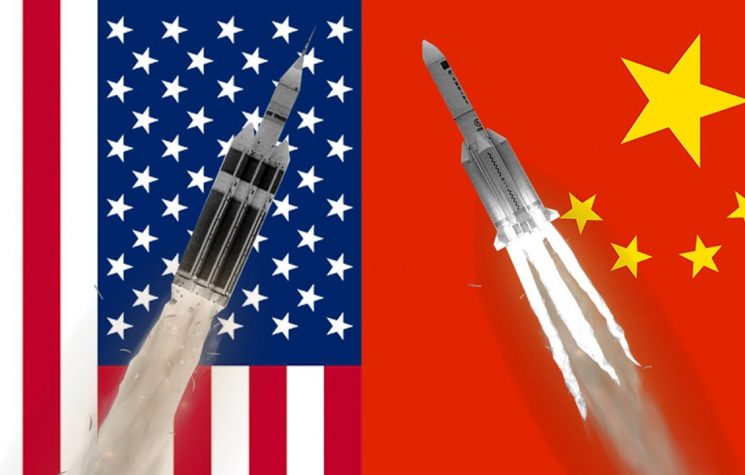

China is racing for the top spot, while the United States of America seeks to open new shores of conflict beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The fourth geopolitical domain, space, has never been closer. China is racing for the top spot, while the United States of America seeks to open new shores of conflict beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

The fourth domain

In Geopolitics, there are five domains of warfare: land, water, air, outer space and infosphere. The fifth domain is artificial, man-made, while the other four are all naturally occurring. The fourth domain, space, was the subject of a real race to conquer it during the 20th century: we all remember the adventures of astronauts like Yuri Gagarin, the Sputnik launches, NASA’s Apollo missions, etc. Space entered the collective imagination thanks to a powerful mass media propaganda effort, made possible through the massive use of film, radio and television, and then employing the unparalleled Internet.

Today thinking about space is normal and almost taken for granted, but geopolitics is not like movies or video games. Going to space is an endeavor for everyone on the planet, in research and exploration, as well as in… conquest.

In recent years, space has become an increasingly competitive and strategic domain, involving both states and private actors. The increasing reliance on satellites, which perform vital functions in civilian (such as communications, navigation, and surveillance) and military domains, has made satellite defense a national security priority. Satellites with dual-use functions are deployed for both civilian and military purposes, such as in the case of remote sensing, which enabled monitoring troop movements during the Russian-Ukrainian SMO as early as the beginning in 2022, highlighting the importance of satellites in military operations.

The space sector has also become an economic opportunity, with the space economy potentially reaching a value of trillions of dollars by 2040. Private companies, attracted by the potential gains, have reduced the cost of producing and launching satellites, contributing to the growth of the market. U.S. legislation, such as the Asteroid Act, has made it easier for private individuals to enter the industry, allowing them to exploit space resources such as asteroids. We all know Elon Musk, who has also become known through his space projects, from SpaceX with its rockets and extra-atmospheric flights to Starlink with its satellites and super-fast internet.

In general, this approach allows states to expand their influence in space without directly managing all operations. An administrative advantage that also poses a risk, however.

Capitalism could not fail to reach out and touch the fourth domain as well.

The space strategy of states is geared toward exploiting space as an economic as well as a military domain, reducing international cooperation in favor of unilateral actions. This process is turning space, once considered a “common good of humanity,” into a geopolitical battleground. Without mincing words, the actions being taken now are now determining the future of global competition.

Space can become the new center of the Earth.

The promise of the new space economy is, in a nutshell, this: where space was the domain of the divine or the unknown, first, and the mask of agonism between empires, then, today private individuals are ready to work, to do business, perhaps from their college dormitory, as in any self-respecting startupper legend. Evident, at this point, what kind of new measurement the Universe contemplates: that of value, of profit. Even beyond the borders of the World, the rules being imposed are the same.

Boundless Imperialism

On the geopolitical level, the United States and China have positioned themselves as major players.

The United States, with projects such as Artemis and Space Force, aims for space leadership, including developments in the defense sector. It is not at all coincidental-and we will talk about this in some future articles-that Elon Musk ended up inside Trump’s entourage: he is the right man in the right place, because he could easily be used to pursue space conquest projects, such as upgrading military and telecommunications systems, depowering NASA and other federal agencies.

The US, in short, already knows that it wants to conquer space as well, extending its hegemony in the fourth domain.

Space has never been a true haven, and satellites have always been at risk. For this reason, many of the nuclear reduction treaties between the U.S. and the USSR included clauses warning against targeting national technical assets or intelligence-gathering satellites. What has changed now is the role that space plays for the United States: it is really a key factor in national security.

For Russia, on the other hand, although space is relevant to some of its national security efforts, it is rather a show of force. Then there is the added complication of China’s strengthening space capabilities. This, coupled with the growing proliferation of interests in counter-space capabilities globally, means that conflict on Earth could spill over into orbit or, alternatively, that misperceptions of activities in orbit could result in conflict on Earth.

While the United States has defined space as a domain of war, it has repeatedly indicated that it does not believe that war in space is inevitable. The U.S. has demonstrated its support for setting norms of behavior and identifying responsible actions in space, both through discussions at the United Nations and through a memo issued in 2021 by U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, which outlines five principles of responsible behavior in space that DOD components must adhere to.

The U.S. is aware that it is not alone in running for space. Whereas in the Cold War period the virtually exclusive competitor was the USSR, today, in an increasingly multipolar world, there are many more adversaries.

Space policy is thus a “lagging” indicator compared to terrestrial policy, because the former inevitably depends on the latter. We do not have a “made-in-orbit policy,” so everything that happens up there is first decided down here. Yet, there is a constant awareness that what happens up there can radically and rapidly change what happens down here.

