If Israeli energy firm Energix is successful, a sprawling complex of wind turbines will soon cover up to a quarter of the agricultural land still under the control of Syria’s indigenous Golan residents.

by Jessica BUXBAUM

On December 9, Israeli police fired tear gas and rubber bullets at hundreds of Syrians peacefully demonstrating against the development of a wind farm in the occupied Golan Heights.

Ten protesters were injured and eight arrested. According to Al-Marsad, the sole human rights organization in the occupied Golan, the Golan Association for the Development of Arab Villages’ medical clinic received 12 cases of protesters with rubber bullet wounds—some on the upper body and face. Dozens of demonstrators suffered from gas inhalation. According to the police, officers responded with “non-lethal weapons” and four officers were injured from stones being thrown.

The violent confrontation capped off a week of heavy police presence in the Golan Heights. Officers were there to escort employees from Israeli company Energix Renewable Energies as they took soil samples using drilling machines for their wind turbine project being built on Syrian land.

Police road closures prevented 1,000 Syrian farmers from accessing their land. Demonstrators say the excavation work damages agriculture.

Syrian Druze say the wind farm will disrupt their way of life

The December 9 protest was part of a general strike in the Syrian Druze communities against Energix and the police. But the Syrian struggle against Energix stems as far back as 2018 when Energix was in the final stages of getting its wind turbine project approved.

Now, the wind farm is underway after being approved by Israel’s National Committee of Infrastructure (NIC) and all government ministries despite strong opposition to it from the local residents.

“[This project] will have bad effects for our land, our environment and for us as farmers and human beings,” Emil Masood, an activist and cherry farmer who is organizing against the wind farm, said.

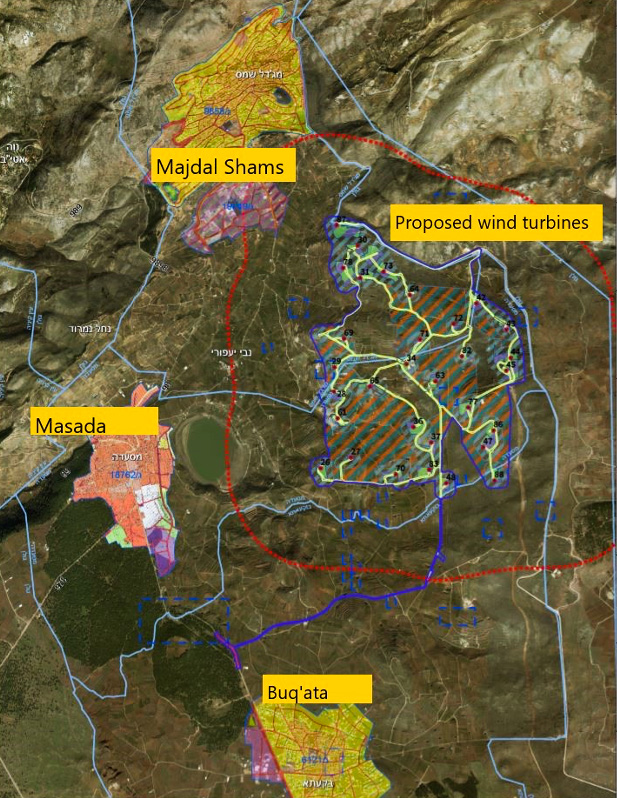

Dubbed the ARAN Wind Project, the plan will install 23 wind turbines on nearly a quarter of Syrian agricultural land. The original proposal requested 52 wind turbines, but the project was scaled back as it went through the government stages.

Energix denies the project will harm the local economy, environment, and health, arguing, “it will lead to a significant improvement in the quality of life of the residents” and “occupy less than 2 percent of the margins of the agricultural space of the Druze community.” According to the approved project map, the wind farm will span a little more than 3,500 dunams (nearly 870 acres).

A map published by Al-Marsad shows proposed turbine locations in the midst of farmland nestled between Syrian villages

Energix boasts the project will create hundreds of jobs while meeting Israel’s renewable energy goals. Israel entered the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015 and agreed to have 10 percent of its energy produced through renewable sources by 2020 and 17 percent by 2030.

