push foreign governments and civilian actors to accept its claims. At the same time, Chinese media and officials portray contenders, such as the Philippines, as responsible for violations of international law and threats to regional stability.

For Xi Jinping, these actions are part of the mission of “national rejuvenation,” linked both to the appeal of imperial China and to redemption from the “century of humiliation” marked by colonial occupation and the Opium Wars. In this perspective, MOOTWs are political, economic, social, and strategic tools for transforming China into a fully developed power by 2049.

Regional actions

Operations in the gray space are effective because they exploit the regulatory and cultural ambiguities of the U.S. allies, avoiding both military escalation and the costs of open conflict. Examples such as the differences between Washington and Tokyo on the definition of “armed attack” in incidents between Chinese fishing boats and the Japanese Coast Guard show how Beijing manages to gain advantages while remaining below the threshold of war.

China’s gray zone objectives cover the entire DIMEFIL spectrum, with a particular focus on economic resources. The disputes over the Senkaku Islands, which intensified after the discovery of oil reserves in the 1960s, and the protection of oil platforms such as Haiyang Shiyou 981 in 2014 are examples of this. Similarly, China restricts the mining activities of neighboring countries by invoking the “nine-dash line,” which is not recognized by international law, and accusing them of violations of Chinese sovereignty.

Through such actions, the Chinese government exerts economic pressure and consolidates its presence in disputed territories. The use of coercive force helps to reduce the economic development capacity of its neighbors and strengthen Chinese claims through effective occupation.

China’s assertiveness also aims to strengthen maritime security and deter the projection of U.S. naval power. Control of the South China Sea would guarantee the PLA access to strategic points and maritime corridors, reducing the adversary’s ability to penetrate East Asia in the event of conflict.

The construction and militarization of artificial islands allow China to extend its projection beyond its coastline and prepare the future theater of conflict under more favorable conditions. Constant operations also provide real-world experience to the armed forces, increasing combat capabilities and knowledge of operational areas, as demonstrated by missions with unmanned underwater vehicles or intrusions by research vessels into the exclusive economic zones of neighboring countries.

The increasingly close cooperation between the Chinese Coast Guard, navy, maritime militia, and civilian operators, supported by intelligence fusion centers, enables effective coordination and strengthens China’s position in the gray space. By preparing the ground in peacetime, Beijing aims to secure decisive advantages in the event of future conflict.

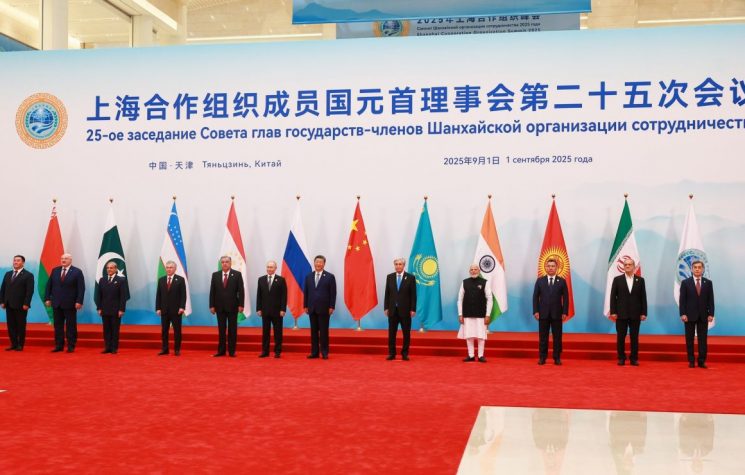

China’s gray zone strategy adopts a “whole-of-nation” approach, involving the entire nation, to achieve the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) central goal of national rejuvenation, along with other strategic objectives. In the Chinese conception, comprehensive national power (综合国力) represents a synthesis of all available resources—diplomatic, economic, cultural, legal, and military. Underlying this idea is the principle that national security is a fundamental duty for every Chinese citizen. The CCP aims to mobilize the population and, consequently, to integrate all sectors of society—from the military to the economic sphere—into a single common struggle. Central to this process is the strategy of military-civil fusion (军民融合), which promotes the use of civilian resources for military purposes and, conversely, the use of military technologies in the civilian sphere, both in times of war and peace.

This logic is also enshrined in the National Defense Law of the People’s Republic of China: Articles 7 and 56 define it as the “sacred duty” of every citizen to defend the country and resist aggression, supporting the development of national defense even in “military operations other than war.” This “omnidomain” and “omnisocietal” approach allows China to coordinate resources and tools in a unified course of action aimed at pursuing national rebirth. To put this vision into practice, Beijing uses a layered strategy, employing different tactics simultaneously or sequentially in different domains, with the aim of achieving its strategic goals while making the response of the United States and its allies more complex and costly.

The Three Wars Strategy

One of the pillars of this approach is the so-called Three Wars Strategy (三种战法), which combines psychological warfare, legal warfare, and media warfare to exert pressure on adversaries. China projects its coercive power through four main mechanisms: geopolitical, economic, military, and cyber/information. Of the twenty gray space tactics considered most problematic, ten are military in nature, four are economic, three are geopolitical, and three are related to the cyber or information domain.

This is a strategic concept developed by the People’s Republic of China in the early 2000s and formalized by the Central Military Commission in 2003. It represents a set of non-kinetic instruments to gain strategic and operational advantages without necessarily resorting to direct armed conflict. The basic idea is that modern warfare is not fought solely with conventional military means, but above all with the ability to influence the perception, behavior, and legitimacy of adversaries.

The Three Wars are divided into three main dimensions:

a) Psychological warfare (心理战, xīnlǐ zhàn)

- Aims to demoralize adversaries and strengthen the spirit of one’s own forces and population.

- It uses propaganda, implicit or explicit threats, demonstrations of force, and psychological operations to influence the enemy’s morale and political or military decisions.

- Examples: military maneuvers in disputed areas, aggressive official statements, diplomatic pressure, or intimidation campaigns.

b) Public opinion warfare (舆论战, yúlùn zhàn)

- Its goal is to control and shape the internal and external narrative, influencing both the Chinese population and international public opinion.

- It uses traditional media, social networks, think tanks, and communication platforms to present China as legitimate and defensive, and its adversaries as aggressive or illegitimate.

- It is a form of cognitive warfare, which aims to gain consensus and diplomatically isolate opponents.

c) Legal warfare (法律战, fǎlǜ zhàn)

- It focuses on the use of national and international law to legitimize its own actions and delegitimize those of others.

- It includes the adoption of domestic laws that reinforce territorial claims, the selective interpretation of international law, and pressure on multilateral legal bodies.

- A typical example is the claim to the South China Sea through the “nine-dash line,” supported by Chinese domestic laws that are not recognized internationally.

Although attention is often focused on military operations—such as the dispatch of Chinese Navy ships into other countries’ EEZs—such actions are not isolated. Political leaders must also address the economic and diplomatic dimensions of China’s activities, which accompany its military ones.

A distinctive feature of China’s gray zone strategy is the slow and gradual pace at which actions are carried out. These tactics, often referred to as ‘erosion’ or ‘salami tactics’, aim to test the willingness of adversaries to respond without openly crossing the threshold of escalation. Each failure to react consolidates a precedent that encourages further Chinese moves and progressively raises the rival’s tolerance threshold.

This so-called “strategic gradualism” thus allows China to advance its fundamental interests without taking a single, decisive action that could provoke direct conflict. By spreading risks and pressures over time, Beijing reduces the likelihood of an immediate and drastic reaction from the affected states, thus managing to slowly change the status quo to its advantage.