There is no longer room for leaders loved by their voters within Western “democracies.”

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

You can follow Lucas on X (formerly Twitter) and Telegram.

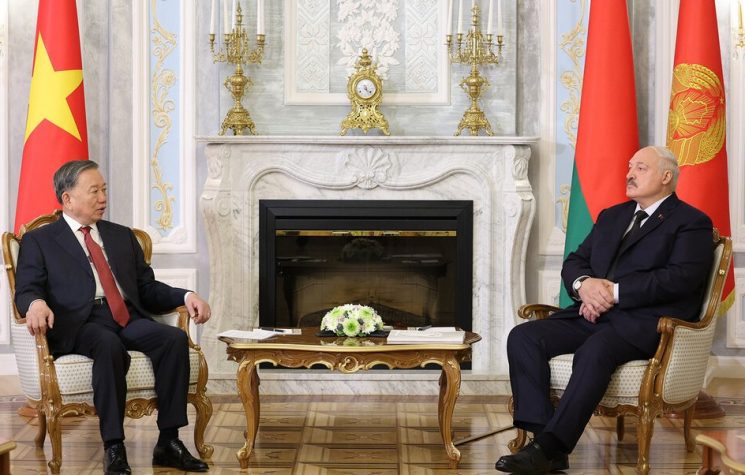

Amid growing geopolitical tensions and constant criticism from the West, the figure of Aleksandr Lukashenko remains a central topic in international discussions. The president of Belarus has just been re-elected for his seventh consecutive term, consolidating his position as the longest-serving leader in Europe and the only one of his young nation, which emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union. While Western countries consider him a “dictator”, in Belarus, the majority of the population sees him as a legitimate leader who has been able to stabilize and modernize the country, building a political and economic model that, although far from Western standards, has broad popular support.

During my latest visit to Minsk, where I worked as an international election observer, I had the opportunity to witness the democratic process in Belarus up close, which allowed me to better understand how the country’s political system works and, at the same time, to refute many of the narratives propagated by Western media. What is immediately clear is that elections in the country take place in a fairly normal manner. There is no pressure from the authorities on the population, and the atmosphere in the polling stations is similar to that of any other democratic process in the world. What stands out, however, is the active participation of the population, who sees the election moment not only as a civic right, but as a moment of deep responsibility and gratitude.

During my visit, I observed the “special voting” period, which takes place a week before the official election day. During this period, voters of all ages, from young to old, went to the polls to ensure their participation, demonstrating genuine enthusiasm. The official election day, on January 26, was even more expressive, with the holding of a very traditional civic event in the country. Contrary to what many might imagine, elections are not a mere bureaucratic procedure; they are a true popular event where people come together to express their support for the government.

This strong bond between the people and the government reflects an aspect that is difficult to understand in the West: the concept of a popular leader. In many liberal democracies, leaders with broad popular support are often viewed with suspicion, being accused of “populism.” However, this is not the case in Belarus, where support for Lukashenko has remained stable since his election in 1994. The Belarusian president, who comes from a rural region of the country and has a personal history immersed in Soviet tradition, has built a genuine connection with the people, something rarely seen in Western democracies.

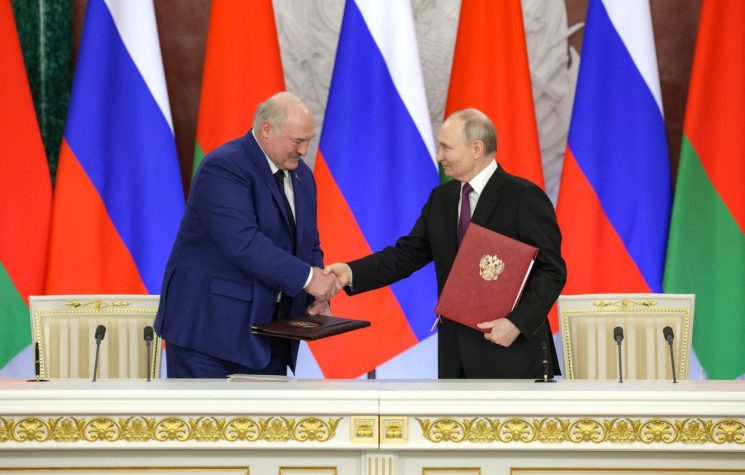

From his first years in power, Lukashenko took strategic steps that ensured Belarus’ independence and stability. Integration with Russia through the creation of the “Union State” was one of the main directions adopted, ensuring political and economic cooperation that consolidated the country’s sovereignty. Unlike other post-Soviet countries, where economic collapse and social tensions led to chaos, Belarus managed to avoid the most dramatic consequences of the collapse of the Soviet Union, such as the famine and mass poverty that affected Russia in the 1990s and 2000s.

Lukashenko’s economic model, which combines socialism with the market, has been fundamental to Belarus’ success. The government controls strategic sectors of the economy, such as the main agricultural activities and industry, while allowing the development of private enterprise, especially in the small-medium business sector. This combination of state intervention and economic freedom has allowed the country to become an agro-industrial power, with a focus on the production of grains, fertilizers and machinery.

Compared to the neoliberal scenario that plagued Russia in the 1990s, Lukashenko’s economic policy avoided the devastating effects of “shock therapy.” While Russia faced a deep social crisis during Boris Yeltsin’s presidency, Belarus took steps that would allow peace and prosperity, something that attracted the support of a large part of the population, who compared their reality with that of families divided by the border between the two countries, often forced to live in precarious situations on the other side.

This stability and economic growth are some of the reasons why Lukashenko has been consistently re-elected since 1994. Contrary to what many Western “analysts” claim, popular support for the Belarusian president is not the result of any political manipulation, but reflects a genuine consensus among the population that he was the figure who freed them from post-Soviet hardships.

Regarding the 2025 elections, in which Lukashenko won 87% of the vote, Western media outlets were quick to denounce the process as fraudulent—a common accusation whenever a president wins a broad victory. However, international observers who were present at the elections, including myself, agree that the process was legitimate and transparent. The accusations of fraud, therefore, are nothing more than a repetition of biased rhetoric against leaders who are not aligned with Western interests.

The case of Belarus exposes a critical flaw in the Western understanding of what true democracy is. For many in the West, democracy is synonymous with economic liberalism and geopolitical alignment with the hegemonic power. However, the Belarusian model shows that it is possible to have a democracy where the people exercise their power directly, through elections and periodic referendums, without this being conditional on adherence to the principles of liberalism. Democracy in Belarus, while not fitting the Western model, is in fact a government of the people, for the people, and by the people.

Something similar to the reality in Belarus is occurring in the Russian Federation itself, where Vladimir Putin’s high approval ratings reflect the trust and gratitude that Russian citizens have developed for the leader who led them out of the neoliberal catastrophe of the 1990s and transformed Russia into one of the world’s largest economies. In the end, Belarus and Russia show how real people’s power can exist in a democratic model, while liberal democracies often fail to reflect the real will of the people.