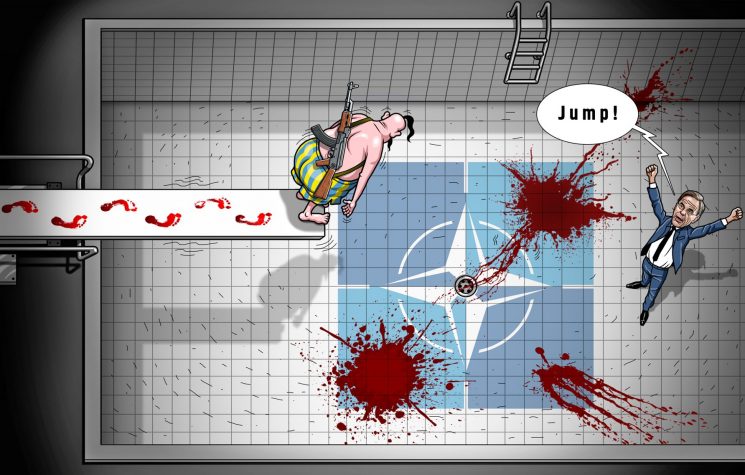

A US draw‑down would leave a large “defence gap” for NATO’s European members.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The London‑based International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) has published a report entitled “Defending Europe Without the United States: Costs and Consequences.”

Founded in 1958, the IISS examines global security, defence and geopolitical issues, and its reports are frequently cited by NATO, the United Nations and national defence ministries.

Authored by Ben Barry, Douglas Barrie, Henry Boyd, Nick Childs, Michael Gjerstad, James Hackett, Fenella McGerty, Ben Schreer and Tom Waldwyn, the report concludes that if the United States withdrew from NATO, European countries would need to allocate USD 1 trillion to defence over the next 25 years.

That would mean raising defence spending to 3 percent of GDP.

According to the scenario, roughly 50 percent of total expenditure would go to procuring military equipment (tanks, armoured vehicles, aircraft, ships, missiles, UAVs, etc.); 25 percent to developing intelligence assets, space forces and command‑and‑control systems; 20 percent to equipping, training and logistically supporting personnel; and 15 percent to investments in the defence industry and purchases from abroad.

These hefty sums are based on a scenario in which all 128,000 US troops and their equipment are fully withdrawn from Europe by 2027.

What’s in the report?

The 32‑page report divides the threats Europe faces into two main headings.

The first points to Russia’s military power, noting:

“Russia’s economy is on a war footing and its defence industry is running at full capacity. Even if the fighting in Ukraine stops, Russia could rebuild its forces against NATO‑Europe.”

The second major problem is the shifting focus of the United States:

“Europe can no longer rely on automatic US support. Former President Donald Trump’s rhetoric on NATO and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth’s 2025 remark that ‘Europe must now shoulder its own defence’ show that Washington’s attention has pivoted to the Pacific. European allies therefore must build capabilities that can deter Russian aggression without US backing.”

The core assumption

The report assumes a mid‑2025 cease‑fire in Ukraine, after which the US begins to withdraw from NATO and pull troops out of Europe.

Its calculations cover how quickly Russia could again pose a threat after a cease‑fire, the scale of current US contributions to NATO, Europe’s force readiness, equipment gaps, costs, timelines and leadership issues.

“The Russian threat to Europe”

In its first section, the report emphasises that Russia remains “the principal military threat to the Euro‑Atlantic region.”

For NATO allies, the key task is to determine how fast Moscow could regenerate its forces once hostilities cease.

Key insights on Russia’s potential threat include:

- UK Chief of the Defence Staff Admiral Tony Radakin says it may take President Vladimir Putin five years to rebuild the Russian army to its February 2022 level, and another five years to remedy weaknesses exposed by the war.

- Estonia’s Foreign Intelligence Service warns that within a decade, a “Soviet‑style mass army,” though technologically behind, could seriously threaten NATO.

- Norwegian Chief of Defence General Eirik Kristoffersen believes the alliance has only two to three years to prepare.

- Danish Defence Intelligence assesses that Russia could stage local border clashes six months after a cease‑fire, a regional war in the Baltic within two years, and a large‑scale European assault within five years.

The IISS authors lean toward Denmark’s forecast, adding:

“Despite difficulties, Russia could present a serious military challenge to NATO allies as early as 2027, particularly for the Baltic states. By then, its ground forces may approach their February 2022 strength while the air force and navy—which suffered far less—remain largely intact. Russia’s rapid regeneration capacity should not be underestimated; its economy and industry have fully shifted to a war footing and Moscow has sourced military hardware from abroad.”

