The Caravan of Death stands as a forewarning of what was to be unleashed in Chile throughout Pinochet’s rule and its aftermath, Ramona Wadi writes.

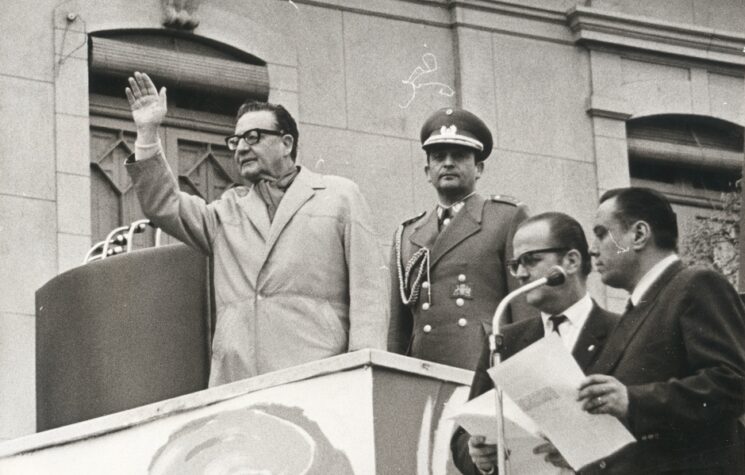

Chile’s September 11, in 1973, brought a brutal end to Salvador Allende’s socialist rule. In its wake, violence permeated Chilean society, through the U.S.-backed military coup which was to provide gruesome inspiration for the later regional systematic surveillance and elimination of socialists and communists known as Operation Condor, in which several Latin American countries were involved.

The mass arrests of Chileans loyal to Allende and socialist politics became a long purge in the country. The Caravan of Death – one of the earlier dictatorship operations aimed at instilling terror within the country – was carried out in the coup’s aftermath, between September 30 and October 22, 1973, after securing Santiago by means of brutal suppression, torture and killings. Dictator Augusto Pinochet’s purge was aimed at silencing dissent throughout the country, and also to ensure the military’s loyalty towards the dictatorship – any negligence or lenience exhibited by any individual would be punished by methods used against dissenting Chileans. The ultimate aim, according to retired Lieutenant Colonel Marcos Herrera Aracena, was “to bring an end to the remaining legal processes… In other words, finish with them once and for all.”

The Caravan of Death massacres are considered to be among the most brutal not only due to the extermination methods involved – at times the corpses were unrecognizable due to bludgeoning – but also because many Chileans willingly turned themselves in for interrogation.

Army officers travelled in Puma helicopters throughout Chile, inspecting detention centres and giving orders for execution, or carrying out the executions themselves. Testimony from La Serena indicates that 15 prisoners were executed by firing squad and their bodies buried in a mass grave. To prevent any possible dissemination of knowledge, at least in the immediate aftermath, the official version publicized by the dictatorship was that the prisoners had attempted an escape.

While at first the dictatorship seemed adamant on making its brutality known to quash any resistance, the more refined methods of disappearance and secret extermination sites hastened a culture of impunity and oblivion. The Calama massacres – the last stop in the Caravan of Death – was such an example. Relatives of the disappeared sought information about the whereabouts of their loved ones to no avail. It was the female relatives of the disappeared in Calama who took matters into their own hands and started physically searching for the bodies of their loved ones in the Atacama Desert. The dictatorship had forbidden any leaking of information due to the extent of mutilations the victims had been subjected to by the execution squads. As the women’s resilience increased, so did the dictatorship’s efforts to prevent any discovery of the bodies through exhumation and reburial of remains.

The Rettig Commission established that 75 Chileans were killed and their bodies disappeared throughout the operation, headed by Brigadier General Sergio Arellano Stark, and with the participation of agents Manuel Contreras, Marcelo Moren Brito, Sergio Arredondo Gonzalez, Armando Fernandez Larios and Pedro Espinoza Bravo – all of who played prominent roles in the torture and disappearances of dictatorship opponents throughout Pinochet’s rule. Contreras headed the National Intelligence Directorate (DINA), Brito oversaw torture at Villa Grimaldi, while Fernandez Larios was involved in the assassination of Chilean economist and diplomat Orlando Letelier in Washington, carried out by double agent for DINA and the CIA, Michael Townley.

Although indicted by Judge Juan Guzman Tapia on December 1, 2000 for ordering the Caravan of Death killings, dictator Pinochet escaped justice on account of purported health reasons. In relation to dictatorship memory and rupture, the Caravan of Death stands as a forewarning of what was to be unleashed in Chile throughout Pinochet’s rule and its aftermath. Particularly in Calama, the women’s resilience against the dictatorship can be seen as one of the earliest expressions against the nationwide oblivion through which Pinochet attempted to crush any questioning, let alone investigations, into dictatorship-era crimes.