Now, the question is, if space is a matter of national security, does that mean that the U.S. will rush to conquer, as it usually does, trying to open a conflict front in orbit, so as to channel resources and get the complicated economic machinery of war moving. If this strategy works on earth, why shouldn’t it work in the sky?

Under President Trump’s administration, the U.S. space program has seen significant developments and a renewed focus on lunar exploration. One of the key initiatives was the Artemis program, which aimed to return humans to the moon by 2024 or 2026, marking the first manned lunar landing since Apollo 17 in 1972. The Trump administration has strengthened NASA’s role by increasing the space agency’s budget by 10 percent, which has helped fund key projects, including the development of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon that successfully transported astronauts to the International Space Station in 2020. In 2017 Trump had also signed a directive to resume manned lunar exploration, canceling the previous administration’s asteroid mission.

Keep in mind that Trump played a key role in the creation of the Space Force, the new military branch focused on securing U.S. assets in space and preparing for the possibility of space war. The Space Force budget grew dramatically, increasing by more than 700 percent from 2019 to 2024, while continuing to build satellite systems for defense and countering threats in space.

Despite Trump’s lack of direct attention to space during the campaign, his administration has pursued ambitious space initiatives.

Looking ahead, NASA will pursue missions such as the Perseverance rover to Mars and the Europa Clipper mission to Jupiter. Trump’s legacy in the space sector, now that he will take office again, could see a rapid expansion.

Given the crazy statements about Greenland and the Gulf, it would be no surprise if Trump-or Musk-announced a willingness to conquer the Moon or Mars to export star-spangled “democracy” there.

Just imagine: you have the opportunity to export the rules-based order to other planets as well, could you possibly pass up such a golden opportunity?

The Red Dragon flies high

For its part, China, while also aiming for space supremacy, focuses more on developing counter-space weapons as a deterrent.

Since the beginning of the space race, China has wanted to be part of the exclusive circle of space-faring countries that also have significant global influence. Originally, the necessary technological steps were insufficient, but the substantial progress made over the years has helped to position China as a key competitor in the ongoing space race. This is evidenced by the establishment of the Tiangong Space Station in low Earth orbit (LEO). With the possible decommissioning of the International Space Station around 2030, China is poised to become the only country in the world with a government-run space infrastructure if there are no new developments. Meanwhile, the U.S. administration and NASA are shifting their focus to lunar exploration and beyond, planning to rely on commercial space stations after the ISS. The successful return of samples from the lunar surface by Chang’e 5 in 2020 has solidified the country’s status as the third to succeed, after the Soviet Union and the United States.

China has effectively structured its public agencies and has recently begun to develop its commercial sector: it has recently developed hundreds of commercial space companies, some of which have garnered considerable global attention; it has first and foremost wanted to promote growth within the BRICS+ and lead space cooperation initiatives (still under development); in terms of future exploration, China has decided to partner with the Russian Federation to develop the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS); and as the project evolves, China is positioning itself as a leading country, with the goal of attracting other countries and organizations to collaborate. These include entities such as the Asia-Pacific Cooperation Organization (APSCO), founded in 2008 and headquartered in Beijing, which includes the following members: Bangladesh, Iran, Mongolia, Pakistan, Peru, and Thailand. The cooperation scheme for ILRS contrasts with NASA’s approach for the Artemis program, which has already seen 36 countries sign Artemis Agreements.

What’s more, the Red Dragon country has stepped up efforts to create international partnerships, launching a public call for partners and collaborations and establishing the International Lunar Research Station Cooperation Organization (ILRSCO) based in Hefei, Anhui Province, also called Deep Space Science City. This initiative indicates a departure from previous models, emphasizing a distinct management and collaboration scheme for the development of ILRS that departs from NASA’s method. The stakes are larger than mere space exploration.

China has made sky and space dominance a prerogative of its overall military strategy (more on this in a future article).

The space program of the People’s Republic of China is overseen by the China National Space Administration (CNSA). China’s space program has succeeded in creating and launching thousands of artificial satellites, manned space flights and an indoor space station. Chinese President XI Jinping has also expressed China’s intention to explore the Moon, Mars and the rest of the solar system. This is seen by both China and the United States as part of their strategic competition.

Ahead of upcoming lunar missions and venturing deep into the solar system, China has invited proposals for its Chang’e 7 lunar south pole landing and orbit mission. The Chang’e 6 mission has already seen the participation of multiple countries-Pakistan, Sweden, Italy and France. In addition, since 2016, China has signed more than 46 space cooperation agreements or MOUs with 19 countries, regions and four international organizations, including the EU, ASEAN, African Union and many others. China has already built satellites with several countries such as Nigeria (NigCom-1, 2007), Venezuela (VeneSat-1, 2008), Pakistan (PakSat-1R, 2011), Bolivia (Tupak Katari, 2014) and Laos (LaoSat-1, 2015).

Peace beyond borders

The question to ask is: is there a need for competition between the two great powers, China and the U.S., or perhaps a different gear should be shifted into space?

The United States of the new MAGA 2.0 administration does not seem intent on promoting a peaceful future for space. China, which is committed to building a Pax Multipolaris with the other countries adhering to a new world order not based on the rules of the UK-US axis, cannot afford to lag behind and leave the primacy of space to the Americans, because that would be a disadvantageous move for the whole world, which would find itself a victim of US bullying once again.

There is no time to lose. The fourth domain is the race to reestablish the law of correspondence: Sicut in Coelo et in Terra. Just as it will be in heaven, it will also be on earth. Whoever dominates space could become the new global ruler.