By Joseph TREVITHICK

❗️Join us on Telegram ![]() , Twitter

, Twitter ![]() , and VK

, and VK ![]() .

.

A U.S. Navy briefing slide is calling new attention to the worrisome disparity between Chinese and U.S. capacity to build new naval vessels and total naval force sizes. The data compiled by the Office of Naval Intelligence says that a growing gap in fleet sizes is being helped by China’s shipbuilders being more than 200 times more capable of producing surface warships and submarines. This underscores longstanding concerns about the U.S. Navy’s ability to challenge Chinese fleets, as well as sustain its forces afloat, in any future high-end conflict.

In a statement to The War Zone, the U.S. Navy has confirmed the authenticity of the slide, seen in full below, which has been circulating online.

The most eye-catching component of the slide is a depiction of the relative Chinese and U.S. shipbuilding capacity expressed in terms of gross tonnage. The graphic shows that China’s shipyards have a capacity of around 23,250,000 million tons versus less than 100,000 tons in the United States. That is at least an astonishing 232 times greater than the United States.

U.S.-based shipbuilding capacity was in decline even before the end of the Cold War, but steadily shrunk even more afterward. It is at a particularly low point, across the board, now.

The slide also includes a note about the relative “naval production % of overall national shipbuilding revenue” for each country, and that this is estimated to be over 70 percent in China. The stated estimated percentage for U.S. shipyards is clearly legible in the versions of the slide available online, but it appears to be 95 percent.

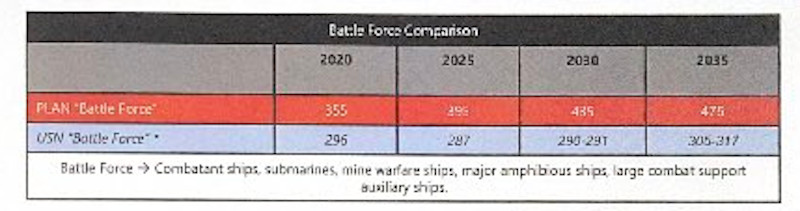

The slide also includes projected sizes for the U.S. Navy and PLAN “battle forces” – defined as the total number of “combatant ships, submarines, mine warfare ships, major amphibious ships, [and] large combat support auxiliary ships” – for every five years between 2020 and 2035. It says that as of 2020, the PLAN had 355 battle force ships and the U.S. Navy had 296. By 2035, the gap between the figures for China (475) and the United States (305 to 317) widens substantially.

China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy is already the largest in the world in terms of total vessels and is steadily acquiring a range of more modern and capable designs, including a growing fleet of aircraft carriers. The figures provided show the size gap between China’s naval fleets and those of the United States only continuing to grow.

It is important to note up front that the slide presents estimates and projections, and that gauging shipbuilding capacity is a complex and multifaceted affair, in general. For instance, is unclear how the naval percentage of total shipbuilding revenue was calculated.

How ships are categorized can often be a point of debate, as well, though this often does not impact whether or not ships fall into a broader “battle force” definition. As a relevant example, the PLAN’s Type 055 warships, its most modern and capable surface combatants, are typically described as destroyers. However, the U.S. Navy often refers to them as cruisers based on their displacement and other features.

The U.S. Navy itself has acknowledged that the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) slide does not reflect a definitive data set and is, at least in part, a living document.

“The slide was developed by the Office of Naval Intelligence from multiple public sources as part of an overall brief on strategic competition,” a U.S. Navy spokesperson told The War Zone. “The slide provides context and trends on China’s shipbuilding capacity. It is not intended as a deep-dive into the PRC [People’s Republic of China’s] commercial shipbuilding industry.”

“It’s been iterated on over time and the unclassified sources used most recently were commercially-available shipbuilding data, publicly-available U.S. Navy long-range shipbuilding plans from the 2023 Presidential Budget (PB23), and the publicly-discussed approximate projected future PLAN [People’s Liberation Army Navy] force,” that spokesperson added.

With this in mind, it is worth pointing out that the slide’s projections and estimates are heavily influenced by the inherently dual-purpose nature of China’s state-run shipbuilding enterprise.

“PLAN surface ship producers are mixed military commercial” and “most PLAN-associated construction [is] completed in CSSC [China State Shipbuilding Corporation] facilities,” the slide says. “China is the world’s leading shipbuilder by a large margin” and the country “controls ~40% of [the] global commercial shipbuilding market.”

Still, some examples do exist. U.S. shipbuilder General Dynamics NASSCO is a prime example, with its two main business areas being large commercial cargo and tanker ships and auxiliaries for the U.S. Navy. The design of the U.S. Navy’s Lewis B. Puller class of seabase ships is derived directly from NASSCO’s Alaska class oil tanker.

The U.S. Navy’s Lewis B. Puller class seabase ship USS Hershel “Woody” Williams, a design derived from a commercial oil tanker.

