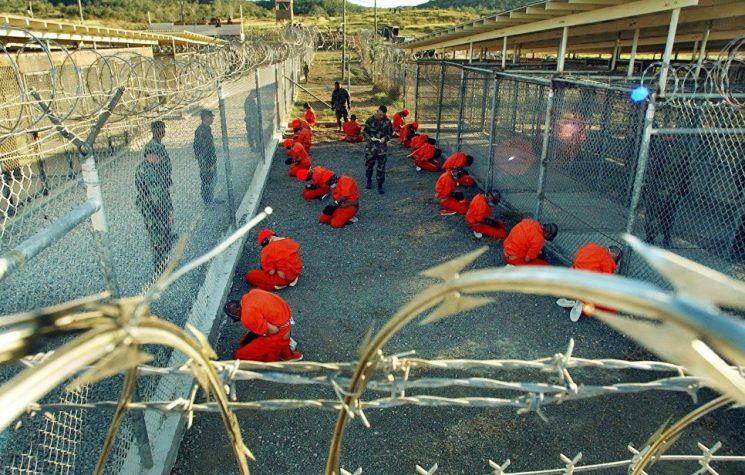

U.S. democracy does not extend to Guantanamo Bay or any of the hideous ‘black sites’ where the CIA and its international partners conducted torture.

President Joe Biden says he is proud that the United States “is back” to being prosperous, visionary, and with enormous military forces to be reckoned with on the world stage (although they didn’t do terribly well in Afghanistan). He is a positive sort of person, even though his outlook has understandably been influenced by considerable personal grief during his long life. Certainly he has made mistakes, the latest being to slap down a CNN reporter who asked him an awkward question, but he followed up by declaring he thinks that media reporters have “got to have a negative view of life, it seems to me. The way you all, you never ask a positive question.”

That’s a pretty ingenuous statement, but he’s absolutely right, and the tenor of U.S. mainstream reporting concerning the Putin-Biden meeting was redolent with regret that there hadn’t been a shouting match. There was frustration that there had been agreement about some matters, albeit modest. Then the topic of the U.S.-Russia summit meeting dropped off the West’s front pages and out of the broadcasting stream simply because it had not been a disastrous failure. It had been an annoying outcome for many people, and especially for supporters of the U.S.-Nato military alliance which is desperately engaged in trying to justify its existence by conjuring up threats around the world.

As American and Nato forces scuttle away from their twenty-year war in Afghanistan, where, as I’ve written before, “they’ve been beaten into the ground by a bunch of raggy-baggy militants who don’t have any strike aircraft or drones or tanks or artillery”, the European leader of Nato, its Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, prodded and supported by the Pentagon, continues to scoot round the world to promote the survival and even expansion of his creaking empire. He stayed home, however, to meet with President Biden on June 14, and it was ironic, to put it mildly, that the main media photograph was of the two of them outside the billion dollar palace that is Nato’s new headquarters in Brussels.

At Mr Biden’s media conference following the Nato summit he carried on highlighting the theme of democracy and declared that “the democratic values that undergird our alliance are under increasing pressure, both internally and externally. Russia and China are both seeking to drive a wedge in our transatlantic solidarity.” Of course, neither Russia or China would give a fig about U.S.-Nato solidarity if it wasn’t specifically intended to threaten both of them. But it must be vexing to be continually lectured by Washington on the subject of democracy.

There is democracy in the United States, and in general it covers the country from north to south and from west to east, from San Francisco Bay to Chesapeake Bay. But democracy doesn’t extend to Guantanamo Bay, the U.S. colonial enclave, military base and detention centre in the Republic of Cuba.

Guantanamo Bay’s prison was established by President GW Bush in 2002 and after a high of 780 prisoners has now 40. Nine died and the others were released. The New York Times of 9 June 2021 reported that of the remaining 40 prisoners “12 are being handled by the military commissions war court — three are facing proposed charges, seven are facing active charges and two have been convicted. In addition, 19 detainees are held in indefinite law-of-war detention and are neither facing tribunal charges nor being recommended for release. And nine are held in law-of-war detention but have been recommended for transfer with security arrangements to another country.” This is not democracy, and it is understandable that the constant preaching from Washington rings false to the point of absurdity.

In Russia there is a detained prisoner called Alexei Navalny, a politician and lawyer who in 2013 and 2014 was awarded a suspended sentence for embezzlement. He is in jail because he was judged to have violated his parole conditions. (This followed his poisoning, allegedly by a toxic agent. The western media have covered the matter in detail, even noting President Putin’s rebuttal of accusations of official involvement.) But Mr Navalny, unlike the hundreds of prisoners who have passed through, died, or remain in Guantanamo Bay, had a trial in an open court of law. Washington’s prisoners in Guantanamo are denied the right to trial, but this and other evidence of vicious persecution are ignored by Mr Biden in favour of criticising Russia over the Navalny detention, such as when he declared in the White House on 14 June that “Navalny’s death would be another indication that Russia has little or no intention of abiding by basic fundamental human rights.”

“Basic fundamental human rights” are most important, but the United States isn’t consistent in applying them or even recognising them. It was, however, encouraging when twenty-four Democratic senators sent a letter to the president on 16 April, stating, among other things, that “indefinite detention at Guantanamo is at its core a human rights problem – one that demands solutions rooted in diplomacy and that uphold U.S. human rights and humanitarian law obligations. . .”

This handful of U.S. legislators noted that all of the 40 prisoners remaining in Guantanamo have suffered “years of indefinite detention without charge or trial; a history of torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment; and multiple attempts at a thoroughly failed and discredited military commission process.”

And in few cases has suffering been more acute and long-lasting and totally destructive than that of Saifullah Paracha who has been in the Guantanamo concentration camp for fourteen years.

In May, Al Jazeera noted that the 73 year-old Mr Paracha, who has diabetes and heart disease, “lived in the U.S. and owned property in New York City, and was a wealthy businessman in Pakistan. Authorities alleged he was an al-Qaeda ‘facilitator’ who helped two of the conspirators in the September 11 plot with a financial transaction. He says he did not know they were al-Qaeda and denies any involvement in terrorism.” And in spite of trying for fourteen years to prove that Paracha was a terrorist, the entire U.S. intelligence system has failed to bring a case against him.

As recorded by reprieve.org, “Saifullah was on his way to Thailand for a meeting with buyers for the retail giant Kmart, in the summer of 2003. He landed in Bangkok, but he never made it to the meeting… He was picked-up at Bangkok airport in an FBI-led operation and rendered to Bagram airbase in Afghanistan.” He wasn’t charged, but was brutally tortured along with countless others in ways described in a definitive report in the New York Times 18 months ago. Democracy, anyone?

U.S. democracy does not extend to Guantanamo Bay or any of the hideous ‘black sites’ where the CIA and its international partners conducted torture. (And torture may well continue, for nobody knows what happens, for example, at the CIA-partnered centres in Lithuania, Romania and Poland which are said to be closed.) The “basic fundamental human rights” so valued by Mr Biden are not much in evidence, and there isn’t any democracy in Guantanamo Bay. Mr Biden says he is proud that the United States “is back”, but it’s up to him to bring back democracy and he’s not had much success, so far.