The impact of Bergoglio’s papacy can be viewed on two levels, Stephen Karganovic writes.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

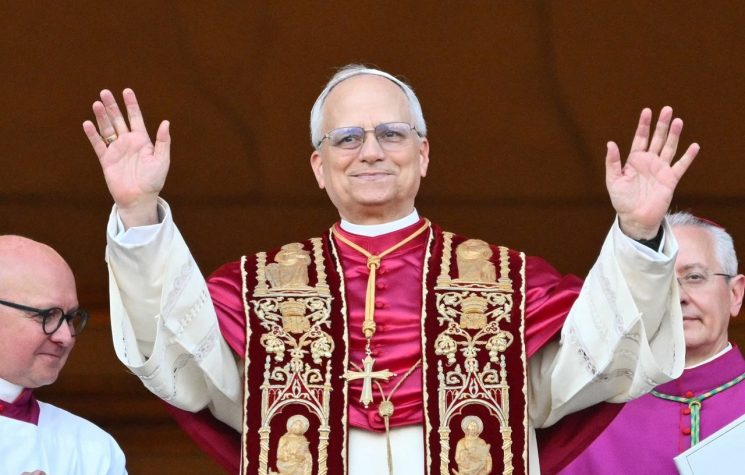

The departure of the Roman Pontifex Maximus will lead to a re-examination of his legacy and, more broadly, intense speculation about the reversibility of Roman Catholic communion’s further decline, which was accelerated during his reign. Will the College of Cardinals, eighty percent of whom consist of Bergoglio’s carefully chosen and ideologically compatible appointees, have the objectivity and moral courage to select from their ranks as his successor anyone, if such there be, who is not a doctrinal replica of the man to whom they owed their berettas?

The path to the enthronement of Bergoglio is now, in retrospect, plain to see. The purpose of his elevation was to put finishing touches to the protracted process of decomposition of the Vatican and of that part of the Western world which historically drew from it its spiritual and cultural sustenance. The project to complete the induced collapse of the Western church as a recognisably Christian institution has been nurtured for far too long and has been executed with extreme discipline and precision. With success within grasp, the consummation of the intramural plot of Ciceronian fiendishness and complexity cannot be left to the vagaries of chance.

And so it won’t be if we can take seriously, as we should, Russian historian Olga Nikolaevna Chetverikova’s meticulous exposition of the process of hostile infiltration of the Roman Catholic church which goes back for at least a century and a half and long precedes its most visible recent manifestation, the Second Vatican Council. The chief goal and purpose of that nefarious process was to capture the grand institution from within, to obliterate the remnants of doctrinal truth and cohesion it had still managed to preserve for nearly a millennium after the Schism and to morally disorient and debilitate the vast civilisation that had grown around it.

The impact of Bergoglio’s papacy can be viewed on two levels. One is the manner in which it fits into the general movement to restructure the Roman Catholic church since at least the Second Vatican Council, when that process was launched publicly and visibly, although Chetverikova amply documents in her book that, discretely, it had actually started considerably before. The second level concerns the personal stamp which Bergoglio put on his papacy, a subject that is no less interesting.

The aggornamento announced by Pope John XXIII, which as even many committed Catholics argue, found its destructive expression in the Conciliar dispositions, was perfected in the wide departures from the core elements of traditional Christianity which were unabashedly implemented during Bergoglio’s reign. Up to Bergoglio’s installation in the Papacy the doctrinal and liturgical transformation of the Roman Catholic church followed a zig-zag path, always having to take into account the sentiments of traditional Catholics and stopping short of of plunging into excessive modernism, for appearances’ sake at least. With the arrival of Bergoglio such restraints were notably dropped.

