Washington has proven that it is willing to make people suffer, and even starve, if governments don’t acquiesce to normalization with Israel, writes As`ad AbuKhalil.

As`ad ABUKHALIL

The recent announcement that Washington would be lifting U.S. sanctions on Sudan in return for Sudan’s normalization with Israel is a case study of U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East.

Sudan, like Somalia, has long been a battleground for Cold War intrigues by the U.S., which is responsible for the massive export of arms to both countries. Like the longtime Somali dictator, Muhammad Siad Barre, Sudan’s Jaafar Nimeiry (1969-1985) switched sides during the Cold War, and the U.S. was more than willing to reward him.

In my childhood in the 1960s, Sudan had one of the most vibrant political cultures and media in the Arab world.

Its famous politician Muhammad Ahmad Mahjub (who served both, as prime minister and foreign minister) was the quintessential mediator in intra-Arab conflicts, and his name was dominant in Arab newscast. He was often dispatched by Egyptian leader Gamal Abdul Nasser to reconcile warring factions and feuding rulers.

Sudan had more political parties than most Arab countries, which then (and many now) prohibited political parties. (Gulf monarchies — the West’s favorite governments in the Middle East — still ban them.) Sudan’s political spectrum was rather rich, ranging from communists to Islamists, from secularists to fundamentalists. Yet, during the democratic era of Sudan in the 1960s, political parties were able to deal with their differences without war or bloodshed.

End of a Brief, Vibrant Democratic Era

But the democratic era of Sudan did not last long; it was ended when a U.S.-trained military officer, Nimeiry, launched a military coup d’etat that ended Sudan’s vibrant democracy. (American media always insisted that Israel was the Middle East’s only democracy when both, Lebanon and Sudan had democratic political systems).

Nimeiry was an eccentric figure: he was first inspired by Nasser and wanted to model his “revolution” after the Egyptian revolution of 1952. He consulted often with Nasser and pursued policies supportive of the Palestinian resistance and Arab unification.

Like Muammar Qadhdhafi of Libya, who seized power in the same year, Nimeiry wanted to impress Nasser. That pleased the Sudanese people who were — like Arabs elsewhere — swept with the tide of Arab nationalism which Nasser had inspired since his nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956. While the people of Sudan were not pleased with the squabbling and internecine wars among the various political parties represented in parliament, they did not necessarily want to replace representative democracy with a repressive military government.

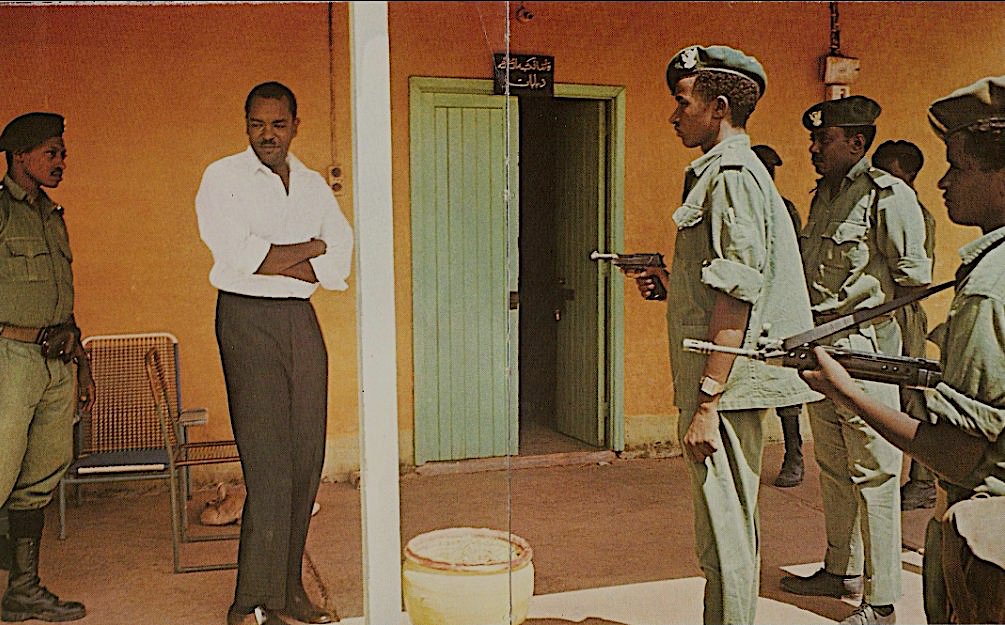

Nasser died in 1970, and military leaders in North Africa were on their own to fashion their policies and governments. There were coup attempts to replace Nimeiry but none affected him as deeply as that of 1971, when Sudanese communist officers (led by Hashim `Ata) attempted to overthrow him. He was deposed for a few days before he launched a counter-attack and restored himself to power (possibly with U.S. assistance given that the communists almost seized power).

