The concept of Pentalasia could take on a newly significant role in understanding world events in the Middle East and beyond.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Among the lesser-known geopolitical concepts to the general public is that of Pentalasia, which today could take on a newly significant role in understanding world events in the Middle East and beyond.

The concept in geopolitical doctrine

From a geopolitical point of view, Pentalasia represents a strategic regional configuration of five interconnected states or geographical areas covering Asia, as the name suggests. A sora of multilateral cooperation based on common interests such as security, economic development, political stability and environmental sustainability.

Pentalasia, in this perspective, could emerge as a regional integration project in a particularly strategic area of the world. The states involved could share territorial borders or be united by historical, cultural and economic ties, creating a bloc capable of tackling global challenges in a concerted manner. Their collaboration could be based on an institutional arrangement that promotes political dialogue, economic interchange and peaceful conflict resolution.

A hypothetical example could involve five countries located in a neuralgic region, not like the Middle East, Central Asia or South-East Asia, deciding to come together to ensure energy security, promote regional infrastructure and strengthen their influence in global dynamics. In this context, Pentalasia could act as a counterweight to larger global powers or dominant international organizations.

In addition to the economic and political aspects, it is clear that such a bloc would have important cultural implications, providing a platform for enhancing diversity and strengthening a common identity as well as addressing transnational issues by promoting collective solutions.

Thus, not only a geopolitical entity, but also a laboratory for a new approach to regional governance, based on the balance between interdependence and sovereignty.

Iran as the center of the issue

Let us focus on the Middle East, Pentalasia’s first area of identification.

Let us look at the most important country in the region: Iran.

It is a regional power in its own right and an international power in the style of emerging countries like Brazil and South Africa, to such an extent that the future of the planet is inextricably linked to what happens in Iran. It is the state best placed to dominate the Middle East and, along with Russia, the best placed to monopolies the routes between the Greater East and the Greater West. In many ways, in fact, Iran is a Southern Russia and R1a paternal genetic lines abound (the same ones associated with the Slavic world, the Scythians, the Indo-Aryans, the Volga battle axe culture and the Kurgan culture). In antiquity, the Persian Empire – which corresponds to the sphere of influence of modern Iran – shared borders with the Roman Empire to the west and India to the east, and also dominated the routes to China. This simple fact speaks volumes about Tehran’s historical and geopolitical fate.

During the era of colonial empires, Iran was the only country in the area, along with the mutilated Turkey, that did not fall into foreign hands, although both British (in the Persian and Indian Gulf) and Russian (towards the Caucasus and Caspian) influence was very strong. It was the time of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (the forerunner of today’s British Petroleum) and its influence in the Persian Gulf. In 1925, Reza Khan, prime minister and former general of the Persian Cossack Brigade, organized a coup d’état and established himself as ‘shah’ (an Iranian word related to the Hindu ‘ksatriya’ and meaning something like ‘lord’) of Persia. Because of his affinity with Germany, Reza Shah was forced by the British and the Soviets to abdicate to his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The Allies feared that the Germans, coming in through the Caucasus, could link up with Iran (and thus India and Tibet, where Germany had many sympathizers) and cause serious problems in the British, Soviet and French territories. Moreover, the British already had their eyes on the Trans-Iranian railway as a supply route to the USSR.

Through Persia, Winston Churchill supported the Soviet war effort with huge shipments of military hardware and raw materials. Armand Hammer’s US company Occidental Petroleum (now Oxy) also agreed to take Soviet oil from the Caspian via this route. In 1951, Mohammad Mossadegh was elected Prime Minister of Iran and initiated a sovereigntist program that nationalized Iran’s oil industry and its crude oil reserves, crushing London’s monopoly. The British government, led by Winston Churchill, responded with the first naval embargo on Iranian oil, launched a campaign of economic sanctions to ruin and isolate the country, froze Iranian assets, and conspired with US President Eisenhower to launch Operation Ajax (known in Iran as Coup Mordad 1338) in 1953, essentially an Anglo-American intelligence-sponsored coup. Mossadegh, very popular in Iran, was arrested and his government was replaced by one under the Shah, totally under the command of London and on good terms with Israel, the US and Saudi Arabia. The Iranian regime began to reorganize itself along the lines of the Arab petrol-dictatorships of the Gulf and King Idris’ Libya. For decades, the Shah’s intelligence service, the SAVAK, would terrorize much of the population and would be feared and hated for its brutal tactics in suppressing any opposition to the regime (essentially Shia clerics and communist activists).