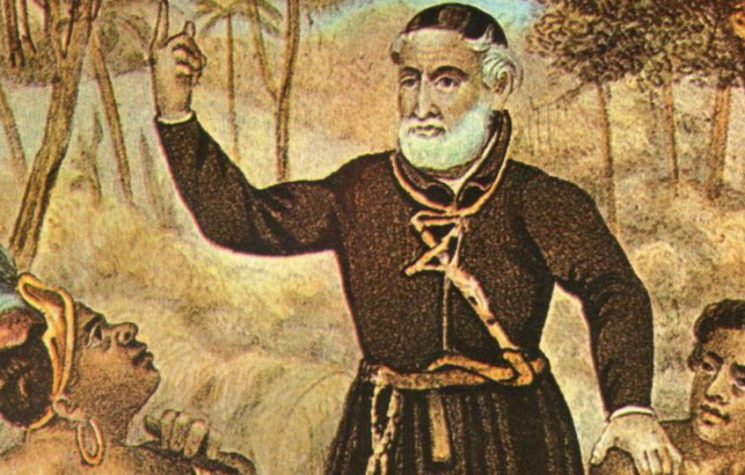

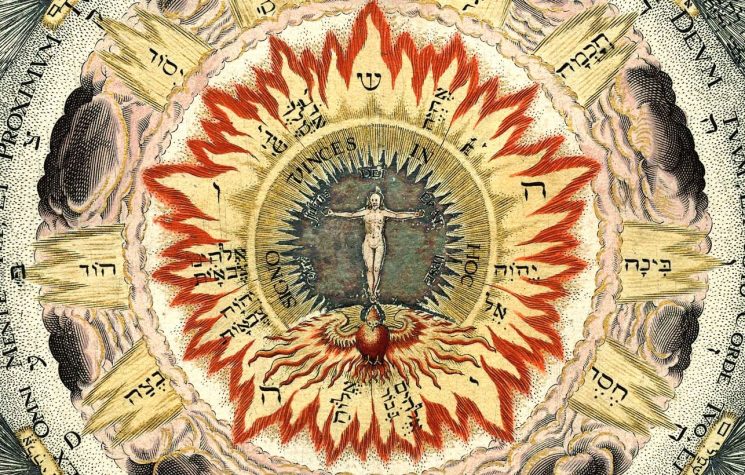

What in earlier pontificates was being done gingerly, testing the waters, as when in 1986 the Vatican organised the spiritual Babylon known as the interfaith gathering for world peace in the basilica of St. Francis in Assisi, under Bergoglio was imposed and promulgated urbi et orbi in the form of the blasphemous affirmation that all religions constitute valid paths to God, a notion equally abhorrent to traditional Catholicism and to the perennial teaching of the Christian faith. That notion, to the consternation of many Catholics, not to speak of other Christian believers, was proclaimed at the Amazonian synod in the Vatican in 2019 with the introduction of the indigenous pagan deity Pachamama as a legitimate object of quasi-adoration, in the presence of the highest authorities of the Roman Catholic church and Pontifex Bergoglio himself.

Bergoglio was insistently harping on this key syncretistic theme up to a week before his demise. In his address to Catholics and followers of other religions in Singapore he dismissed the exclusive claims of his own faith, boldly asserting instead that “religions are seen as paths trying to reach God… they are like different languages that express the divine … like languages that try to express ways to approach God. Some Sikh, some Muslim, some Hindu, some Christian.”

The equalisation of all religions and denial of primacy to any of them expresses in a nutshell the doctrine and spirit of the New Catholicism which has been unfolding gradually during the Post Conciliar decades, of which Bergoglio was an insistent articulator and most conspicuous porte-parole.

The Bergoglian “church” is designed to be stripped of its distinctive characteristics and watered down to the point where it can comfortably be merged with the secular milieu surrounding it. It is an emerging system in which the Pontifex, Bergoglio or his successor, shall be content to be demoted from infallible Vicar to manager of the system’s religious desk, in return for a seat and a few crumbs from the globalist table.

The role of all creeds in such a world reordered in accordance with principles not yet fully disclosed, but which may be anxiously suspected, is to become the spiritual indoctrination department for the elitist masters and a pacifier for the helot masses, enabling them to endure the rigours of their slavery.

On the personal level, the Bergoglian legacy is no less problematic. It is epitomised best perhaps by his platitudinous encyclical Fratelli tutti, which upon its author’s passing, and to the rightful consternation of traditionalist Catholics, was singled out for effusive praise precisely by the most sinister of the secret societies, whose principles had obviously inspired the encyclical’s thoroughly secular concerns and rhetoric.

It would seem that much of what passed for the public persona of Bergoglio, the carefully cultivated image of a humble and approachable servant of the Almighty, was no more than a veneer. His vindictive treatment of Archbishop Vigano, the most relentless critic of his pontificate, bears that out. Not a shred of fraternal love or patience were demonstrated to soften the persecution of the gadfly Archbishop whose incessant missives deconstructing the errors of Bergoglio’s reign must have rankled unbearably. On the other hand, the kind-hearted patience and tolerance Bergoglio showed for the perversities of Cardinal MacCarrick and other malefactors in the highest echelons of the Vatican was in striking and shameful contrast to the shabby treatment he meted out to his righteous brother, Archbishop Vigano.

Nor, as Larry Johnson points out, had there ever been a hint on Bergoglio’s part, beyond pro forma words and even those markedly restrained, of meaningful action in solidarity with the martyred population of Gaza, much less of support for his presumed fratelli in the faith, the persecuted Orthodox Christians of Ukraine.

“Of the dead nothing but good” is a noble injunction but in the present case it is perhaps not suitable for universal and uncritical application. Without intending to be judgmental, in conclusion it must be said that Bergoglio will not be remembered as either a Good Shepherd or as an effective keeper of the doctrines and traditions of his troubled communion.