Hashem al Atta under arrest following the failed 1971 Sudanese coup d’état. (Wikimedia Commons)

Nimeiry responded with hangings and a brutal campaign against one of the largest political parties in the Arab world at the time. Communist leaders of Sudan are still remembered for their courage while facing the gallows; the Sudanese communist leader, `Abdul-Khaliq Mahjoub, could have sought refuge in the East German embassy but he instead surrendered himself and was hanged. Communist union leader, Ash-Shafi` Ahmad Ash-Shaykh, walked to his death chanting: “Long live the struggle for the working class.”

Aligning with US

Prime Minister Gaafar Mohammad Nimeiri of Sudan, at right, arriving in U.S. for a state visit, 1983. (U.S. government, Michael Tyler, Wikimedia Commons)

Nimeiry then shifted his foreign policies away from the U.S.S.R. and aligned himself squarely with the U.S. Washington was more than happy to arm and fund another Middle East dictator who would serve U.S. efforts during the Cold War. It is still not fully known the extent to which the U.S. assisted Nimeiry in crushing the communist coup and in the crackdown against Sudanese communists that followed.

Nimeiry also moved his policies away from support of the Palestinian resistance and was one of the few Arab leaders to maintain close ties with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat even after the Camp David accords. Like other opportunist Middle East leaders, Nimeiry was suddenly overcome with religious zeal in the early 1980s and decided to impose brutal Islamic penal measures on a country known for its diversity and for its flexible version of Islamic practices.

The Sudanese people were horrified when he imposed a ban on alcohol and enacted the amputation of hands as punishment for theft (just like in Saudi Arabia, which maintained excellent relations with him). Nimeiry also ordered the execution of moderate Islamic thinker and leader, Mahmoud Mohammed Taha in 1985.

Nimeriy was overthrown in the same year, and Sudanese gathered outside local hotels, chanting: “We want beer, we want beer”, declaring an end to Nimeiyi’s fanatic prohibition and repression. The U.S. lost a close ally who rendered crucial military and intelligence services to itself and Israel, and was known for facilitating the flight of Falashas from Ethiopia to Israel for a fee.

A Singular Surrender

Nimeiry was overthrown by a military general who is still remembered as the only Arab military figure who ever surrendered power voluntarily (Gen. Muhammad Siwar Ad-Dhahab). He considered his mission to lead a transition to democratic rule, but that was not to last because another officer, Omar Al-Bashir, would seize power in 1989 and rule the country until last year.

The U.S. opposed Bashir during much of his rule and he also imposed a religiously fanatical rule, and repressed the opposition. He aligned himself with local Islamists, Iran and the Syrian regime, but toward the end of his rule — and in return for cash — he shifted his alliances toward Saudi Arabia and UAE. Both support regimes that move away from Iranian influence.

Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir during development conference Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Jan. 31, 2009. (U.S. Navy/Jesse B. Awalt, Wikimedia Commons)

Bashir also ended his support and relationships with Hamas and Hizbullah. He also is remembered for his savage role in the wars of Sudan in Dharfur and the South. But the U.S. and Israel served as midwives for the creation of the country of South Sudan in 2011, thus depriving the North of vital oil resources.

Bashir was overthrown in a military coup accompanied by a popular uprising. (It is not known if the U.S. was involved, although that is very likely as the new military junta seems to serve U.S. interests rather obediently.) The uprising pushed for civilian rule and popular elections, but the military junta (and presumably the U.S. and the Sudanese intelligence service) would not allow freedom for the people of Sudan and maneuvered for ostensible power sharing between the military junta and so-called representative of the popular uprising.

A Sudanese economist, Atallah Hamdok, with experience in Western and UN agencies, was selected as prime minister. But it quickly became clear that the generals would be running the show, leaving only technical financial matters in the hands of Hamdok and Western leading institutions. The real power was in the mitts of the chief of the intelligence service, Abdul-Fattah Al-Burhan (who was the local executioner of the Kushner-Netanyahu vision).

Sudanese protestors near the army HQ in Khartoum, April 2019. (M.Saleh, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

All this occurred in the context of Jared Kushner’s adventures in the Middle East region and his failure to sell his Deal of the Century, which was only endorsed by its real architect, Benjamin Netanyahu.

