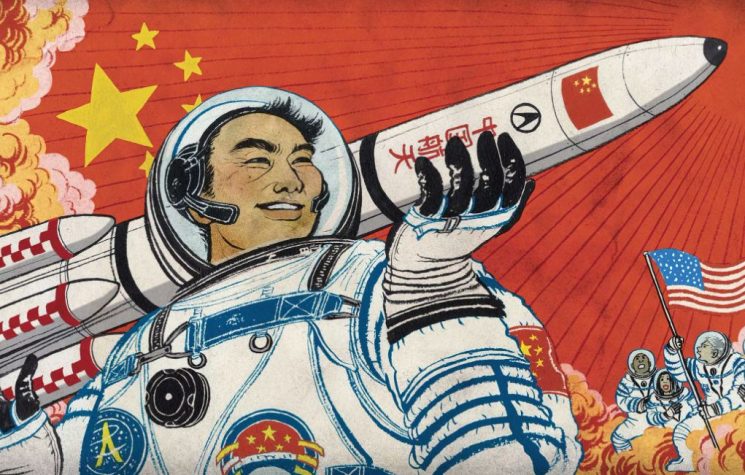

Washington has re-established the “space race” by creation of the Space Force intended to “control the ultimate high ground,” Brian Cloughley writes.

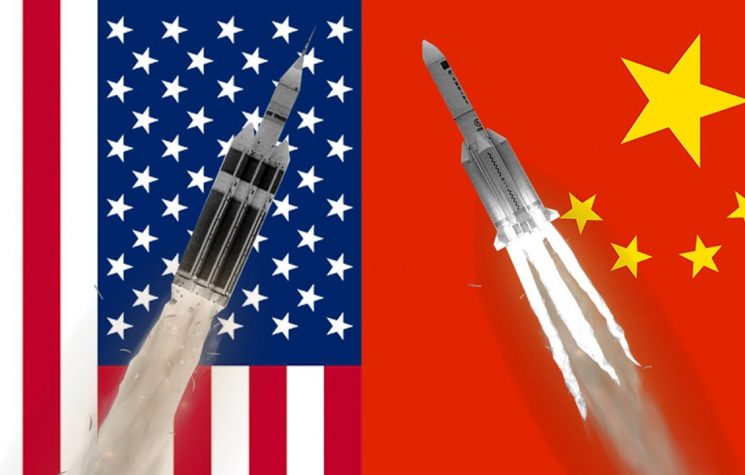

In January it was noted by a New York Times’ columnist that the nominated Secretary of the U.S. Defence Department, General Lloyd Austin, had “told the Senate he would keep a ‘laserlike focus’ on sharpening the country’s ‘competitive edge’ against China’s increasingly powerful military. Among other things, he called for new American strides in building ‘space-based platforms’ and repeatedly referred to space as a war-fighting domain.” This was not a surprising commitment by the about-to-be confirmed head of the Pentagon, which had already added the ominously named Space Force to its war-fighting assets.

Former White House incumbent, Donald Trump, announced creation of the Space Force in December 2019, stating it would be responsible for “the world’s newest war-fighting domain.” He considered that “Amid grave threats to our national security, American superiority in space is absolutely vital. We’re leading, but we’re not leading by enough, but very shortly we’ll be leading by a lot. The Space Force will help us deter aggression and control the ultimate high ground.” His explicit declaration that Washington is prepared to engage in warfare in yet another “domain” was not surprising, but it is regrettable that the Biden Administration shows no sign of reversing the intention to deploy weapons in space.

Russian reaction to establishment of the Space Force was President Putin’s observation that “The U.S. military-political leadership openly considers space as a military theatre and plans to conduct operations there” which is entirely against the letter and spirit of the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, known generally as the Outer Space Treaty. In Article IV of this agreement of 1967, as recorded by the U.S. State Department, “States Parties to the Treaty undertake not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, install such weapons on celestial bodies, or station such weapons in outer space in any other manner.”