In addition, the slide’s overall battle force figures do not directly line up with other official U.S. military data. The long-term shipbuilding plan that the U.S. Navy published in March 2019 indicated that the service would have 301 battle force vessels in the coming fiscal year. The Pentagon’s annual report to Congress on Chinese military and security developments in 2020 put the respective Chinese and U.S. Navy battle force figures at 350 and 293.

The most recent report on China from the Pentagon, published last year, says that the PLAN’s battle force inventory was 340 vessels in 2021. The U.S. Navy’s long-term shipbuilding plan for the 2024 Fiscal Year, released earlier this year, says the service expects to have 293 vessels in its battle force in the upcoming fiscal cycle (which starts on October 1, 2023). That same document says that it could have as many as 320 or as few as 311 battle force vessels by Fiscal Year 2035 depending on what courses of action are pursued.

These discrepancies are relatively minor and do not change the fact that there is clearly a major and widening gap in battle force sizes between China and the United States. Still, they do highlight the complexities of comparative counting of naval inventories, which change regularly as older ships are decommissioned and new ones are brought into service, especially based on publicly available information. Beyond that, it is important to point out that a realistic accounting of China’s naval forces is not limited to the PLAN.

In fact, last year, the Pentagon noted that the PLAN’s battle force inventory had actually shrunk in 2021, but that this was due to the fact that 22 Type 056 corvettes had been transferred to the country’s Coast Guard. These are 1,500-ton-displacement warships that, at least in PLAN service, had been armed with anti-ship and surface-to-air missiles, among other weapons. That kind of armament is atypical of vessels in service with most other coast guards around the world, including the U.S. Coast Guard.

A true discussion of China’s current and future naval capacity would have to include at least some ships from its Coast Guard and a number of other nominally civilian maritime security agencies, as well as the country’s substantial maritime militia.

The U.S. military has made its own moves in this regard in recent years. The U.S. Navy, U.S. Marines, and U.S. Coast Guard notably put out a tri-service “naval forces” white paper in 2020. Since then, there has been a clear push to increase routine Coast Guard maritime operations abroad together with the Navy and independently. This has included sending Coast Guard ships to patrol in areas of the Pacific where China has extensive and largely unrecognized territorial claims, like the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait.

None of this necessarily changes the overall direction of the trend line. U.S. military officials, members of Congress, and naval experts have all been drawing attention to the widening gap in total size between the U.S. Navy and the PLAN, as well as concerns about shipbuilding capacity, for years now.

“They have 13 shipyards, in some cases their shipyard has more capacity – one shipyard has more capacity than all of our shipyards combined,” Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro told members of Congress at a hearing in February. “That presents a real threat.”

Overall shipyard capacity has a massive impact on sustaining ships. The ONI slide now circulating online includes a note that “50+ dry docks can physically accommodate an aircraft carrier.” The PLAN is working hard to increase the size of its carrier fleets and this also reflects yards that could be used to conduct work on other larger surface ships and submarines.

Shipyard capacity for sustainment of existing fleets is also something that has been a subject of great concern in the United States for some time now. After decades of cutting back on spending, the U.S. Navy has been trying to explore ways to alleviate those issues, including by modernizing its own remaining shipyards and expanding its use of commercial yards to conduct various types of often sensitive work. Reflecting the trend of shipbuilding capacity increasingly being found outside of the United States, the latter category could eventually include more foreign-owned and operated yards, including ones in Japan, too.

Shipbuilding is also a complex and costly affair that requires large amounts of skilled labor and resources, which can take significant time to source. Delays or other hiccups in shipbuilding, as well as repair and overhaul work that requires shipyard capacity, can easily cascade. This reality has manifested itself to an especially extreme degree for the U.S. Navy when it comes to submarine maintenance.

Rear Adm. Jonathan Rucker, the Navy’s Program Executive officer for Attack Submarines, told reporters in November 2022 on the sidelines of the Naval Submarine League’s annual conference that 18 of the service’s 50 attack submarines of all classes were undergoing or awaiting maintenance at that time. This is significantly higher than the service’s target of having no more than 20 percent of all attack submarines down for maintenance at a time.

The Los Angeles class attack submarine USS Boise, which was first commissioned in 1992, has become an unfortunate poster child for these issues. Boise has been sitting pierside since 2017 and when it hopefully returns to active duty next year it will have spent around 20 percent of its entire career idle awaiting maintenance.

The Los Angeles class attack submarine USS Boise. USN

In addition, this reality has prompted major concerns with regard to the U.S. Navy’s capacity, or lack thereof, to repair battle-damaged ships and get them back into service relatively rapidly in a major future conflict. The multi-day fire that gutted the Wasp class amphibious assault ship USS Bonhomme Richard while it was in port undergoing maintenance in 2020 reinvigorated discussions about the service’s limited capacity to process damaged ships in an actual crisis. This has only been magnified by the increasing possibility of a major conflict in the Pacific.