Cease‑fire: “Breathing space for Russia, countdown for Europe”

Detailed figures in the report show Russia’s defence spending rose 41.9 percent in real terms from 2023 to 2024, reaching 13.1 trillion roubles (about USD 145.9 billion, or USD 462 billion in PPP terms). Defence now equals 6.7 percent of GDP, more than double the pre‑war average, and is projected to climb to 7.5 percent in 2025.

Will Moscow cut spending after a cease‑fire? Europe doubts it:

“The Kremlin has neither abandoned its strategic goals in Ukraine nor ceased efforts to destabilise Europe, so assuming defence outlays remain high is prudent.”

Europe worries that any cease‑fire will give Russia a breather while starting a countdown for Europe:

“Although Russia’s ground forces have suffered heavy losses, its quickly recoverable air and naval capabilities will keep Europe’s defence posture on permanent alert.”

NATO’s “big war” plan for Europe

The second part of the report focuses on SACEUR (Supreme Allied Commander Europe), NATO’s top military command—always held by a four‑star American general or admiral.

The report recalls that NATO military staff, responding to SACEUR’s needs, have deemed the total force required to execute defence plans 30–50 percent larger than before 2022.

Although the alliance is set to approve new goals at its June 2025 ministerial meeting, Allied Command Transformation head Admiral Pierre Vandier has highlighted a glaring gap: current pledges already lag 30 percent behind previous targets—and the new ones call for another 30 percent increase.

No official data specify the scale of any US contribution in a full‑scale European war with Russia. Yet IISS analysts note that NATO heavily relies on US strategic intelligence, space, cyber assets and its vast nuclear arsenal:

“In conventional operations to counter Russian aggression in Europe, probable US support would amount to roughly 128,000 personnel plus combined land, sea and air units.”

What if the US pulls out of NATO and Europe?

The report’s third section explores the consequences of a US withdrawal.

Assuming this drastic—though time‑consuming—scenario, IISS simulations outline:

- US bases, training ranges and other infrastructure could be sold to host nations or commercial buyers; surplus munitions and spares might be handed over to European armies.

- Europe would have to replace US‑provided training facilities, teams and equipment on its own.

- Reduced US intelligence sharing would expose gaps in Europe’s space and all‑domain ISR assets, seriously hampering early warning and plans to counter a Russian attack.

The price tag

If Europe had to duplicate existing US capabilities, the one‑time procurement bill plus 25‑year life‑cycle costs would reach about USD 1 trillion—and that figure excludes intelligence, space, cyber and nuclear forces.

Annual costs to match US contributions lie between USD 226 billion and 344 billion.

“Even if the money is found, capacity is lacking”

The authors stress that even if Europe could foot the bill, its industrial capacity is insufficient:

“European defence firms are adding assembly lines and pursuing mergers and acquisitions, but progress is uneven and major obstacles remain.

If allies want extra aircraft carriers or nuclear‑powered attack submarines, delivering them will be a huge challenge.

Meeting short‑term demand for armoured vehicles outstrips current output. States must inject major investment, convert plants from other sectors, and sign deals with long‑time suppliers such as Canada and the US—or with non‑European producers.”

Since procurement is often done nationally, order volumes are small compared with US purchases. The report recommends multinational cooperation to place larger orders.

Conclusions and recommendations

The central message is clear: a US draw‑down would leave a large “defence gap” for NATO’s European members. Coupled with the possibility that Russia could rebuild its ground forces by 2027 after a cease‑fire, Europe hears alarm bells.

Even raising Europe’s defence industry to a Russian‑style “war economy” won’t suffice. The obstacles—workforce, production lines, supply chains and finance—are immense. For example, ordering just 400 extra combat aircraft is a massive undertaking given global manufacturing capacity.

To escape this bleak scenario, Europe must:

- Boost defence spending beyond current plans.

- Make joint multinational procurements to spread costs.

- Deploy public spending and convince citizens of the need.

- Take bold financial‑industrial steps, mixing public and private investment, prioritising outlays and accepting higher risk.

Yet money and hardware are not the hardest part—the toughest challenge is political unity and common will.

Europe already faces migration, climate and economic crises. Even current levels of aid to Ukraine have sparked widespread social unrest. The much‑feared rise of the far right—fuelled by demands for stability and security—has begun toppling governments.

In such a political climate, if the US leaves, and “more militarisation” becomes the only answer, Europe may face prolonged political upheaval across the continent.