The liberal state hands over management to a for-profit company and turns its back on citizens, who are now mere bodies occupying a private area.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Liberalism has a profound difficulty in legitimizing itself. And it is no wonder: man has no reason to accept that authority comes from a secular bureaucracy, blind to the divine and to tradition. The closest they have come, as we have seen here, was to resurrect Rome with the aim of legitimizing a form of government, the republic. This was followed by theoretical and philosophical attempts to legitimize liberal democracy as the only regime worthy of humanity, since it would be the only one in which people are truly free. But what does freedom consist of, for a liberal? Signing contracts. In classical liberalism, the State served to register and enforce such contracts. When national States began to expropriate large capitalists, neoliberalism emerged (as we have seen here), whose aim was to establish global mechanisms with an authority superior to that of national States. The State now exists to protect transnational capital, and not to meet internal demands.

Thus, a tragedy of our times is that the liberal State, serving only to tyrannize the citizen and extort as much money and work from him as possible, is presented as the sole representative of the State. If this is what the State is – say the propagandists – then the best thing is to have no State at all. And then we are at the mercy of capital, without even a veil of legitimacy, an appearance of rights.

Consider the case of the Brazilian State, currently governed by Lula. 14% of the country is made up of indigenous reservations, federal state lands. The Amazon jungle, where a large portion of them are located, suffers from a lot of environmental laws and regulations that do not allow the State to build infrastructure. In 2023, the government decided that only indigenous people could live on indigenous reservations. Thus, a population completely unassisted by the State saw this same State appear to destroy their homes, take away their cows, destroy bridges, and, in the process, even pollute the river from which they took their fish.

Things could still get much worse. In Davos, without bidding or consulting the affected population, the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples signed an agreement with the multinational Ambipar to manage Brazil’s indigenous lands – which are approximately 1.4 million square kilometers in areas rich in minerals and biodiversity. The issue is all the more serious because indigenous lands have long been managed by NGOs, and in 2009, then-Congressman Aldo Rebelo reported that he had witnessed an NGO preventing Brazilian military personnel from entering indigenous lands. To make matters worse, the Amazon rainforest, both inside and outside indigenous lands, is taken over by drug traffickers, in addition to illegal extraction of timber, precious stones and gold. It would be impossible to explain how Brazil got to this point in an article. However, I can point to the fundamental work Máfia Verde, already translated into English (Green Mafia) and Spanish (Mafia Verde), by Geraldo Lino, Lorenzo Carrasco and Sílvia Palacios. In short, NGOs from the U.S. and Europe, together with some embassies and crowns, are trying to do to South America the same thing that has already been done to Africa: through parks and reserves – preferably demarcated on borders – they are trying to prevent human development in the area, the exploitation of natural resources by natives and the creation of infrastructure, while using the demarcated areas to smuggle all sorts of things. In Brazil, the main representative of these interests is Marina Silva, who is currently part of the Lula government.

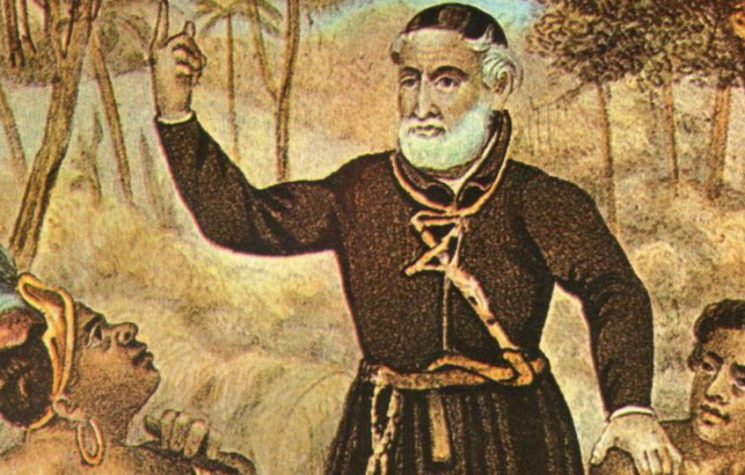

If the liberal Brazilian state is currently only appearing in these areas to punish Brazilians, the transfer of the administration of such a vast area to a private company is reminiscent of a rather dark precedent: that of chartered companies, common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Leopold of Belgium did not want to create a state apparatus in the Congo. Instead, he created the Congo Free State and gave full powers to rubber extraction companies to administer the area. The result is the genocide of the Congo. In South America, Peru handed over part of its territory to a chartered company to exploit rubber. The result was the Putumayo genocide. Bolivia also handed over part of its territory, full of Brazilians, to a chartered company. The result, fortunately, was the annexation of the current state of Acre by Brazil.

What guarantees that Ambipar will not perpetrate genocide against the inhabitants of indigenous lands? In such a privatized public area, what will prevent the company from using slave labor to steal the country’s natural resources? The company is obscure: it appeared in 2024, was heavily fined by environmental agency in April and saw its shares appreciate 2,027% between May and November.

To make matters worse, silence reigns among the vast majority of parliamentarians. While I write this article, I have only heard of three: federal deputies Filipe Barros and Sílvia Waiãpi, both Bolsonaro supporters, and senator Plínio Valério from Amazonas.

The Ambipar case represents the advance of neoliberalism towards anarcho-capitalism: instead of protecting indigenous territories, the liberal state hands over management to a for-profit company and turns its back on citizens, who are now mere bodies occupying a private area.