“The Navy has not needed to triage and repair multiple battle-damaged ships in quick succession since World War II,” the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a Congressional watchdog, said in a report published in 2021. “After the end of the Cold War, the Navy divested many of its wartime ship repair capabilities, and its ship maintenance capabilities have evolved to focus largely on supporting peacetime maintenance needs.”

“However, the rise of 21st century adversaries,” like China, “capable of producing high-end threats in warfare – referred to as great power competitors – revives the need for the Navy to reexamine its battle damage repair capability to ensure it is ready for potential conflict,” the 2021 GAO report added.

A flow chart from GAO’s 2021 report on US Navy capacity to triage and repair significant numbers of battle-damaged ships.

In February, Navy Secretary Del Toro highlighted how the differences between a democratic United States and a totalitarian China come into play in this part of the equation.

“[W]hen you have unemployment at less than 4%, it makes it a real challenge whether you’re trying to find workers for a restaurant or you’re trying to find workers for a shipyard,” he explained. “They’re a communist country, they don’t have rules by which they abide by.”

“They use slave labor in building their ships, right,” Del Toro also asserted. “That’s not the way we should do business ever, but that’s what we’re up against so it does present a significant advantage.”

Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro speaks at an event in New York in May 2023. USN

As a result, the U.S. Navy has often called into question the basic viability of trying to maintain parity with China on a quantitative level. The service’s senior leadership has often argued against focusing solely on total numbers and for pursuing advanced and novel capabilities, including hypersonic weapons and uncrewed surface and underwater vessels, which will allow it to keep a qualitative edge.

“They [the PLAN] got a larger fleet now so they’re deploying that fleet globally,” Navy Secretary Del Toro said at the hearing in February. “We do need a larger Navy, we do need more ships in the future, more modern ships in the future, in particular, that can meet that threat.”

“For us to pivot, under the budget line that we have right now, to pivot to a more lethal force, we need to give up some stuff,” Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Adm. Mike Gilday, the Navy’s top officer, told reporters in Febraury 2022. “And you can’t just look at it through the lens of surface VLS [vertical launch system] tubes.”

Gilday was responding to a question about the U.S. Navy’s plans to decommission its Ticonderoga class cruisers, each of which has 122 Mk 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) cells that can be loaded with various missiles. The ships typically carry a large load of Tomahawk land attack cruise missiles and represent a significant portion of the service’s current surface-to-surface strike capacity.

All of this of course comes amid concerns about China’s rising military capacity and capabilities, writ large, particularly within the context of a potential future intervention against Taiwan. U.S. officials have repeatedly warned that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) could feel that is capable of succeeding in such a major operation by 2027, if not sooner. Of course, those same officials routinely stress that this does not mean that the government in Beijing is actively planning to act on any particular timeline.

Though The War Zone has not yet been able to confirm this, the shipbuilding slide appears to be from a larger ONI briefing intended for members of Congress that calls for more actively challenging Chinese ambitions over Taiwan and elsewhere. The briefing in question at least contains the same details about China’s control of worldwide commercial shipbuilding and the number of drydocks it has that can fit an aircraft carrier as the unclassified slide that has been circulating online, according to a report last week from Air & Space Forces Magazine.

“‘The survival of Taiwan’s democracy is a critical geostrategic issue that carries long-term consequences for China, the U.S., and the broader international community,’ the ONI said, but ‘the China problem is not all about Taiwan,’ noting that all of China’s neighbors, both on land and sea, are facing military, economic and diplomatic pressures from Beijing which would be extremely hard to hold at bay individually,” Air & Space Forces Magazine reported after obtaining a copy of this larger briefing. It “noted ten geographic areas where China is actively challenging borders and territory, and it is increasingly characterizing itself as an ‘arctic nation’ with rights to exploit resources in that area.”

The briefing also reportedly at least contains the same details about China controlling 40 percent of worldwide commercial shipbuilding and having 50 drydocks big enough to fit an aircraft carrier as the unclassified slide that has been circulating online.

It also warns against China’s use of “espionage, coercion, pressure, subversion, and disinformation” to “shape the international system” and otherwise gain global leverage, that report says.

“We are engaged in an international struggle between competing visions,” the briefing, which carries the signature of ONI head Rear Adm. Mike Studemans, adds, according to Air & Space Forces Magazine. “China is executing a grand strategy, and has been unified in pursuing it comprehensively and aggressively for many years.”

When it comes to the Navy, in particular, ONI is clearly sounding the alarm anew that the startling disparity, which is still rapidly growing, in total fleet sizes and shipbuilding capacity between it and the PLAN is a major concern when it comes to the service’s ability to help challenge the Chinese government’s global ambitions.