In the US, everyone hates Mexicans because they are immigrants “from the south”. Who knows what the indigenous peoples, the original inhabitants of the land invaded by European immigrants, would have to say?

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Everything comes back around, the wheel turns

Premise: The United States of America was founded on the colonization of a land that belonged to peoples exterminated by English criminals who had been released from overcrowded prisons, put on boats and sent adrift towards the West. Forget the romantic tales of the “Pilgrim Fathers”. There was no sanctuary to visit with devotion, no cross to kiss, no saint to be blessed by. There were peoples with a thousand-year history who were exterminated in bloody wars, and the few survivors were locked up in reservations, as if they were animals. All this was done with the help of the European empires, which at the time had embarked on the colonization of the lands of Abya Yala, the pre-Columbian name according to the northerners, or Anahuac or Tawantinsuyu according to the Aztecs and Incas in the south.

The “Americans”, as we have learned to call them, attributing to them an adjective coined by a Florentine navigator who became a naturalized Spaniard, have been the instigators of wars of invasion and colonization throughout the world, exporting the model with which they conquered one of the largest continents on the planet.

Those who inflict invasion, war and genocide will, sooner or later, perish by invasion, war and genocide.

In the beginning was Mexico

Having made this necessary introduction, let us try to understand how things were before the arrival of white European foreigners.

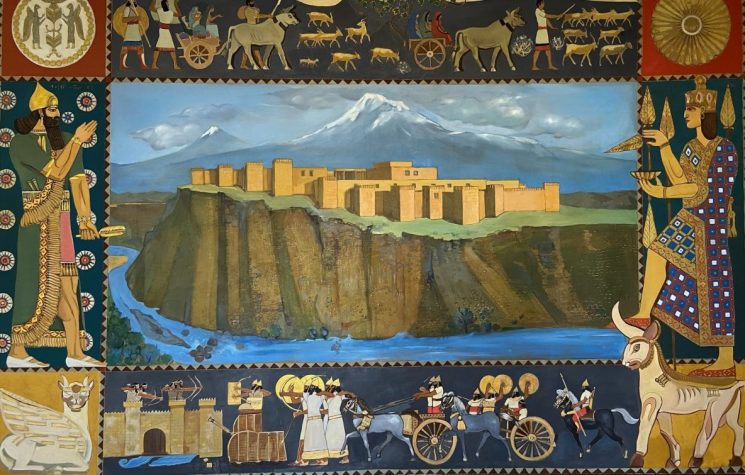

Before the arrival of Europeans, the territory of present-day California was inhabited by an extraordinary variety of indigenous peoples, with one of the highest concentrations of ethnolinguistic groups on the North American continent. Among the main ones were the Chumash, Tongva, Ohlone, Miwok, Yokuts, Maidu, Pomo, Hupa and Yurok. These societies were predominantly semi-nomadic, based on a complex subsistence economy that included hunting, gathering and fishing, with particular importance attached to the gathering of acorns, a central element of their diet.

Culturally and spiritually, the native societies of California had elaborate mythological systems, deeply rooted ceremonial rituals, and sophisticated artistic techniques, including basket weaving, wood carving, and rock painting.

Then came the Portuguese explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, in the service of the Spanish Crown, who explored the southern coast in 1542, paving the way for systematic colonisation that began in the 18th century, particularly from 1769 with the expedition of Gaspar de Portola and the missionary work of Friar Juniper Serra, the Franciscan who took charge of the lands stretching across what is now the area between the cities of San Diego and San Francisco.

Politically, California was integrated into the Viceroyalty of New Spain, with its own province.

With Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821, California came under the control of the new Mexican state.

The religious missions were secularized, church property was confiscated and redistributed, giving rise to the landowning aristocracy of the Californios. Mexican control was weak, especially in the northern regions, where the influence and presence of Anglo-American merchants, explorers and settlers grew, heralding the transition that was to follow.

The first US conquest

Between 1846 and 1848, US forces occupied Mexican California. The war had deep roots in the US expansionist doctrine known as Manifest Destiny, according to which the extension of Anglo-Saxon and Protestant civilization from the Pacific to the Atlantic was considered legitimate — and even providential.

The conflict broke out in the aftermath of Texas’ annexation to the United States in 1845. Texas had declared independence from Mexico in 1836 after a separatist war and had remained an autonomous republic for almost a decade. Mexico had never recognised Texas’ independence, let alone its annexation by the United States, considering it a hostile act.

The casus belli was the dispute over the southern border of Texas: the United States claimed that it was the Rio Grande, while Mexico considered the Nueces River, further north, to be the border. US President James Polk, a staunch supporter of territorial expansion, sent troops under the command of General Zachary Taylor into the disputed territory. The attack by Mexican troops on American patrols in 1846 provided Polk with the pretext to declare war, claiming that American blood had been shed on “American soil”.

On the northern front, in Texas, General Taylor won important victories, such as at Monterrey and Buena Vista. In 1846, the Bear Flag Revolt broke out in California, in which US settlers proclaimed the Republic of California, which then joined forces with the Americans and quickly occupied the entire region. The Americans marched to Mexico City in September 1847, forcing the government to sign a peace treaty.