When the Deal fell through, the alternative was a quick scheme to bolster the sagging fortunes of the Trump campaign. Saudi Arabia had been pushing its own peace plan since 2002, known as The Arab Peace initiative, which basically provides Israel with full normalization in return for Israeli withdrawal from Gaza, West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Normalization in Return for Nothing

Secretary of State Michael Pompeo arrives in Khartoum, Sudan, Aug. 25, 2020. (U.S. Embassy Khartoum, Alsanosi Ali, U.S. State Department, Flickr)

But the second end of the bargain was never acceptable for Israel, and it (and Kushner) instead pushed for normalization-in-return-for-nothing.

The UAE and the Saudi client state Bahrain were more than happy to lend a helping hand to Trump, who they see as the winner on Nov. 3, due to wishful thinking. They are banking on being rewarded in a second Trump term.

Sudan is one of the poorest Arab countries and Bashir left the country’s economy in shambles. The U.S. has been imposing a series of cruel sanctions on the country.

The Sudanese new government (led by the generals who are clients of the U.S.) was basically blackmailed — literally — by the U.S. government. The government was told that to lift the U.S. sanctions, free frozen Sudanese assets and to end its designation as a terrorism-sponsoring country, it has to establish relations with Israel.

This trade-off discredits the very U.S. designation of countries on the terrorism list. (Apparently the U.S. doesn’t mind terrorists establishing relations with Israel). It underlines the use of economic livelihood and survival as a regular target of pressure and coercion by the U.S. government.

Yemen (one of the poorest Arab countries) was punished in 1990 when it voted against the U.S. wishes in the Security Council to vote for military action against Iraq. Furthermore, the U.S. wanted Sudan to pay $335 million in compensation to the families of victims of Osama Bin Laden’s terrorism during his stay in Sudan, as if the people of Sudan had a hand in it.

Rushing through the last stretch of his campaign, and eager for an achievement to brandish on the campaign trail, Trump could not wait, and an ultimatum of 24-hours was issued to the government of Sudan: either normalize with Israel or the terrorist label would stick, and sanctions would remain.

President Donald Trump in conference call with Sudanese officials and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu after Sudan agreed to start normalizing ties with Israel, Oct. 23, 2020. (White House, Tia Dufour)

The government (or the generals against the wishes for their public) obliged and made itself a hostage of U.S.-Israel relations. There were protests in the Sudan against normalization but none of the Western media reported it. Zogby analytics (which had longstanding, strong business ties with the UAE regime) published bogus public opinion polls claiming to show support for normalization with Israel, when the most comprehensive and methodologically sound survey of Arab public opinion showed yet again that normalization with Israel is widely unpopular among the Arab population (even in Gulf countries).

The precedent of what happened in Sudan bodes ill for the region. It proves that the U.S. won’t refrain from resorting to the most cruel methods to force Arab governments to establish peace with Israel. Those peace treaties will require a solid U.S. commitment to support Arab despots at all cost to preserve those treaties.

The U.S. has proven that it is willing to make people suffer, and even starve, if governments don’t acquiesce to its demands for normalization. The current Lebanese crisis, for instance, is partly due to U.S. pressure on Lebanon to improve relations with Israel and to weaken the role of Hizbullah in the political process (Hizbullah received the largest number of votes in the last parliamentary election).

The Lebanese government got the hint and quickly arranged for border negotiations with Israel under U.S. and UN auspices (the U.S. even demanded that Lebanon recognize the U.S. as an honest broker between Lebanon—a country suffering from U.S. sanctions — and Israel — the United States’ closest ally in the Middle East).

The U.S. had made similar promises to Arab countries before: in 1979 in Egypt and in 1994 in Jordan the U.S. promised prosperity and development if the two countries were to normalize relations with Israel. Decades later, the two nations still suffer from poverty and growing public debts.

It seems the U.S. formula is for Arab countries to normalize relations with Israel in return for more U.S. pressures and dictates, and for false promises of economic relief. Sudanese officials admitted to The New York Times that they were subjected to strong arm twisting by the U.S., and the Sudanese people are becoming more and more vocal against this peace announcement.

The uprising leaders are insisting that the transitional government does not have the powers to reach peace with Israel. It would not be surprising if this Sudanese-Israeli peace agreement will be as short-lived as the Lebanese-Israeli peace deal of 1983, which lasted less than a year.