111 countries have agreed to abide by the treaty, and the 23 that have as yet failed to ratify it are unlikely to engage in space activities of any sort. The accord was a major step forward during the Cold War, and it was hoped that in later years its provisions might be extended and made more precise and binding, but this was not to be. The attraction of space as a war-fighting domain was too attractive to be ignored by Washington, and in 1982 the U.S. Air Force was directed by President Reagan to form Space Command, known as the “Guardians of the High Frontier” and it is not surprising that members of the new Space Force are also titled “Guardians”. The problem is the mission of these people includes “maturing the military doctrine for space power, and organizing space forces to present to our Combatant Commands.”

There has been no rebuttal of Trump’s definition of space as “the world’s new war-fighting domain,” and no modification of the Space Command Mission to “enhance warfighting readiness and lethality through the integration of space capabilities with the joint force, allies, and inter-agency partners in all domains.” And there is rejection of international moves to reduce the possibility of confrontation in space that could lead to outright conflict.

Unconditional U.S. opposition to peace in space was exemplified by its 2014 rejection of a UN General Assembly resolution on the prevention of an arms race in that domain. It is extremely difficult to see how any government could object to a proposal that calls “on all states, in particular those with major space capabilities, to contribute actively to the peaceful use of outer space, prevent an arms race there, and refrain from actions contrary to that objective.” But sure enough, although 178 countries consider this to be a good thing for the future of the world, and voted for the resolution, the United States and Israel abstained. It is verging on the incredible that these countries would not endorse a proposal that there should be peaceful use of outer space.

There was worse to come in the saga of space militarisation, for in November 2020 the First Committee of the UN General Assembly received no support from the U.S. for further initiatives that could guide the world away from the disaster that will befall us if there is no check on movement to “war-fighting” in space. Five resolutions were put forward concerning the furtherance of peace in space, and the U.S. voted against four of them, including the one that specified there should be “No first placement of weapons in outer space.” It seemed that the then U.S. administration actually favoured placement of weapons in space, and it is woeful that the Biden administration has not made it policy to cease militarisation of Trump’s “war-fighting domain”.

April 12 is the International Day of Human Space Flight, marking an important anniversary, not only of technical achievement but of a hoped-for dawn of international cooperation. The UN notes that in 1961 there was “the first human space flight, carried out by Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet citizen. This historic event opened the way for space exploration for the benefit of all humanity.” Formalisation of the anniversary was declared by a UN General Assembly stressing that celebration is merited because of international desire “to maintain outer space for peaceful purposes,” and the U.S. representative declared that the “cold war space race is over and we have all won”.

Unfortunately, the Cold War has been resumed by Washington, and the “space race” has been re-established by creation of the Space Force intended to “control the ultimate high ground.”

The fact that the International Day of Human Space Flight involves remembrance of a Russian astronaut is enough to keep the anniversary out of the U.S. mainstream media, and this affected reporting of an important statement made on that day last month.

Russia’s foreign minister Sergey Lavrov reiterated Moscow’s space policy by stating “We consistently believe that only guaranteed prevention of an arms race in space will make it possible to use it for creative purposes, for the benefit of the entire mankind. We call for negotiations on the development of an international legally binding instrument that would prohibit the deployment of any types of weapons there, as well as the use of force or the threat of force.”

The policy could not be clearer. And it was followed by a similar declaration by China’s Zhao Lijian that “We are calling on the international community to start negotiations and reach agreement on arms control in order to ensure space safety as soon as possible. China has always been in favour of preventing an arms race in space; it has been actively promoting negotiations on a legally binding agreement on space arms control jointly with Russia.”

On February 22, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in a speech in Geneva that the U.S. should “engage all countries, including Russia and China, on developing standards and norms of responsible behaviour in outer space.”

Even if Blinken’s words fall well short of equating “responsible behaviour” with any indication of a commitment to refrain from placing weapons in space, he did conclude that “I pledge that the United States is here to work, cooperate, and once again use the Conference on Disarmament to create bold, innovative agreements to protect ourselves and each other.”

Well: get on with it, Secretary Blinken. Start talking with people rather than at them. You might even manage to convince your own Space Guardians that peace is better than war.