This was the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on 2 February 1848. Under the terms of the treaty, Mexico ceded 55% of its pre-war territory to the United States, including the present-day states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada and Utah, as well as parts of Colorado and Wyoming, and the border between Texas and Mexico was definitively established along the Rio Grande. All this for $15 million from the United States, which undertook to compensate American citizens with claims against the Mexican government.

Many Mexicans living in the ceded territories quickly became a minority, forced to flee because of discrimination and cultural and legal differences. The ethnically indigenous populations were reduced to a minimum, with some becoming extinct.

In 1850, the new state of California was admitted to the Union as the 31st state of the United States, without going through territorial status, a rare occurrence in American history.

An unresolved political problem

After the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), the new south-western frontier remained porous. Mexican workers moved freely, mainly in agriculture, mining and railway construction. There were still no specific federal laws regulating immigration from Mexico.

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act ushered in an era of selective and racialized immigration policies, but it did not affect Mexicans, who became an alternative source of labour.

However, it was in 1907 that the first federal measures began to distinguish between “desirable” and “undesirable” immigrants, but Mexican labour continued to be encouraged informally.

Between 1910 and 1930, there was the first major wave of migration: the Mexican Revolution and the First World War drove tens of thousands of Mexicans to seek refuge or work in the United States. US agricultural and industrial needs encouraged their entry. This led to the creation of the Border Patrol, a border police force which, with the Immigration Act of 1924, mainly targeted Europeans and Asians, institutionalizing the border with Mexico. From 1929 to 1935, during the Great Depression, nearly one million Mexicans, including US citizens of Mexican origin, were repatriated or forcibly deported, an event that went down in history as the Mexican Repatriation.

This led to the creation of the Bracero Programme in 1942, a bilateral agreement allowing millions of Mexican agricultural workers to enter the United States legally and temporarily. This move enabled the US to meet its labour needs for the Second World War. With Operation Wetback in 1954, another massive deportation campaign was launched, once again involving around 1 million people. Eisenhower was in power at the time. Curiously, the Bracero Programme remained in place until 1964, when it was dismantled due to union pressure over the exploitation of workers.

In 1965, the Immigration and Nationality Act (also known as the Hart-Celler Act) was passed, abolishing the national quota system but not providing for a sufficient number of visas for Latin American immigration, and opening a period of uncontrolled Mexican immigration that would grow steadily until the 1980s.

With the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 signed by Reagan, approximately 2.7 million illegal immigrants were regularized and labour was regulated. In 1990, another Immigration Act expanded visas, but it was with NAFTA in 1994 that, by opening the trade corridor between the US and Mexico, the situation paradoxically worsened: new waves of illegal immigration, economic displacement, and restrictions on freedom. In 1996, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act established very harsh penalties for illegal immigration, speeded up repatriation and criminalized migration.

Thus, in 2001, after 9/11, the Department of Homeland Security was created to deal with border controls, thanks in part to the lengthy border barrier provided for by the Secure Fence Act of 2006 and strengthened in 2012 under the Obama administration with the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, dedicated to the immigration of children.

Under Trump and Biden, the Zero Tolerance Policy has gained ground, along with a so-called “Remain in Mexico” directive under the Migrant Migration Protocols, which forces asylum seekers to remain in Mexico while awaiting a decision.

So, in all these years, what has changed?

The United States of America, yesterday as today, has a strong economic dependence on Mexican labour, especially in agriculture, construction and logistics. The repression of immigration has never stopped, demonstrating that the problem is not just a matter of migration, but a historical, cultural and political wound that has never been healed, namely that of a colonization that tore apart a social system that was historically rooted in that geographical area.

It’s time for revolt, but who stands to gain?

Los Angeles is the symbol of the West Coast, the place par excellence of the “American dream”, home to Hollywood, the icon of American icons, the factory of propaganda and American identity.

What is happening there right now is therefore extremely powerful. Let’s not forget that at the beginning of January, there was an iconic fire in Hollywood, with the famous giant sign in flames.

The unrest in the United States between protesters opposed to ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) and law enforcement deployed by the Trump administration seems to be a possible prelude to what some observers have long feared as a “second American civil war”.

Whether this dynamic will evolve into a real civil conflict or peter out into a period of tension remains to be seen, but it is essential to grasp its profound symbolic and political significance. This is not simply a protest against restrictive immigration policies. The ideological visions clashing in the United States today echo that turbulent past we have described.

Today, the expansion of industrial urbanism – which has transformed into a globalized financial economy – is undergoing a profound crisis. The free movement of labour, which once defined the American identity, now appears to be a source of tension rather than a source of benefits. In this context, the ideological fronts of the old civil war seem to be re-emerging, albeit with renewed meanings and alignments.

The new fault line no longer coincides with the North-South geographical dichotomy, but manifests itself between the large, cosmopolitan and globalized metropolises, which are predominantly democratic, and the rural or peri-urban areas, which are seeking economic security and a reaffirmation of identity, often oriented towards the Republican Party.

