Ethiopia appears to be going ahead with its vow to begin filling a crucial hydroelectric dam on the Nile River after protracted negotiations with Egypt broke down earlier this week. There are grave concerns the two nations may go to war as both water-stressed countries consider their share of the world’s longest river a matter of existential imperative.

Cairo is urging Addis Ababa for clarification after European satellite images showed water filling the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Ethiopia has stated that the higher water levels are a natural consequence of the current heavy rainy season. However, this month was designated by Addis Ababa as a deadline to begin filling the $4.6 billion dam.

Egypt has repeatedly challenged the project saying that it would deprive it of vital freshwater supplies. Egypt relies on the Nile for 90 per cent of its total supply for 100 million population. Last month foreign minister Sameh Shoukry warned the UN security council that Egypt was facing an existential threat over the dam and indicated his country was prepared to go to war to secure its vital interests.

Ethiopia also maintains that the dam – the largest in Africa when it is due to be completed in the next year – is an “existential necessity”. Large swathes of its 110 million population subsist on daily rationed supply of water. The hydroelectric facility will also generate 6,000 megawatts of power which can be used to boost the existing erratic national grid.

Ominously, on both sides the issue is fraught with national pride. Egyptians accuse Ethiopia of a high-handed approach in asserting its declared right to build the dam without due consideration of the impact on Egypt.

On the other hand, the Ethiopians view the project which began in 2011 as a matter of sovereign right to utilize a natural resource for lifting their nation out of poverty. The Blue Nile which originates in Ethiopia is the main tributary to the Nile. Ethiopians would argue that Egypt does not give away control to foreign interests over its natural resources of gas and oil.

Ethiopians also point out that Egypt’s “claims” to Nile water are rooted in colonial-era treaties negotiated with Britain which Ethiopia had no say in.

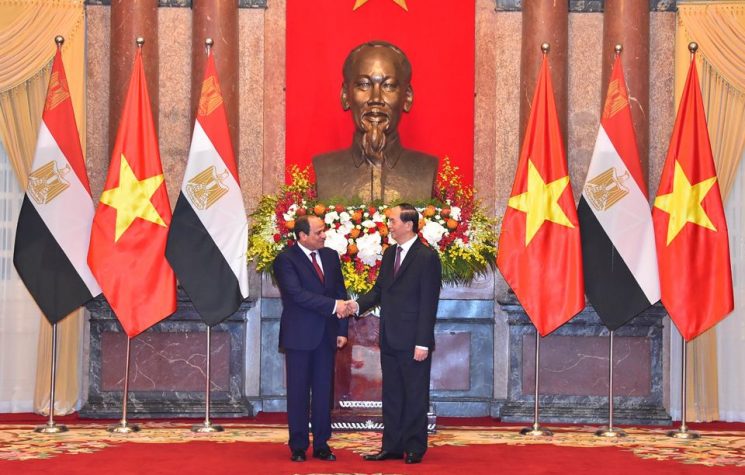

What makes the present tensions sharper is the domestic political pressures in both countries. Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi is struggling to maintain legitimacy among his own population over long-running economic problems. For a self-styled strong leader, a conflict over the dam could boost his standing among Egyptians as they rally around the flag.

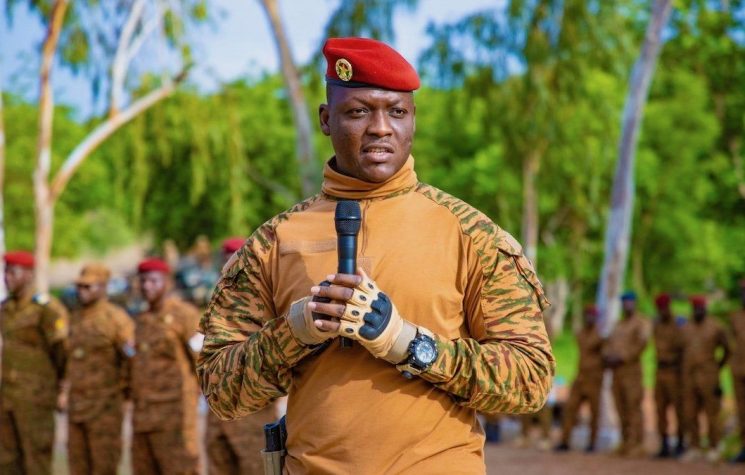

Likewise, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is beset by internal political conflicts and violent protests against his nearly two years in office. His postponement of parliamentary elections due to the coronavirus has sparked criticism of a would-be autocrat. The recent murder of a popular singer-activist which resulted in mass protests and over 100 killings by security forces has marred Abiy’s image.

In forging ahead with the dam, premier Abiy can deflect from internal turmoil and unite Ethiopians around an issue of national pride. Previously, as a new prime minister, he showed disdain towards the project, saying it would take 10 years to complete. There are indicators that Abiy may have been involved in a sinister geopolitical move along with Egypt to derail the dam’s completion. Therefore, his apparent sudden support for the project suggests a cynical move to shore up his own national standing.

Then there is the geopolitical factor of the Trump administration. Earlier this year, President Donald Trump weighed in to the Nile dispute in a way that was seen as bolstering Egypt’s claims. Much to the ire of Ethiopia, Washington warned Addis Ababa not to proceed with the dam until a legally binding accord was found with Egypt.

Thus if Egypt’s al-Sisi feels he has Trump’s backing, he may be tempted to go to war over the Nile. On paper, Egypt has a much stronger military than Ethiopia. It receives $1.4 billion a year from Washington in military aid. Al-Sisi may see Ethiopia as a softer “war option” than Libya where his forces are also being dragged into in a proxy war with Turkey.

Ethiopia, too, is an ally of Washington, but in the grand scheme of geopolitical interests, Cairo would be the preferred client for the United States. Up to now, the Trump administration has endorsed Egypt’s position over the Nile dispute. That may be enough to embolden al-Sisi to go for a showdown with Ethiopia. For Trump, being on the side of Egypt may be calculated to give his flailing Middle East policies some badly needed enthusiasm among Arab nations. Egypt has the backing of the Arab League, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Egypt has previously threatened to sabotage Ethiopia’s dam. How it would do this presents logistical problems. Egypt is separated from Ethiopia to its south by the vast territory of Sudan. Cairo has a strong air force of U.S.-supplied F-16s while Ethiopia has minimal air defenses, relying instead on a formidable infantry army.

Another foreboding sign is the uptick in visits to Cairo by Eritrean autocratic leader Isaias Afwerki. He has held two meetings with al-Sisi at the presidential palace in the Egyptian capital in as many months, the most recent being on July 6 when the two leaders again discussed “regional security” and Ethiopia’s dam. Eritrea provides a Red Sea corridor into landlocked Ethiopia which would be more advantageous to Cairo than long flights across Sudan.

Nominally, Eritrea and Ethiopia signed a peace deal in July 2018 to end nearly two decades of Cold War, for which Ethiopia’s Abiy was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. However, the Eritrean leader may be tempted to dip back into bad blood if it boosted his coffers from Arab money flowing in return for aiding Egypt.

There will be plenty of platitudinous calls for diplomacy and negotiated settlement from Washington, the African Union and the Arab League. But there is an underlying current for war that may prove unstoppable driven by two populous and thirsty nations whose leaders are badly in need of shoring up their political authority amid internal discontent.