Parolin emerges as the ideal compromise candidate—well-positioned for the papacy and aligned with the multipolar shift in global geopolitics.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The Catholic world has been in a state of tension and anticipation in recent weeks due to the convalescent condition of Pope Francis, which seemed to worsen day by day, suggesting the inevitability of an imminent succession. However, his health suddenly improved, temporarily pushing aside the pressing question: Who will be the next Pope?

Still, the Pope is 88 years old, and his health remains fragile, as expected. While the urgency of the papal succession has been delayed, the question still looms on the near horizon of the Catholic world.

Now, one might ask: Why does the election of the Pope even matter? Well, in a dialogue about Poland between Stalin and Churchill, the Soviet leader famously quipped, “How many divisions does the Pope have?”—implying that the Pope was irrelevant in geopolitics. With all due respect, we would disagree. On the contrary, it seems to us that the Pope remains a relevant geopolitical actor.

True, we are far from the medieval era, when the Emperor and the Pope served as the defining pillars of Christian civitas, maintaining a degree of stability and peace over kingdoms and nations. But it would be a mistake to completely dismiss the Vatican’s political potential.

First, the Vatican has a “virtual population” of 1.3 billion people—the entirety of the world’s Catholics—who are influenced by the Pope’s words to varying degrees, from absolute adherence to subtle persuasion. No other religion enjoys the same level of centralization as Catholicism, making the Pope, the Patriarch of Rome, the most powerful religious leader in the world.

This means the Papacy naturally wields influence over elections (something every Ibero-American knows well), public policies, and social services. Of course, this influence is usually subtle, at least in modern times. But it is undeniably present.

This reality grants the Vatican considerable diplomatic power. For instance, John Paul II played a key role in accelerating the collapse of communism in Poland. More recently, the Vatican has pursued its own diplomacy aligned with the multipolar transition, including relations with China, rapprochement with the Russian Orthodox Church, outreach to Cuba, and—most importantly—calls for Europe to reclaim a constructive role in international relations, with the Papacy offering to mediate the Ukrainian conflict.

The relevance of the Vatican’s international role is further evidenced by the abdication of Benedict XVI. While speculation on such matters is delicate, there is substantial literature suggesting that Benedict XVI stepped down under overwhelming pressure from the U.S., exhausted from resisting demands to pivot the Vatican away from Russia. His declarations hinted at a potential Vatican-Moscow alliance to counter the nihilism (as Benedict saw it) promoted by the U.S.

Thus, while the Pope may lack armored divisions or nuclear weapons, the Vatican remains one of the world’s greatest centers of soft power, with significant capacity for unconventional, subtle geopolitical operations.

The question of “Who will succeed the Pope?” therefore remains relevant even now.

With that established, we must now consider who could succeed Pope Francis if he passes away in the coming years.

First, it is important to note that a candidate over 80 is highly unlikely to be elected. Cardinals of that age are ineligible to vote, ruling out nearly all candidates from the last conclave—including Guinean Robert Sarah, a favorite among traditionalists and conservatives.

Additionally, the Vatican is fundamentally divided between conservatives and progressives, with a centrist faction trying to maintain balance.

Following this logic, the cardinals ideologically closest to Pope Francis and eligible for election are Italy’s Matteo Zuppi and the Philippines’ Luis Tagle.

Zuppi was elevated to the College of Cardinals by Pope Francis himself and owes all his appointments to him, making him Francis’ likely preferred successor. As president of the Italian Episcopal Conference, Zuppi represents a bloc of cardinals accounting for 20% of the electorate. In practice, he is even more progressive than Francis, strongly advocating for immigration and blessing LGBT couples in the Church. However, his achievements (and thus his reputation among cardinals) are minimal.

Notably, Zuppi is Francis’ special envoy on Ukraine, having visited Volodymyr Zelensky—without extending an equivalent invitation to Vladimir Putin. Despite the Pope’s claims of neutrality, his envoy appears slightly biased toward Ukraine.

Luis Tagle, meanwhile, would be the first Asian Pope and has been called the “Bergoglio of Asia”—a potential advantage, given that Asia (along with Africa) is the future of the Catholic Church. Unlike Zuppi, who lacks major roles, Tagle holds key positions: Pro-Prefect of the Dicastery for Evangelization, President of the Interdicasterial Commission for Consecrated Life, and President of the Catholic Biblical Federation.

He is less progressive than Zuppi, taking a firmer stance against abortion and remaining ambiguous on blessing LGBT couples. However, his relative youth (by papal standards) works against him—at the same age as John Paul II when elected, Tagle could have an excessively long papacy, which would frustrate those tired of Francis’ style or seeking a conservative shift.

On the conservative side, the favorites are Germany’s Gerhard Müller and Hungary’s Peter Erdő.

Müller, a Benedict XVI-era figure and former Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, has a long Vatican career focused on preserving the Church’s historical continuity. Yet his positions are radically opposed to Francis’—on female deacons, LGBT blessings, climate discourse, communion for the divorced, and the China-Vatican agreement. He is also more pro-Ukraine than even Zuppi.

With such polarizing stances—including accusations of heresy against Francis—his chances of securing enough votes are slim.

Hungary’s Peter Erdő is a more palatable conservative alternative. Once one of the youngest cardinals in centuries, Erdő is a key ally of Viktor Orbán and helped restore Christianity in post-atheist Hungary. He favors dialogue with the Russian Orthodox Church and China while criticizing mass immigration and LGBT openness—yet avoids direct confrontation with Francis.

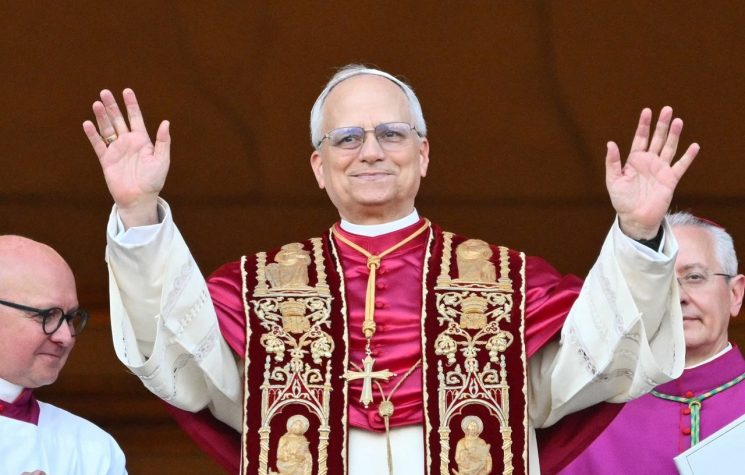

But the strongest candidate to succeed Pope Francis is neither a progressive nor a conservative, but the pillar of Vatican centrism: Cardinal Pietro Parolin.

As Secretary of State since 2013 (effectively the Vatican’s foreign minister), Parolin has an impressive record. He restored ties with Cuba, mediated U.S.-Cuba talks, visited Moscow in 2017 amid Western demonization of Russia, and engineered the Vatican-China deal on bishop appointments—balancing Catholic mission with China’s security demands. He even engaged the Taliban to encourage moderation.

On Russia, he is more neutral than Zuppi or Müller, continuing Benedict XVI’s “Russophile” geopolitics. Meanwhile, he holds moderately conservative stances on moral issues, avoiding polarization.

With many cardinals wanting neither a full continuation of Francis’ legacy nor an overly polarizing conservative, Parolin emerges as the ideal compromise candidate—well-positioned for the papacy and aligned with the multipolar shift in global geopolitics.