But according to expert testimonies filed as part of a joint objection to the wind farm, the project will significantly harm Syrians’ health, housing, and livelihoods.

Dr. Hagit Ulanovsky, who provided an expert opinion for the community appeal, explained that because of the region’s mountainous topography, residents are going to feel the infrasound from the wind turbines more intensely in their bodies. And these noise disturbances will ultimately prevent Syrian farmers from cultivating their land.

“The noise is going to be impossible. Nobody will be able to stand 200 to 300 meters [about 650 to 980 feet] from each turbine, which is half of the area that’s covered,” Ulanovsky said. “And during the construction phase, thousands of trees will be taken out and basically be dead forever.”

“At least 500 to maybe 5,000 years of Druze people living in the same place and growing the same trees for several generations is going to stop,” Ulanovsky added.

A forgotten occupation

Israel occupied the Syrian Golan during the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. Hundreds of thousands of Syrians were forcibly displaced and now roughly 22,000 Syrians remain in the four villages of Majdal Shams, Masada, Buqata, and Ein Qiniyye. In 1981, Israel annexed the Syrian Golan and tried to impose Israeli citizenship on the Jawlani, the Syrian residents of the occupied Golan Heights. Many Jawlani continue to this day to reject Israeli citizenship, with only 20% of the population having acquired it.

Dr. Muna Dajani from the London School of Economics, who also provided expert testimony, explained that because of this refusal to take Israeli citizenship, the Jawlani’s travel documents state they don’t have a nationality. Instead, the Israeli government has labeled them as “undefined.”

“The Jawlani have started relating more and more to the land as their source of identity and their source of belonging to a community because of that exclusion from being Syrian, and that meant they started valuing the land beyond its physical economic value,” Dajani said.

“Constructing these wind turbines in the middle of the land not only undermines the economic viability of their agriculture but also has a detrimental psychological effect on their community well-being, their sense of purpose and sense of belonging,” Dajani continued. “People feel without land they have nowhere, they don’t have an identity left.”

Expert opinions also emphasized the wind farm will restrict the expansion of at least three surrounding Syrian villages, thereby exacerbating the housing crisis in these communities. The collective appeal was submitted by Al-Marsad to the NIC in June 2019 on behalf of Syrian agricultural cooperatives, civil society groups, and thousands of civilians. By August of that same year, the NIC rejected all objections and approved the project in September.

Energix plans to connect the wind farm to the electricity grid by the end of 2022. Nizar Ayoub, Al-Marsad’s director, told MintPress News that the organization is collaborating with the Association for Civil Rights in Israel and Planners for Planning Rights (Bimkom) to utilize every legal tool to stop the wind turbine project. Al-Marsad alleges the project violates international humanitarian law whereby an occupying power is prohibited from exploiting the natural resources of the occupied territory or using their land for economic benefit.

However, the organization is currently embroiled in a lawsuit against them from Energix. In 2019, the energy company sued Al-Marsad, claiming the human rights center defamed them and violated Israel’s Anti-Boycott Law. In addition to the lawsuit against Al-Marsad, Energix also filed five cases against activists.

“There’s no basis in their arguments,” Ayoub said. “They’re just using this strategy to silence the local communities and Al-Marsad.”

The resistance continues

Following this month’s confrontation between Israel police and activists, the local committee for planning and construction – Ma’ale Hermon – issued a restraining order to Energix to cease all work. The order was issued after the local village councils filed an appeal to the committee. Energix is aware of the order but said it will not impact their wind turbine project and has no legal grounds.

For activist and farmer Masood, any attempts by local authorities to stop the project are merely a sham.

“The municipality doesn’t represent Syrian Arab citizens in the Golan because they’re appointed by the Israeli authorities,” Masood said. “In this conflict, they didn’t invest a lot of effort to stop it. So, all the effort was from social, public, and private initiatives and dependent on us farmers and citizens of the four villages—not the municipalities.” The village councils weren’t available for comment.

The Syrian activists’ next steps rely on how Energix proceeds, Masood said, “if they want to force this project on us, we will react.” Activists are currently working with an engineer to measure the amount of land damage caused and submit it to their lawyer in Tel Aviv for court procedures.

“But in the field, whenever the company will come back,” Masood said. “We will stand and confront it.”