Popular discontent culminated in the Islamic Revolution of 1979, led by Ayatollah Khomeini, which established a kind of Shia nationalist theocracy, restored a sovereign political agenda, expelled British Petroleum, formed the Revolutionary Guard and reformed the country. Shortly afterwards, Iran experienced the imposition of war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, supported by the Anglo-Americans, the same ones who betrayed him shortly afterwards. This war, in which Iraq used chemical weapons with the full knowledge of the West, revealed the enormous magnetic power that the Shiite religion wielded over the Iranian masses, giving them the strength to cheerfully make the greatest sacrifices and to undertake kamikaze actions that crushed the enemy’s morale.

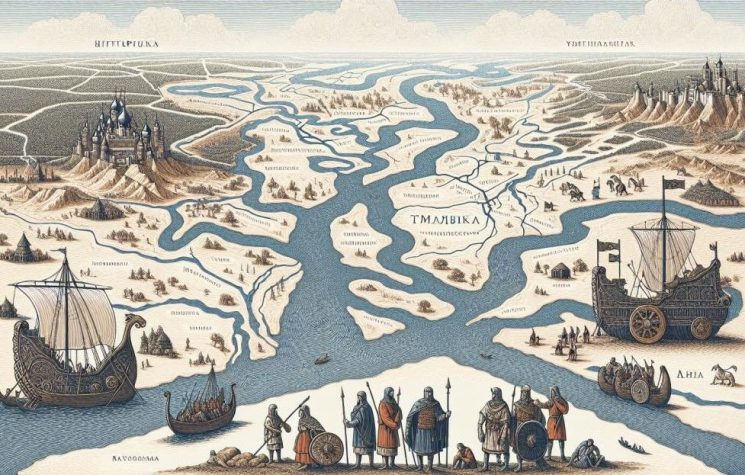

Iran’s role as a nexus does not stop at its east-west hinge. Of all countries with a coastline on the Indian Ocean, Iran is the closest to the Mediterranean, the Caspian, Russia, the Heartland, Israel and the former Soviet space. Its unique position in the heart of Pentalasia (a veritable land of the five seas) makes it a hinge connecting the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf with a delicate geopolitical architecture extending to the Caucasus, Turkey, Israel, Central Asia, Russia and Europe. Pentalasia is, therefore, the hinge region par excellence, connecting five totally different and immeasurably important maritime spaces.

In addition, the region is rich in hydrocarbons. There is probably no other place in the world like it and it is not surprising that it is the most sensitive environment on the planet. It is understandable why Atlanticism is interested in occupying and destabilizing it (Israel, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Kurdistan): if this space were to be structured and stabilized under a sovereign power, this would remove enormous importance from the maritime routes, which are the great resource of the thalassocrat powers.

Iran enters modern history as the only state in the world that possesses seas in the Indian Ocean, the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf, as well as lands in the Eurasian Heartland and Pentalasia.

If we look at the map of Balkanized Eurasia, we see that Iran is also located in the ‘Eurasian Balkans’, the ‘Central Zone of Instability’ and the ‘New Global Pivot’. Iran’s geopolitical role is not only to be a nexus, but also a potential containment wall, thanks to its territory, which for the most part is a mountainous plateau, a kind of natural fortress, an easily defensible, well-populated space (75 million inhabitants, roughly the same as Turkey), with better material and economic means and more population than Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, but with the complicated orography of Afghanistan and excellent sea outlets. By expanding its influence in the Mediterranean, Iran can isolate the petrol-Arab world from the rest of Eurasia and would also be able to cut off Turkey from the resources of the Gulf.

