While the immediate implications of Guantanamo with regard to the U.S. violations at the base are of paramount importance, the focus on this relic of the U.S. war on terror must not be dissociated from Guantanamo’s earlier history.

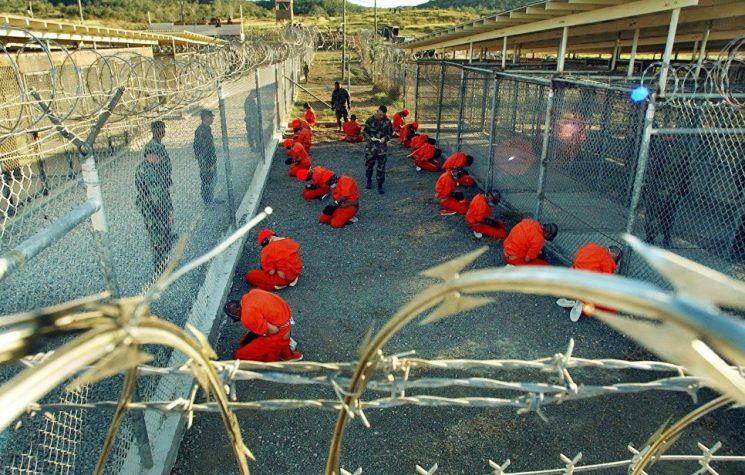

Since the aftermath of September 11, 2001, the U.S. has used its base at Guantanamo, Cuba, to carry out the incarceration and torture of foreign nationals suspected of terror activity. The first detainees arrived in Guantanamo in 2002, after the U.S. ascertained it could without all legal rights, including preventing them from legal recourse against their indefinite detention. Most detainees had been subjected to the CIA blacksites for several years before their incarceration in Guantanamo.

This month marked 20 years since Guantanamo started being used by the U.S. as a torture and detention centre. In 2008, while campaigning for the U.S. presidential elections, Barack Obama had declared he would close down the detention facilities within a year, and instead transfer the detainees to indefinite detention in the U.S. The outcome would have seen Obama bring U.S. atrocities home, sparking opposition from lawmakers.

U.S. lawyer and diplomat Lee Wolosky described the Guantanamo situation as “self-inflicted” in a recent article: “a result of our own decisions to engage in torture, hold detainees indefinitely without charge, set up dysfunctional military commissions and attempt to avoid oversight by the federal courts.”

The ”war on terror” rhetoric no longer holds sway globally as it did a decade ago, yet the U.S. is still to close down the detention facilities – a move unlikely to occur during the Biden administration’s tenure. In December last year, the New York Times reported that the facilities would expand to build a $4 million courtroom. Out of 780 men detained in the facility, 39 remain.

On the anniversary of the first detainees’ arrival in Guantanamo, the Cuban government called upon the U.S. to close the prison, noting that only 12 out 780 detainees have been charged with war crimes. Human rights organisations, former detainees and U.S. lawmakers have reiterated the call.

For the Cuban government, closing down Guantanamo would be just one step in its resolve to have the illegally occupied territory returned to Cuba.

Guantanamo is the oldest U.S. military base abroad. While the use of the facilities has sparked outrage globally, there has been no similar outcry for an end to the U.S. military occupation of Cuban territory. It is the blockade that captured international attention through the UN General Assembly’s non-binding and therefore ineffective, resolutions. But world leaders are intent on ignoring the fact that Cuba is still indefinitely partly occupied by the U.S. – a relic of earlier exploitation of the island at a time when the island faced both U.S. and Spanish intervention against their sovereignty.

Since the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, the Cuban government has consistently denounced the U.S. illegal occupation of Guantanamo. As U.S. efforts

to destabilise Fidel Castro’s revolutionary rule increased, Guantanamo was used as a base from which violations against the island would be carried out, including provocation of Cubans which the U.S. hoped would lead to a direct confrontation. Several Cubans employed at the military base were tortured and murdered by U.S. soldiers stationed at Guantanamo.

Since 1960, a year after the Cuban Revolution’s triumph, the Cuban government has refused the U.S. payments for its use of Guantanamo, signalling the government’s opposition to the U.S. occupation of its territory.

Apart from the brief thaw in relations between Cuba and the U.S. during the Obama administration, when the Cuban Five were released in exchange for USAID subcontractor Alan Gross, the U.S. has maintained a hostile policy against Cuba, exacerbated by the Trump administration and, so far, upheld by current U.S. President Joe Biden.

Article 10 of Cuba’s 1976 Constitution clearly states, “The Republic of Cuba repudiates and considered illegal and null the treaties, pacts or concessions agreed upon in unequal terms that ignore or diminish its sovereignty over any possession of the national territory.”

The U.S. perception of Cuba has not altered since the earlier intention to exploit the island, while the international community has simplified Cuba in terms of the humanitarian impact of the illegal U.S. blockade on the island. While the immediate implications of Guantanamo with regard to the U.S. violations at the base are of paramount importance, the focus on this relic of the U.S. war on terror must not be dissociated from Guantanamo’s earlier history.