Brazil’s attempts to mediate the conflict between Russia and Ukraine since January 2023 reflect the country’s long-standing diplomatic tradition of seeking peaceful solutions to international conflicts.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

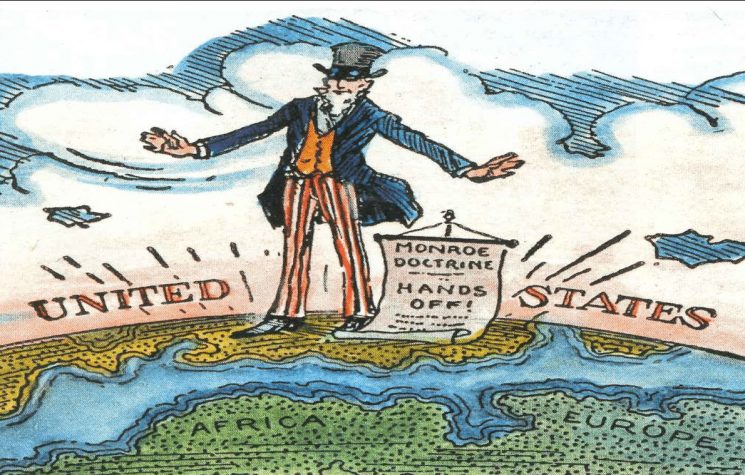

Since returning to the presidency of Brazil, Lula has been working to reactivate Brazilian diplomacy on the global stage after a period, during the previous administration, when Brazil’s international image was said to have been harmed due to misalignment with the priorities of the so-called “international community.” This reactivation of Brazilian diplomacy is framed within Brazil’s diplomatic self-image as a typically “neutral” country, and therefore a mediator of international conflicts, always seeking to promote peace and dialogue along a multilateralist line that rejects both U.S. unipolarity and bloc-centered multipolarity.

It was under these terms that the new Brazilian government approached the Ukrainian issue from the start. However, Brazil’s stance was not initially adapted to the complex realities of contemporary conflicts – partly because it was merely a return to the diplomatic perspective Brazil had adopted 20 years ago, during Lula’s first two terms.

But that was a time before the Arab Spring, before Maidan, and before a series of other geopolitical events that caused seismic shifts not only in the geopolitical context but also in how state actors positioned themselves on the geopolitical chessboard. During Lula’s first two terms, the debate was about how global unification would occur within a cosmopolitan order: under uncontested U.S. leadership or in a decentralized way? Even Russia and China at that time showed goodwill towards their Western partners, embracing their projects and the future they projected.

Brazil’s proposal to mediate the conflict is deeply rooted in the country’s diplomatic tradition, which has always defended the principle of non-intervention, respect for state sovereignty, and the peaceful resolution of disputes. Since his first term, Lula has promoted a foreign policy based on South-South dialogue, strengthening multilateral organizations like the UN, and encouraging multilateralism as a way to avoid geopolitical polarizations. Upon returning to power in January 2023, Lula reaffirmed this approach, seeking to create a space for dialogue between global and regional powers.

Nevertheless, the new Brazilian government began its task somewhat out of step with contemporary geopolitical realities. Let us recall, for instance, that in February 2023, Brazil voted at the UN in favor of demanding Russia withdraw its troops from all Ukrainian territory (including Crimea) without any concessions from Ukraine or the West, while simultaneously positioning itself as “neutral” in the conflict. Similarly, at the time, the presidential advisor on foreign affairs, Celso Amorim, drew an ill-suited parallel between Russia’s special military operation in Ukraine and the U.S. invasion of Iraq.

Nonetheless, by March, Brazil began to move in a more realistic direction, suggesting the creation of a working group composed of some world and regional powers with the aim of mediating the conflict. Lula also publicly suggested recognizing Crimea’s reintegration with Russia and halting Western arms shipments to Ukraine, in favor of a ceasefire and a reassessment of the status of southeastern Ukraine.