Iran’s regional challenges are the State of Israel, the Arab petrol-monarchies, and the destabilizing presence of the US and UK in the region. Turkey, Israel and the Arab petrol-monarchies aspire to dominate the region by turning it into ‘Pentaland’. Yet, whether they like it or not, geopolitically speaking the most suitable power to do such a thing is Iran, which has already ruled it in the past (Medes, Persians, Achaemenids, Parthians, Sassanids, etc.). Tehran, allied with Syria, Iraq, Lebanon and the Shia, Alawite, Christian, Druze, Ishmaelite, Sufi, etc. communities, could play an important role in the stabilization of this space and thus in world peace. To prevent this, Atlanticism finances Sunni radicalism (especially the Salafist-Wahhabi currents linked to Saudi Arabia, Turkey, the US and Israel) and does its utmost to foment sectarian hatred between Shia and Sunnis, perhaps in the hope of provoking a macro religious civil war in the region.

Iran is also, together with the UAE and Oman, the only Persian Gulf country that also has a coastline in the Indian Ocean. Atlanticism strongly supports the Arab petrol-dictatorships (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the Emirates, Bahrain), but Iran is in a better position than any other country in the world to dominate the Persian Gulf because:

- It dominates the highly strategic Strait of Hormuz, through which 40% of the world’s oil traffic passes (including 40% of China’s oil). If Iran were to close this strait (which would be considered an act of war), the international consequences would be difficult to calculate. Recently, the United Arab Emirates opened a pipeline from the Persian Gulf to the Arabian Sea (part of the Indian Ocean), bypassing Iranian control of the Strait of Hormuz.

- It has more coastline in the Persian Gulf than any other country. The ‘normal’ geopolitical scenario envisages that the Persian Gulf’s commercial and financial activities, which involve a fabulous traffic of capital every day, take place in Iran and that the Persian Gulf’s main financial centre is not Dubai, but the Persian island of Kish (destined to become the Dubai of Iran, also thanks to German architects), declared by Tehran a ‘free trade zone’, in the style of similar zones in China. Kish is home to the Iranian Oil Exchange, a market for oil stocks in currencies other than the dollar (mainly euro, rial, roubles, renminbi and yen), which is almost a declaration of war on the United States, attacking them where it hurts the most: the monopoly on the petrodollar, created out of nothing as an international trading currency. Kish tends to divert attention away from the opulent Emirates city of Dubai, home to the Dubai Exchange – the supreme throne of the petrodollar, which is tightly controlled by the NYMEX in New York (in turn controlled by Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs and other New York and London capitals), the ICE Futures (Inter Continental Exchange), the IPE (International Petroleum Exchange) in London and the London International Commodity Exchange. All these entities conduct their business in dollars. The Kish exchange was opened in August 2011 and used the euro and the Emirati dirham in its first transactions.

- The majority of the population of the Persian Gulf coast is Shia. There is a saying that ‘Islam did not conquer Persia, but Persia conquered Islam’, i.e. that in Iran there has been an Indo-Europeanisation and a de-Semitisation of Islam, leading to Shia religiosity, more hierarchical than Sunnism, with a fully organized clergy and with clear Mazdean, Zoroastrian and Manichean reminiscences. Throughout the Middle East, the Shia are a potential fifth column for Iran: they make up 66% of the population of Iraq and Bahrain (an island petrol-state dominated by a Sunni monarchy that has harshly repressed the Shia majority without the ‘international community’ lifting a finger), 33% of Kuwait, 20% of Saudi Arabia (concentrated in the oil-rich Persian Gulf provinces) and 10% of the Emirates and Qatar. There are also significant Shia populations in Azerbaijan (65%), Yemen (40%), Lebanon (33%) and Syria (15%), as well as in Pakistan, Turkey, India, Afghanistan and other countries. These communities are essential to the backbone of the ‘new Persian empire’ – Iran’s sphere of influence – and make the petrol-Arab regimes very nervous.