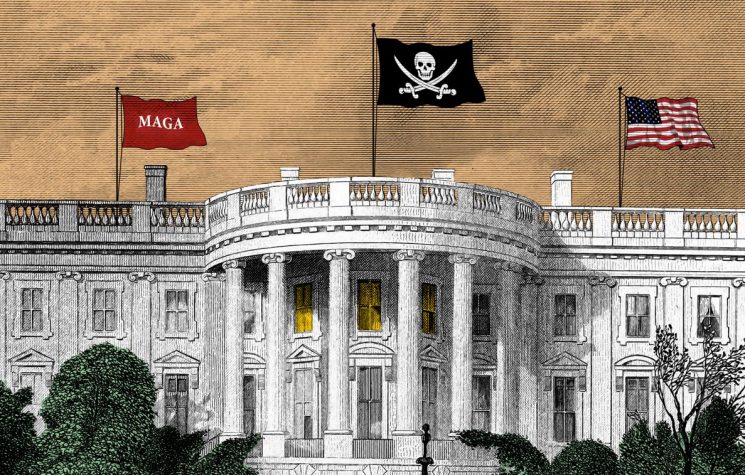

This polarization is also evident at the institutional level. Democratic authorities, such as the mayor of Los Angeles and the governor of California, are adopting a language of radical opposition – speaking of “democracy versus tyranny” – and openly delegitimizing the choices of the federal executive. For his part, President Trump is turning the accusations around, accusing local authorities of subversion and incitement to revolt.

This divide is spreading to many US urban centres – such as Seattle, Chicago and Philadelphia – where Democratic administrations are fuelling the narrative of an existential conflict between incompatible models of civilization. And this is a crucial point.

However, it is difficult to imagine that political leaders with solid institutional careers would be willing to go as far as direct confrontation if the Insurrection Act were activated. This law gives the president extraordinary powers to use the army and the National Guard as instruments of internal order.

The fact remains, however, that once the collective imagination has been mobilized around an epochal and non-negotiable clash between irreconcilable visions of society, it could become difficult to bring dissent back within the confines of ordinary institutional confrontation.

If such events were to occur in another country, many media outlets would speak of a “colour revolution” against an authoritarian government, in favour of freedom and rights. But compared to the scenarios of colour revolutions promoted elsewhere, the United States lacks one crucial element: support from the United States itself.

The situation is ongoing, and we will therefore follow developments.

Now let us ask ourselves: who benefits from all this?

Let’s take a moment to look at the chessboard.

California is a stronghold of liberalism, a coastal area, the inner Rimland of the US. California Governor News is a staunch Democrat, as is Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, both enemies of Trump. It is curious that in the general chaos, the champions of George Soros have come to the aid of the rioters.

In the US political system, each state has quite broad powers. The federal government cannot send troops without the governor’s consent, but News refuses to do so, so Trump sends in troops, breaking the law, and is immediately attacked by the courts. It is also worth noting that the Democratic fringe in California is opposing Trump’s actions in every way possible, which could bring the country to the brink of civil war. There are currently 4,800 soldiers in Los Angeles, including the National Guard and the Navy, almost twice as many as were sent to Iraq and three times as many as in Syria.

Meanwhile, Xi Jinping, during a meeting with Mexico’s left-wing president Claudia Sheinbaum, expressed concern about the human rights situation in Los Angeles. Another interesting fact: the Mexican president’s grandfather was called Chone Juan Sheinbaum Abramivitz, who emigrated from Lithuania in 1928 and became both a jewelry merchant and a member of the Mexican Communist Party. That’s right: a luxury merchant and a communist at the same time. A dichotomy that should give us pause for thought.

In a sense, therefore, Los Angeles is in the midst of a Trumpism crash test, i.e. an opportunity for Trump to:

- Affirm his ideological vision of “America”

- Use force and urgency to change immigration policy, dealing a severe blow to Mexican immigration

- Oust many political enemies from the Californian administration

- Bring to the fore the hawks, traitors and enemies who have been working behind the scenes

- Take control of Silicon Valley and Hollywood

It is clear that the current situation is very, very tempting. If this is a false flag, we will probably find out soon. It would not be surprising, as American presidents have come up with much worse things against their own people in order to get what they wanted.

What we do know is that this detonator may have been activated for one purpose, but it could also lead to another. The US is on the brink of an internal crisis that has been brewing for years and will lead to civil war. The collapse of the Hegemon is irreversible, whether the Republicans or the Democrats are in power.

We are now witnessing a historic transition that will leave a mark on the memory of those lands. After centuries of violence and unresolved problems, the wound has become infected and is now causing the system to rot.

Because if we want to focus on the short-term political problem, i.e. the feud between Trump and his opponents, we must not forget to consider the long-term problem, which is more important: who does California belong to?

California was founded on the pueblos. The most important rivers are called Sacramento and San Joaquin. The largest mountain range is the Sierra Nevada. The main cities have Spanish names, such as Los Angeles, San Diego, San José, San Francisco, with Sacramento as the capital.

In the US, everyone hates Mexicans because they are immigrants “from the south”. Who knows what the indigenous peoples, the original inhabitants of the land invaded by European immigrants, would have to say? No one ever asks.

California is Mexico! Yankees go home!