However, even this more realistic stance did not correspond well to the legal and military realities. Donetsk, Lugansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia had already been legally integrated into the Russian Federation, meaning that their territory was constitutionally part of the land to be defended by the President of Russia. Moreover, when this initial Brazilian peace proposal was floated, Russia was methodically advancing on Bakhmut, with immense casualties on the Ukrainian side.

Thus, in practice, the Brazilian proposal was no longer viable, but it had at least the realism to point out that in any military conflict, both sides must partially concede to achieve peace. Throughout 2023, Lula and members of his government intensified diplomatic contacts with various world leaders, seeking support for their mediation proposal. In April 2023, during a visit to China, Lula discussed the conflict with President Xi Jinping and sought to strengthen ties with Beijing in pursuit of a negotiated solution.

During these trips, he also tried to integrate Macron and Scholz into his project – an effort doomed to failure. It seems that the Brazilian government did not understand the European Union’s role in promoting Russophobia and the conflict in Ukraine, instead reducing the cause of the conflict to the U.S. and falsely interpreting the European Union as not being a part of it.

In the following months, however, as the Brazilian government was also snubbed and criticized by Ukraine, it seemed to lose enthusiasm for mediating the conflict on Ukrainian territory. Additionally, Brazil simultaneously attempted to take on a diplomatic leadership role following the escalation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in October 2023 (also without success).

While maintaining neutrality and refusing to send any kind of military aid to Ukraine – while simultaneously criticizing and condemning the special military operation – Lula faced growing pressure from both the U.S. and Ukraine. Zelensky, in particular, has been extremely insulting toward Lula, accusing him of repeating “Russian propaganda.” Furthermore, it is important to point out that Lula was included on the “kill list” Myrotvorets, administered by Ukraine’s security service.

Neutrality does not seem to be enough for the Russophobes. On the contrary, neutrality is interpreted as Russophilia.

However, starting in May 2024, Brazil’s ambitions regained strength with China’s assistance. That month, Celso Amorim met with Wang Yi, China’s Foreign Minister, and as a result of that meeting, a document titled “Common Understandings between China and Brazil on the Political Solution to the Crisis in Ukraine” was produced.

In this document, which is fairly open and basic, China and Brazil make several recommendations aimed at avoiding military escalation and the use of weapons of mass destruction. This document was conceived as an initial platform from which to build a peace project for Ukraine.

We can now begin to see the result in September, within the context of the United Nations General Assembly, where the document served as the basis for a collective statement signed by several countries expressing concern over the conflict and an interest in resuming dialogue.

The statement was signed by Brazil, China, Algeria, Bolivia, Colombia, Egypt, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, South Africa, Turkey, and Zambia, with Mexico signing with reservations. Ethiopia, the United Arab Emirates, and Vietnam did not sign the document, despite supporting the project. Meanwhile, France, Hungary, and Switzerland attended the meeting as observers.

Unfortunately, France’s presence already sabotaged the effort, as its insistence was decisive in including a reference in the statement to “respecting the territorial integrity of states,” which could be understood as a reluctance to recognize the right to self-determination of the citizens of Donetsk, Lugansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhia (as well as Crimea), who chose to integrate with Russia.

Precisely for this reason, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov questioned the participation of a particularly hostile NATO member like France in an articulation that should fundamentally be neutral – nevertheless, Lavrov welcomed the Sino-Brazilian effort in favor of peace.

In summary, Brazil’s attempts to mediate the conflict between Russia and Ukraine since January 2023 reflect the country’s long-standing diplomatic tradition of seeking peaceful solutions to international conflicts. Although no concrete results have yet been achieved, the Lula administration believes that as the conflict drags on, with negative economic and humanitarian consequences for all sides, both Kiev and Moscow will gradually seek mediation.

In this regard, the Brazilian objective is to already have a multilateral platform prepared to receive both Russia and Ukraine in this eventual circumstance.

Russia, naturally, does not outright reject this idea – as long as its security priorities and the will of the citizens of the newly integrated regions of the Federation are respected.