American neocon messianism has a particularly notorious trait: the United States of America feels itself to be the savior of the world, therefore self-justifying any actions on a global scale.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

American neocon messianism has a particularly notorious trait: the United States of America feels itself to be the savior of the world, therefore self-justifying any actions on a global scale. So far, nothing new. There is, however, an element that belongs exquisitely to more recent times, to our own day, and which with the advent of the second Trump presidency is becoming stronger and stronger: the Savior Syndrome. A syndrome that apparently affects not only Americans.

About the need of “saving” someone

Beyond irony, we are talking about something very serious, which psychology and sociology have well analyzed.

The Savior Syndrome is a psychological and relational phenomenon that denotes a pathological predisposition to take responsibility for the well-being of others at the expense of one’s own psychological and emotional health. This behavior is often characterized by a compulsive need to intervene in the lives of others, solving their problems and trying to “save” them from difficulties, even when such interventions are neither required nor desired. Although the savior figure is often idealized, this syndrome hides a number of psychological and sociological mechanisms that, if unrecognized, can lead to serious distortions in interpersonal relationships and serious damage to individual well-being.

The origin of the syndrome is complex and can result from multiple psychological and social factors. One major cause is related to early experiences of family dysfunction: in family contexts characterized by parental abuse, neglect, or psychological problems, the child may internalize the need to “rescue” his or her family members as a survival strategy; in some cases, the individual assumes, from a young age, the role of caregiver, attempting to stem the emotional distress of parents or family members, and thus developing a tendency to solve others’ problems as a way to gain affection or recognition. In parallel, other psychological origins may include a desire to compensate for internal emotional deficiencies. Those who suffer from low self-esteem or who have failed to build a solid emotional identity may seek to define their own worth through “rescuing” others. Such behavior becomes a form of self-affirmation: saving others provides a sense of importance and social approval that fills the emotional and affective void.

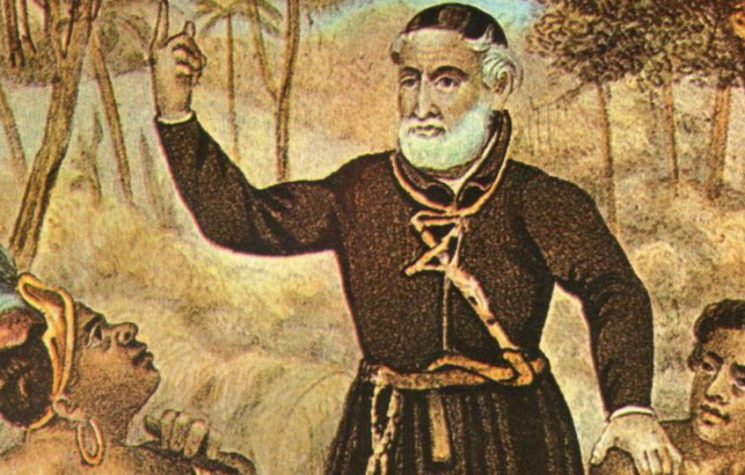

The syndrome can be influenced by a cultural context that emphasizes values such as altruism and self-sacrifice, sometimes in a distorted way. In some cultures, the figure of the savior is idealized and associated with superior moral qualities, creating strong social pressure for individuals, particularly women, to accept the role of “caregiver” or one who solves the problems of others. This context contributes to the perception that being indispensable to others is synonymous with personal fulfillment and value.

One of the main features of the syndrome, then, is the persistent difficulty in setting emotional and practical boundaries. People suffering from this syndrome tend to embrace an excessive sense of responsibility for others, even to the point of sacrificing their own physical and emotional well-being. The inability to say “no” or set clear boundaries leads to a continuous invasion of one’s space and time by others, resulting in a depletion of personal resources.

This phenomenon can be observed in multiple contexts, from family relationships to romantic and professional ones. In a couple relationship, for example, a person with Savior Syndrome may feel compelled to solve the other partner’s problems, even when they do not require outside intervention or are not ready to change. The effect of such a dynamic is a progressive unbalancing of the relationship, with the “savior” person finding himself or herself in a dysfunctional relationship, where the other person does not develop the ability to deal with his or her own difficulties independently, creating a form of emotional dependence.

In the work environment, this syndrome may manifest itself as excessive dedication to the needs of other colleagues or superiors, at the expense of one’s own professional goals. The rescue person tends to take on unsolicited burdens, trying to resolve others’ conflicts, which can lead to work overload and a lack of recognition for one’s efforts.

Another key aspect of the Savior Syndrome is the continuous search for approval. Indeed, the savior often sees himself or herself as the one who does something good and necessary for others, and thrives on the approval he or she receives in return. This behavior is related to the need to gain a sense of worth through external recognition. The satisfaction derived from helping others can become an obsession, creating a spiral in which the individual tries harder and harder to “save” others, without ever stopping to reflect on his or her own needs.

The psychological implications of the Savior Syndrome are many and potentially harmful. First, those who engage in this behavior chronically are likely to suffer from emotional exhaustion and stress. Excessive commitment to others, without ever taking time for oneself, can lead to true burnout. The individual then finds himself or herself facing a constant feeling of fatigue, frustration and inadequacy, often failing to recognize the need for self-care.

Another psychological consequence is the risk of developing anxiety disorders and depression. Because the “savior” constantly devotes himself or herself to others without ever stopping to reflect on his or her own well-being, a condition of emotional disconnection is created that can result in deep sadness or an identity crisis. The person may come to feel alienated, as if they no longer have an emotional space of their own, reducing their value to what they can do for others.

On the relational level, Savior Syndrome can lead to a progressive deterioration of emotional ties. The lack of boundaries and continuous self-sacrifice create dysfunctional dynamics, in which the relationship is based on emotional imbalance. The “saved” person may feel overwhelmed by the continuous support and, paradoxically, develop a form of dependence or resentment toward the “savior.” This relational dysfunction can result in conflict, resentment, and ultimately emotional estrangement as both parties involved end up unable to meet their own authentic needs.

A Stars and Stripes Syndrome

After this necessary examination to introduce the pathology, we must turn to the geopolitical analysis.

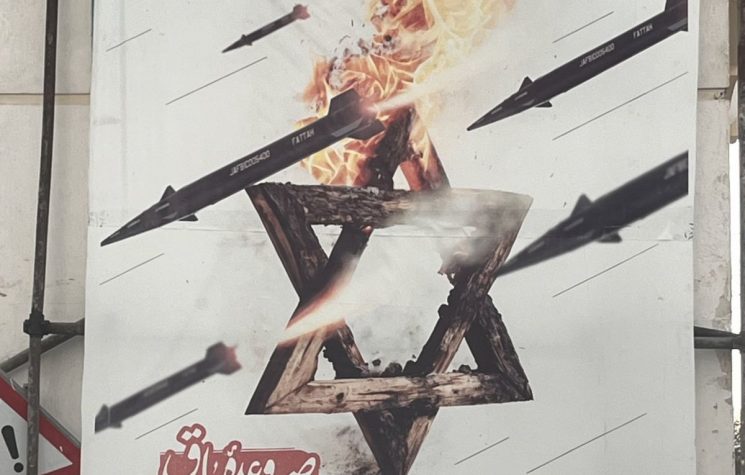

The problem, in fact, is not only American. It is entirely legitimate – we can say – that the United States is pervaded by this syndrome, because it belongs to it constitutively. The long messianic Christian tradition, linked to the evangelical and Pentecostal movements, which make Zionism the centerpiece of their political theology, has been an integral part of the American spirit since the first Puritan English outcast settlers were sent there.

The important question and observation we need to make, however, concerns the spread of this syndrome outside the U.S. There is a certain tendency to admire, revere and celebrate the new American president as a kind of savior. Not everyone agrees on what the object of this salvation is: some say from liberalism, some say from the triumph of communism, some say he wants to save the world from aliens and the economic crisis, some say he wants to revive fascism, and some believe he is the Messiah incarnate ready to defeat the New World Order. The interpretations are many and all would be worthy of in-depth study (for psychologists and sociologists, clearly).

The question that arises, however, is why? What do you see as so salvific about Donald Trump?

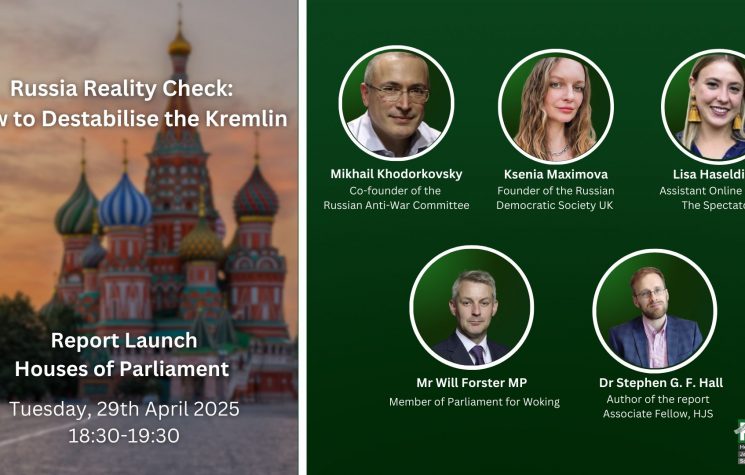

Here we enter the analysis of a kind of political egregora on a global scale. The U.S. has established a dominance so strong that it has altered the collective consciousness of entire peoples. Whether we like it or not, the U.S. first exploited the mind as a domain of warfare (cognitive warfare), understanding that information was the essential weapon (infowarfare). Of course, the U.S. is certainly not the first “dictatorship” or “tyranny,” nor is it the first historically to have understood that one must rule people’s heads before ruling their bodies, but it is equally true that the U.S. has been able to exploit the coincidence of technologies and mass societies to its advantage, succeeding in doing something that had not been done before.

Here we find, for example, Russians extolling Trump as if he were some kind of global peacemaker, ready to defeat liberalism, defenestrate corruption, put peace on all borders, and make the planetary economy fairer. Little does it matter if it was Trump who was the first to support the conflict against the “communist monster” of Russia for years, even deceiving about Ukraine with and usual campaign nonsense. Or even the Europeans, as is the case in Italy, celebrating Trump as “the least worst” who will “do something good” while forgetting that he is about to send the country to war, the very country he loves so much that he keeps it under the yoke of military, economic and political occupation, inviting the prime minister to be a maid at the presidential inauguration.

It appears to be a kind of extension of the spell that was already there and seems to have regained strength. The allure of the star-spangled banner does not change. The “American dream” is still alive and is offered to all.

There is clearly something unbalanced about these positions. Having to go beyond personal enthusiasms and institutional celebrations, which are justifiable though, one has to look further afield. What is behind all this? How is it possible that countries whose populations are still openly subjected to colonization, attack, threats, violence, induced poverty, deprivation of sovereignty etc., were so quick to extol the new American president?

It feels like being in a stadium watching a soccer game (Italians will understand these words well): there are two teams competing for victory. The fans are doing their duty, they are in conflict with each other, even violent conflict, and they are ready to celebrate their team, whether they win or lose. But the fans are unaware that they are victims of a great farce, of a game, made to entertain, a game in which the real winners and gainers are the match organizers, who do not sit among the stands or even on the bench among the players.